Vegan Dwida Mfawra

Ingredients

20 oz (500g) vermicelli (one package)(pre-cut if possible)

16 oz (400g) chickpeas, drained

2 potatoes, diced

1 onion, minced

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 head cauliflower, chopped

2 chili peppers (optional)

4 tbsp tomato paste

3 tbsp harissa

1 tbsp turmeric

1 tbsp coriander

1 tsp ras el hanout

1 bay leaf

Salt

Pepper

Oil

Water

Kitchen equipment

Pan

Pot

Baking dish

Oven

Instructions

- Heat your oil in a pan over medium heat. Add your garlic and onion to the oil, cooking until they're translucent, about 3-5 minutes.

- Add the tomato paste, harissa, and other spices, mixing until the onions and garlic are completely covered.

- Add the potatoes, cauliflower, and chickpeas, again mixing until everything is covered.

- Add two cups of water and your bay leaf, then turn the heat down to simmer. Let simmer for thirty minutes.

- If using chili peppers, add these into your stew after thirty minutes and simmer for an additional ten minutes. Otherwise, continue to let your stew simmer for an additional ten minutes.

- While simmering, heat water in a pot and cook your vermicelli.

- Preheat the oven to 350F (180C).

- Once the vermicelli is finished cooking, add a layer of vermicelli to the bottom of your baking pan. Cover with your stew. The proportions are up to you - I had a 50/50 mix of vermicelli and stew.

- Bake for 15 minutes and serve.

A longer and more detailed description

Step-by-step instructions

First, I’m going to need you to admire that I got my ingredients picture correct this time. No weird lighting. No manky sponge. Even the kettle technically belongs to the recipe. Just look at it, and realise there’s hope for me after all.

After the very important first step of assembling our ingredients for a family photo, shove them all aside and replace them with the cutting board, a knife, and a gleeful expression as you eye your onion and garlic. Heat some oil in a pan, and chop your onion and garlic. I once again recommend trying the internet trick of pressing your garlic with the flat of a knife before peeling it to see if that helps you peel it. It’s increasingly working for me, so maybe it just takes time and patience to master. Toss them into the fire. While they are cooking, peel and chop your potatoes and cauliflower. You’re adding these once the onion and garlic are translucent (3-5 minutes), so consider whether you can peel and chop two potatoes and a cauliflower in that time as a bit of a skill test. If you can, amazing. I’m proud of you. If you can’t, I’m still proud of you. You’re still here to cook, and it’s okay if you need a bit of extra time with the cauliflower. We all do.

Once the garlic and onion are translucent, add your harissa, tomato paste, and spices, coating everything. Add your cauliflower, potatoes, and chickpeas, and coat everything again. There are some among you who might ask why I didn’t just toss the cauliflower, potatoes, and chickpeas in, then coat everything, to which I say this is my recipe, my rules, and my own forgetfulness factoring into the food. Speaking of which, add the bay leaf. I didn’t mention it before, but it does matter. Add two cups (500ml) hot water to the mix and let it simmer for thirty minutes.

While the stew is simmering, you could prep your hot chilies, if you’re using them. If you were even more responsible, you’d go ahead and cook your vermicelli for ten minutes. If, however, you are not responsible, you could wander off and get distracted during this time. You could curl up on your couch with the book you’ve been meaning to finish, only to get distracted five minutes and stare out the window. You might notice the pigeons outside, especially the one with a giant white patch on the back on his head. Stuart, you call that one, though you suspect he calls himself “Splunky the Elder” or “Lord Sexgoblin” or something like that, based on how much of a pest he is towards the lady pigeons. You see him frequently, though, and recognise him because of that white patch. Perhaps, you muse, if you paid attention, you might recognise the other pigeons too. There are occasional pigeon couples that show up, grooming each other and cuddling as they watch the rain. There are sexpest pigeons, and pigeons that just want to sit and coo. Pigeons have come to define your landscape, perhaps aware of you, perhaps not, but you are aware of them. You love them, even if you don’t know them. You cherish the time with them, even if they have no knowledge of your existence. There’s a sweet symbiosis here, or perhaps you’re a parasite. If you are a parasite, are you a harmful one? You feed them, and all you ask in return is that they be themselves, that you be able to act as a voyeur in their lives, witnessing their bliss, their struggles, their emotions -

The kitchen timer dings. Add your chili peppers to your stew, if you’re using them. Prep your vermicelli according to the package directions. Preheat your oven to 350F (180C).

Set the world from mind.

Once the vermicelli is ready, place the vermicelli in the bottom of a baking dish. Spoon the vegetable stew on top. These can be in any proportion that bring you joy, but mine was roughly 50/50 vermicelli and vegetables because that’s how the vermicelli came out of the pot what seemed most culinarily satisfying. Pop your baking dish into the oven for fifteen minutes, taking care to avoid another rabbit hole from which you will not emerge. Personally, I used these final fifteen minutes to giggle at Reddit posts and look at memes, which is the safest killing time activity known to modern man.

Remove your dish from the oven and serve. صحة وهن!ا

Substitutions and suggestions

For the cauliflower: Cauliflower is standing in for chicken or lamb in this dish. I picked it because of texture and because of cauliflower’s ability to absorb saucy flavours, which this dish has. However, if you’re not a fan of cauliflower or just want to vary this a bit, jackfruit could also work here. You could also drop any meat substitute and just add a double helping of chickpeas, if that’s more your fancy.

For the chili peppers: For this incarnation, I used habaneros, because that’s what I found at the local market (I do not know why, and will not accept any follow-up questions). However, if you want a bit of a kick without a full habanero kick, you could try jalapenos, or an even mellower pepper. I do think the peppers add a nice body of flavour to the dish, so if you can keep them, do so. However, I recommend finding one that brings you joy, rather than following my recommendations just because I made them.

For the harissa: If you cannot find harissa or do not want to buy an ingredient for a one-off recipe, I get it. Harissa is pretty great, but who knows how long it will hang out in your fridge or spice cabinet. Instead of harissa, you can use tomato paste, chili powder, and paprika. If you don’t have those ingredients, I’m going to have to ask you to reconsider following me on this project.

For the ras el hanout: This was my sneaky addition to the recipe. This is actually a Moroccan spice, not an Algerian one, so you could, in theory, drop it entirely and be fine. However, I really like what it does to the flavour, so if you don’t have access to it, consider subbing in curry powder or garam masala.

Add carrots: Several versions of this dish that I drooled at the pictures for had roasted carrots. I didn’t have carrots, so I didn’t do that, but they’d definitely be a nice choice to give this dish more body.

Using a couscous maker/double broiler: Part of my goals with these recipes is to make accessible and affordable recipes that don’t require fancy equipment or ingredients. To make this as authentically as possible, the steam from the simmering stew should be steaming the vermicelli instead of doing what I did of cooking following the package directions. If you are able to make this recipe by steaming the vermicelli, that is the better option, but just know that cooking it normally is fine too.

What I changed to make it vegan

This dish is originally made with either lamb or chicken, neither of which are vegan. Some versions are also topped with hard boiled eggs which, again, are not vegan. I dropped the eggs entirely, but substituted in the cauliflower for the meat. You could do this with jackfruit or processed meat substitutes, but I went with cauliflower because of texture, freshness, and because I know how to cook a cauliflower. I have never worked with jackfruit, and I’m too scared to start now.

A brief context for this food

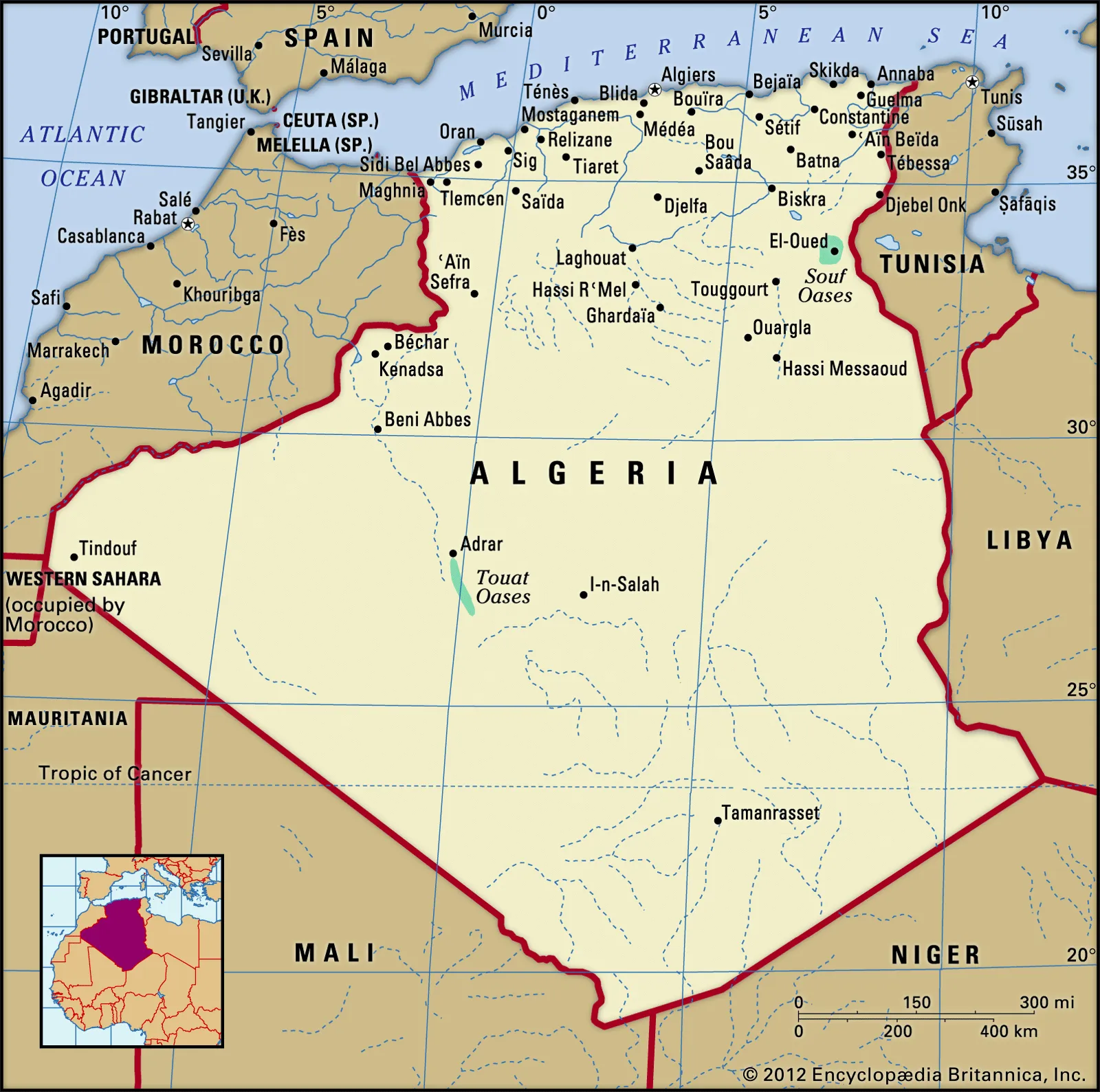

Today’s dish originates in Algeria, and, much like all the other dishes we’ve discussed, has a complex history that reflects some element of the history of Algeria itself.

Algerian cuisine, as a whole, is a unique blend of Berber, French, Arab, and Turkish cuisines, with other elements popping in and out (and which we’ll discuss when we discuss this specific dish). Algerian cuisine makes heavy use of beef, chicken, and lamb, as well as a variety of cereal grains, especially couscous. The typical image of Algerian cuisine is of couscous mixed with meat and vegetables, all cooked in a lovely olive oil. It is a tradition that reflects its Mediterranean geography, while also incorporating the unique elements of Berber heritage, and its location in North Africa.

It’s in Algerian dessert culture, however, that Algeria’s complex history shines through. Algeria has long been part of empires, from the Carthaginians, to the Romans, to the Umayyads, to the Berber dynasties, to the Ottomans. This complex history of rulers is reflected in the dessert culture of Algeria. While fruit such as watermelon and dates a common dessert, we also find Ottoman pastries. Algeria has its own unique form of baklava, as well as a variety of other pastries found throughout the modern Arab world. The Ottoman empire may have fallen, but its mark on the culinary history of the world is eternal.

When we think of al-Andalus and the long war between the Muslim and Christian rulers of Spain, Algeria was a fundamental part of that history, sharing a ruler and a fate with the caliphates of the Iberian Peninsula. Once the Reconquista finished on the Iberian Peninsula in 1492, the Spanish turned their attention to Algeria, establishing Spanish enclaves along its coast, and conquering Algerian cities, including Algiers itself. One consequence of this conquest, however, is the establishment of Algeria as a privateering hub. One particular privateer - known by Europeans as Barbarossa - became the Ottoman beylerbey (or governor) of Algeria.

It’s this multicultural, blending, chaotic environment, coupled with the impact of the Reconquista that gives rise to the dish this post is all about. While food history is generally difficult to track, I found it especially difficult to track down the history of dwida mfawra in particular. Unlike the previous recipes, there is no particular lore around it. You’ll find no Ottoman princesses languishing in their palaces, desperate for something new to eat, no imams baffled by the profligate tendencies of their new brides. It doesn’t help that most of the material I found on this dish was in either French or Arabic, languages which I do speak, but prefer not to, if I can help it. What we’re left with is what the dish itself can tell us, and the single clue I did manage to find - the dish originated in the northern city of Jijel.

Jijel is an ancient city, located near the modern border with Tunisia. Originally a Phoenician city, it was conquered and claimed by a long series of empires, including Barbarossa in the 16th century. Under Barbarossa, it, like other cities like it, became a privateering hub, where people fleeing the long arm of the law, or just seeking a safe haven could potentially find one. It remained a privateer city until it was finally captured by the French in 1839.

Algeria had, as previously mentioned, been a part of al-Andalus and the general struggle for the future of the Iberian peninsula. The rulers of Islamic Spain were also the rulers of Algeria, and as such, the same laws applied in both areas. For Sephardic Jews living in Islamic Spain and faced with the Reconquista, the coastal cities of Algeria represented a safe haven where they could continue to safely practice their faith and traditions.

Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, Sephardic Jews migrated into Algerian coastal cities, mingling with the pre-existing Jewish population to create thriving Jewish communities. Though far from the largest community, one such community existed in Jijel. There, Sephardic Jews continued practicing their traditional faith and cooking the dishes they’d brought with them from Spain.

In researching this dish, I read Jews, Food, and Spain, an excellent book by Helene Jawhara Piner. In it, she quotes an excerpt from the transcript of the Inquisition of Valencia from between 1479 and 1504. This transcript describes a range of Shabbat dishes make by Sephardic Jews that could be slow cooked so as not to break the Shabbat prohibition on working during the sabbath. One such dish - ani - is described as “something hot, usually made with fatty mea, chickpeas, beans, hard boiled eggs, and vegetables…The dish cooked all night on Friday…and stayed hot on the hearth until meal time on Saturday.” It’s a description that, while not a perfect match for dwida mfawra, starts to paint a picture of the origins of this dish.

The hallmarks of Sephardic Jewish cuisine are scattered throughout North African cuisine. Aubergines, for instance, were considered such a hallmark of Jewish cooking that the Inquisition specifically looked for their incorporation into meals as evidence that a family was still secretly practicing Judaism. While the Ottomans introduced aubergines more broadly into the region through their cuisine, Ottoman usage of aubergine and Sephardic usage are different. Algerian cuisine shows the hallmarks of both heritages, with coastal cities sometimes having Ottoman-style aubergines, and sometimes Sephardic.

This, I think, is the clue to the origins of dwida mfawra. It’s a circumstantial story, but circumstantial evidence can still paint a compelling picture. Dwida mfawra likely had its origins in Spain, specifically in the area around Valencia. As Sephardic Jews faced genocide by the Inquisition, they fled to North Africa, bringing their culinary traditions with them. For Jews in Jijel, this included the mother of dwida mfawra, a meat and vegetable stew, slow cooked in tomatoes and baked so it could be served later. From there, it, like so many other foods, blended with the local cuisine. It adopted North African harissa and vermicelli from Mediterranean merchants. It morphed and changed, becoming less a food of the Jewish community specifically, and more a food that reflected the character of Jijel itself. The name itself changed to reflect this new, Algerian identity, ceasing to be Spanish, and instead, being labelled in Arabic - dwida mfawra.

There is an irony in this narrative of the origins of dwida mfawra. Dwida mfawra is still a food to be served for special occasions, though that occasion is now Eid rather than shabbat. This is still a food that can be cooked in advance and left to warm, making it perfect for breaking the Ramadan fast. The Sephardic Jewish community itself no longer exists in Jijel, or indeed, anywhere in Algeria. Racial laws implemented as part of French occupation combined with pogroms and discrimination ensured that Algerian Jews no longer felt welcome in Algeria. After Algerian independence, many of the Jews moved to either France or Israel.

One goal I haven’t stated as part of this project, but which should be obvious from who I am and how I see the world, is that I want to try to decolonise food and explore what our relationship with food actually is. There’s the obvious element of trying to remove violence and suffering from the food itself through the use of sustainable and cruelty free ingredients, but there’s the less obvious element of choosing particular recipes and telling particular stories. When I chose to make dwida mfawra, I didn’t know anything about it, other than that its picture looked tasty, and I believed I could make it. That it’s an Eid food during Eid was a happy bonus. What I’ve found, though, is that the question of decolonising food and understanding our relationship to food is a deeply complex process. Even the question of what constitutes a “native” food is almost impossible to answer. What I feel safe saying, though, is that dwida mfawra represents a unique experience in not only Algerian history, but in human history. It is a food that survived genocide, became part of its new home, and remained, even when those who originated it were long gone. It is loved and celebrated as a product of its homeland, for it is very much a product of that homeland. It’s what happens when empire collides with genocide collides with opportunity, and it survives.

I can’t think of anything more human than that.