Vegan Afelia

Ingredients

1 block tofu, pressed and cubed

2 cups (550ml) red wine

3 potatoes, sliced

1/2 cup (100ml) water

1.5 cups (160g) mushrooms, sliced

2.5 tbsp cumin

3 bay leaves

Salt

Pepper

Olive oil

Instructions

- At least one hour prior to cooking, marinate the tofu in the wine, cumin, and bay leaves, stirring to ensure everything is mixed and covered. \

- After the tofu has marinated, fry the potatoes in olive oil until brown on both sides (~3-5 minutes). Add to a soup pot, but don't raise the heat. \

- Drain the tofu, adding the marinade to the soup pot with the potatoes. Fry the tofu until lightly crispy (~5-7 minutes). Once fried, add the tofu into the soup pot. \

- Add the water to the soup pot. Raise the heat to a boil, then cover and lower to a simmer for at least half an hour. \

- After half an hour of simmering, saute the mushrooms in olive oil until soft (~3-5 minutes). Sprinkle with salt and pepper, then add to the soup. \

- Simmer for at least another half hour, then serve over bulgur or couscous.

A Longer and More Detailed Description

I love lazy recipes. I love being able to put in a small amount of effort to make something, ignore it, and then eat something delicious an unknown amount of time later. It’s also why there are so many soups in this series. Soup is the epitome of “make it and ignore it” foods.

Today’s recipe is a stew rather than a soup, but the principle still holds. This is a lazy dish, and I love it.

Start your cooking process a few hours before you’re actually hungry so you can stare at it every once in a while and let your belly consider whether or not it wants to grumble. Mix together cumin, a tragic amount of red wine, and some bay leaves, then chunk some pressed and cubed tofu into it. Let it sit and stew for at least an hour while you do other, more interesting things with your life than bathe in a red wine bath like some perverse, delicious Dionysus.

Eventually, though, you and your lazy self must add additional ingredients to the wine bath. After an hour or so of the tofu marinating, slice and fry your potatoes. Drain the wine into the potato pot, fry the tofu until it looks vaguely meaty, then add it back into its wine bacchanalia. Add the water, bring it all to a boil, then lower it to a gentle, steamy simmer. Wander off once again, and do not, under any circumstances, join said bacchanalia.

After half an hour or so of wondering what’s going on in the pot, send in the mushrooms to find out. Soften them up by sauteeing them in olive oil, add them in, and leave again, hopeful that this time, you might actually get some answers.

Finally, when you can’t take it anymore, your belly is grumbling, and it’s clear you’re ready to eat, open the lid of the pot to see what remains of your wine and tofu stew. Everything should be gloriously purple and steeped in flavour, telling nothing of what happened in the pot in the meantime. Serve over couscous or bulgur. Καλή όρεξη!

Substitutions

For the tofu: I originally thought about making this with oyster mushrooms to get a meatier flavour, but couldn’t get them to marinate properly. My partner suggested tempeh, but I’m not a fan, so I didn’t do that. Either might work for you if you’re not feeling tofu.

For the mushrooms: I used chestnut mushrooms. The sauteed mushrooms added a nice little extra bit of umami, but are not necessary, if you don’t like mushrooms.

For the wine: You can also substitute juice. I guess.

What I changed to make it vegan

Afelia is a pork stew and ordinarily marinates for hours. I substituted in tofu for the pork and adjusted my marinating expectations accordingly. It likely doesn’t quite capture the full body of flavour, but I think it still works pretty well.

What to listen to while you cook

Given the length of the cook time, I don’t recommend listening to something the entire time this is cooking, unless you’re really in the mood for music. However, for the times when I was doing something, I was listening to Methysos, and specifically Momotaro. It is well worth a listen if you enjoy folk metal.

A brief context for this dish

I initially struggled a bit to find a uniquely Cypriot dish. As might be expected, Cypriot cuisine is heavily influenced by both Greek and Turkish cuisine, with many of its dishes originating somewhere on the Mediterranean mainland. Cypriot cuisine is heavy in grilled meats and olives, with aubergines, okra, and artichokes playing leading roles. Olive oil can be found in vast quantities, and seafood provides an alternative to the meat dishes that characterise the island’s cuisine.

What’s unique about Cypriot cuisine, though, is less its cooking techniques or its core ingredients, and more what these ingredients are cooked in. Prior to the advent of refrigeration, meat needed to be preserved, which was done, by and large, by soaking it in wine. The defining flavour of meat of Cyprus has traditionally been and remains, the flavour of wine.

Fun fact! The world's oldest named wine is a Cypriot dessert wine.

Fun fact! The world's oldest named wine is a Cypriot dessert wine.

The Cypriot wine industry is an absolutely ancient wine industry. Archaeological evidence suggests that wine has been made on the island since at least 3000BCE. Archaeological digs have uncovered ancient wineries, amphorae with traces of ancient wine, and grape seeds, all dating back millennia. Shipwrecks found off the coast of Cyprus dating back to 2500BCE have been laden with amphorae full of wine, suggesting that, in addition to its cultivation on the island, Cypriot wine was being traded throughout the Mediterranean, loaded on to ships bound for Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. Cypriot wine-making techniques are documented in poetry from the 7th century BCE, and Hellenistic and Roman ruins on the island carry the story of Cypriot wine into the classical era, depicting Dionysus basking in the glory of Cypriot wine.

This is not my usual map, but it is still a map, and it brings me joy.

This is not my usual map, but it is still a map, and it brings me joy.

In the 12th century CE, Cypriot wine made its way out of the Mediterranean basin and into France, carried into western Europe by crusaders returning home from Byzantium. A Cypriot wine - Commandaria - is said to have won the world’s first ever wine-tasting contest, held by King Phillip Augustus, in the 13th century, and it continued to be popular until the 16th century and the Ottoman conquest of the island.

Wine-making suffered under Islamic rule, being subject both to taxation and the status of alcohol as haram - or forbidden - within Islam. While wine continued to be cultivated, the tradition of exporting it ended, with the wine being used primarily by the Cypriots for their own usage and for cooking and preserving meat.

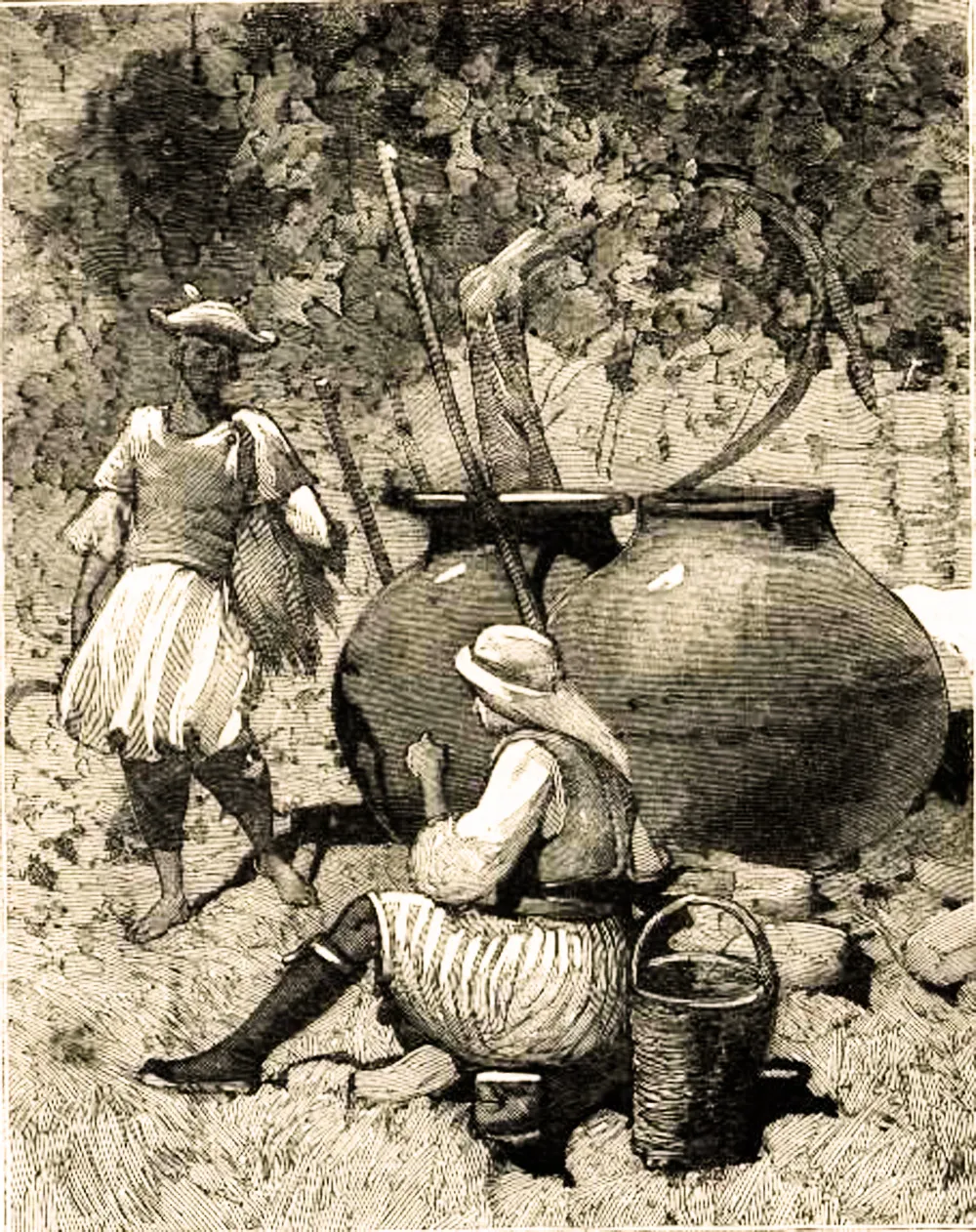

Wine jars from 1878

Wine jars from 1878

When the British took over the island from the Ottomans in 1878, the wine industry was, by and large, a cottage industry. While there were some opportunities for the wine to resume its export beyond the island, it was seen as an inferior wine, and was mostly used to fortify other, mainland wines. By the mid-20th century, the wine’s primary market was the Soviet bloc, with Cyprus exporting it as a cheap wine available to anyone. With the fall of the Soviet Union came the near collapse of the Cypriot wine industry.

In the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, the wine industry and Cypriot government faced a choice. They could let the wine die, thus ending thousands of years of tradition, or find a way to save it. The government chose to save it. The Cypriot government placed subsidies and incentives in place, encouraging the growth of small, local wineries in Cypriot villages, improving the quality of wine, and returning it to a status of a quality, delicious wine. The quality of the wine improved dramatically, and Cypriot wine continues to rise in status, returning, in some ways, to its ancient place as a home of fine wine.