Vegan Mangú

Ingredients

For the mangu:

3 green plantains

2 cups (200g) mushrooms, chopped

4 tbsp vegan butter

1.5 tsp rosemary

For the pickled onions:

1 red onion, sliced into half moon rings 1/4 cup (60ml) apple cider vinegar 1 tsp salt

Instructions

- Fill a pot with water and set to boil. Peel the plantains and add to boiling water until soft (~15-20 minutes, depending on the ripeness of your plantains).\

- In a separate bowl, combine vinegar and salt, then add the onions. Set aside to pickle. \

- Heat oil in a pan over medium heat. Add your mushrooms, coat in rosemary, and saute until soft. \

- Once the plantains are soft, drain them. Mash them with a fork or masher, mixing in the butter as you do so. Add water to make them creamier, if you'd like (I added an extra 1/3 cup water). \

- Saute the red onions over medium heat until translucent (~3-5 minutes).\

- Serve with the plantains as a base, topped with the onions and mushrooms.

A longer and more detailed description

Have you ever had a morning where you were out of bread, all the bowls were dirty, and your rice cooker looked like it wasn’t feeling it this morning? It was this experience that led me to make mangu on a Thursday morning. Because you know what? When life says there are too many dirty dishes in the kitchen, the only solution is to make more.

Start by boiling water. Peel your plantains (harder than you think), chopping them into segments, and dumping them in the water. We’ll check back in on them in a little while on this breakfast odyssey. While they’re having a lovely plantain bath, chop your red onion into half moon rings, and dump it in a bowl of salt and vinegar. Your eyes will sting while you do this. It will be worth it.

It’s time for the third component of our mangu, the mushrooms! Heat some oil over medium heat, and add the mushrooms. Sprinkle them with rosemary, and saute until soft. They should even change colour, becoming darker, which always brings me joy to see.

Once the plantains are soft, drain the water, but not necessarily all of it. We’re going to be mashing and smashing those plantains, and a bit of water helps ease that process along. Mash and smash, mixing in your butter as you go, until everything is mush. Add some water if you want it creamier, or don’t if you like chunks. And really, who doesn’t like chunks?

The onions are likely done pickling at this point, so saute those in oil over medium heat. If you’re feeling really cheeky, you can use the same pan you cooked the mushrooms in. You know I did. Saute until translucent.

It’s now time for the grand finale! Combine all your components, using the mashed plantains as a base, and topping with the onions. Buen provecho!

Suggestions and Substitutions

For the queso frito: “Ah,” you say. “What’s this? Queso frito? That sounds amazing, but I didn’t see anything resembling that earlier in the recipe.” And that’s completely true. I didn’t mention this earlier, because my every attempt to make queso frito went horrifically wrong, and I ended up with a pan full of melted cheese. See, we live in this perverse, backwards world where somehow, vegan cheese has gotten good enough that it actually melts, which is unfortunate, because I was trying to just fry cheese. The cheese ordinarily used for queso frito has a very high salt content and thus a high melting point. I obviously can’t use that cheese, so I tried to find a vegan alternative, but somehow, despite all the memes, I could not find a vegan cheese that did not melt. If you manage to find one, fry it and enjoy it, and also please let know what it is, I’m weirded out at this point.

For the mushrooms: The mushrooms are standing in for salami here. Feel free to substitute whatever meat substitute brings you joy. For me, that is and always will be mushrooms.

What I changed to make it vegan

I removed the queso frito. Not by my own choice, mind you. I tried. I really tried. I really wanted to make it work, but I couldn’t. I’m endlessly disappointed.

Oh, and I subbed out salami and butter, but that’s less exciting than my failed cheese odyssey.

What to listen to while you make this

I really enjoyed Anais Martinez. She’s a bit chiller than what I generally listen to, but that works for a breakfast dish.

A bit more context for this dish

You, like me, likely looked at the word “mangu” and thought, first, that that was a fun word to say and roll around in the mouth (mangu mangu mangu mangu), and second, got curious about the etymology of the word. It has a distinctly African sound to it, but also feels in line with last week’s recipe name. So where does the name “mangu” come from?

And oh reader, this is a can of worms I am not qualified to open, but which I’m going to anyway.

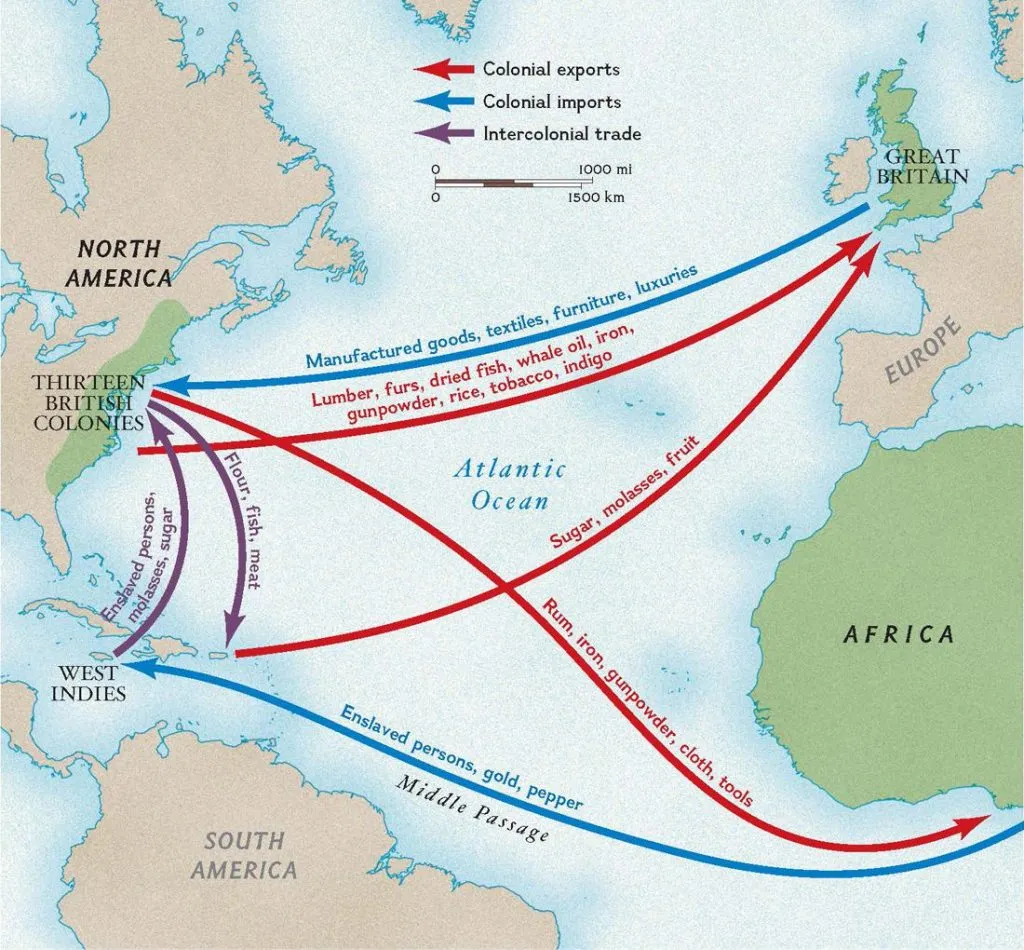

Let’s start with the map.

It's always this map.

It's always this map.

The Dominican Republic shares a similar narrative with the rest of the Caribbean. The island of Hispaniola - which is now the nations of Haiti and the Dominican Republic - was settled by Taino between the first millennium BCE and 600 CE. Their name for the island - either Ayiti or Quisqueya - may sound familiar to readers who are familiar with the area. “Ayiti,” of course, became the source of the name “Haiti.” “Quisqueya” continues to be used as a poetic term for both the Dominican Republic and Dominicans themselves. Much like with Dominica, the Indigenous identity of the Caribbean persists, despite genocide and colonisation.

Over the course of the next centuries, the island became home to a complex political system whose borders still define the modern departments of both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. When Spanish colonisers arrived in 1492, around 3 million ethnically diverse Tainos lived on the island. The Spanish founded the city of Santo Domingo, the oldest European settlement in the Americas and modern capital of the Dominican Republic. For the first few years of the colony’s existence, the Spanish lived in relative harmony with the Tainos. However, as the Spanish pushed further and further into the island’s interior, the Tainos resisted, with chiefs Anacoana, Guacanagaríx, Guamá, Hatuey, and Enriquillo leading a resistance against Spanish occupation. Though they initially won, they could not win against the disease the Spanish carried with them. By the early 1500s, 85% of the Indigenous people of the island had died of smallpox, measles, and related diseases. By 1514, that number was less than 27000. Many of the rest were enslaved through methods that, even at the time, were considered brutal and horrifying. Indeed, he was considered so brutal, he was arrested upon his arrival back in Spain.

It’s worth taking a moment here to emphasise just how horrific the arrival of Europeans was, not only for the indigenous peoples of the Americas, but globally. For starters, we do not know how many people lived in the Americas prior to the arrival of Europeans. Estimates vary dramatically, with the current scholarly consensus landing between 8 and 150 million people. By 1600, a likely 90% had died due to disease, warfare, and genocide. The amount of death was so massive, it triggered a literal ice age as land went untended and plants spread, sucking the carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A literal apocalypse rained on the Americas, and it started in what is now the Dominican Republic.

And, seeing the death around him, Columbus decided to double down on atrocity by bringing enslaved Africans to work on the now empty plantations of the newly colonised Hispaniola.

Map of the Taino chiefdoms (Source: Wikipedia)

Map of the Taino chiefdoms (Source: Wikipedia)

The first enslaved Africans arrived in Santo Domingo in 1493; however, mass importation began in 1503. By 1574, enslaved Africans outnumbered Spaniards 12 to 1. These enslaved peoples were forced to work in brutal conditions with high death rates.

However, enslaved people are rarely passive people. Hispaniola became notorious in the Spanish Empire for the sheer number of enslaved persons who escaped into the island’s mountains, becoming bandits and building a life for themselves outside Spanish enslavement. These acts of rebellion became one of the reasons Hispaniola was abandoned by the Spanish, with the population of free Africans, enslaved Africans, Taino, and Europeans intermingling and intermarrying, creating a deeply unique and diverse population.

And it’s here that I’ll get back to the mangu.

Johannes Vingboons' 100% accurate and reasonable understanding of how elevation works depiction of Santo Domingo, 1665

Johannes Vingboons' 100% accurate and reasonable understanding of how elevation works depiction of Santo Domingo, 1665

The art of boiling and mashing plantains is not unique to the Dominican Republic. The dish itself likely originated with the Africans brought to the island, and took on more of the character of what was available, much like many of the other Caribbean dishes we’ve explored in this series. It is, at its core, an African dish, brought to the Americas alongside enslaved persons, and, much like the residents of the Dominican Republic, shaped into something new and wholly its own.

The name “mangu” likely derives from the word “mangusi,” which comes from either a Congolese language, and is a generic term for a boiled and mashed tuber. Which language exactly, I couldn’t find, because that’s part of what the mass enslavement of peoples does - it jumbles languages together into something new. That “mangu” derives from “mangusi” is supported by the fact that the name is similar across the Caribbean. A similar dish is called “angu” in Costa Rica and Cuba.

Ordinarily, I would stop here, talk about how fantastic it is that ideas get transported and survive through all the horrors of genocide, and send you on your merry way. However, if I stopped here, I wouldn’t be telling you an honest story of what mangu is and represents.

If you look at sources from the Dominican Republic about the history of the dish and why it’s named “mangu,” I rarely saw this history of the name travelling with enslaved persons from the Congo. Instead, all these websites told a different story, one that cuts deeper into the heart of what mangu means in the Dominican Republic.

Et tu, Spanish Wikipedia?

Et tu, Spanish Wikipedia?

The story of the name “mangu” as described in Dominican texts goes as follows: During the US occupation of the Dominican Republic in 1916, a US soldier tried the dish of mashed plantains, queso frito, pickled onions, and salami. He sat in a cafe or restaurant or random picnic table - the stories are not clear - took a savoury bite, and contemplated it. “Man,” he said to himself. “Good.”

The Dominicans’ ears perked up around him. What was this phrase he’d said as he put their food in his mouth? Was this the English name for what they’d served him? Was this what the Americans would call it? Yes, they decided, and so, having misheard and misunderstood the phrase, the name stuck. “Man, good” became “mangu.”

This story is, of course, not true. It’s entirely possible there was an American soldier who enjoyed mangu, and there were definitely soldiers in the Dominican Republic in 1916. However, why this story isn’t true is clear on the surface. “Man, good” doesn’t sound like “mangu,” unless you have the thickest of Louisiana accents. The dish must have had a name prior to this soldier getting his hands on it. Other islands that were not lousy with Americans have similar dishes with similar names. This is not why “mangu” is called “mangu.”

Why, then, is this the story? Why this disassociation with the African roots of the dish and replacement with Americans?

There’s one more element to the story of mangu, and to understand it, let’s look at the Dominican Republic’s complex relationship with the other nation on the island of Hispaniola. Let’s look at Haiti.

The Battle of Santo Domingo (1806) by Nicholas Pocock

The Battle of Santo Domingo (1806) by Nicholas Pocock

Haiti’s story, while initially not dissimilar to the Dominican Republic’s, takes a very different turn. While I won’t go into the full history of Haiti here, Haiti was born out of a successful slave rebellion, with the Haitian Revolution in 1791 seeing the overthrow of French slave owners and the formation of an independent republic under Jean-Jacques Dessalines in 1804. The Haitian army conquered the entirety of Hispaniola, including what is now the Dominican Republic.

The Haitian Revolution is notorious for its actions against former slave owners, with revolutionaries committing multiple massacres and expropriating all land belonging both to white people and to the church. White Europeans fled Hispaniola en masse. On the Haitian side of the island, this was celebrated as a victory of the oppressed over the oppressor. The Haitian government declared anyone remaining on the island was Black, and levied massive taxes to pay off the debt it now owed to France.

For the residents of Santo Domingo, these declarations were everything they had hoped never to face. The people of Santo Domingo saw themselves as Spanish, and by extension, as white. When Haitians flooded into Santo Domingo, they encountered a people who did not want to be “liberated” from Spain. Santo Domingo rebelled almost immediately against Haiti, gaining independence in 1844, and petitioning to become a Spanish colony again in 1861. As the Dominican Republic vacillated through different governments, a common theme remained in its legislation and formation of its own cultural identity - Dominicans, above all else, were not Haitians.

And, if Haitians were going to define themselves fundamentally as Black? Dominicans would define themselves as the opposite, eschewing Blackness and defining their identities and race as anything but that.

US political cartoon by Bob Satterfield, published in 1904 in the Tacoma Times

US political cartoon by Bob Satterfield, published in 1904 in the Tacoma Times

This eschewing of identity, this is why the narrative of mangu is so complex. It’s not a case of one story being cuter than another, but rather, a case of identity itself being shaped and reshaped. Acknowledging that the story of mangu begins with the story of enslaved Africans being brought to Hispaniola and becoming part of the story of all people of the island means acknowledging that this dish is an African one, and thus represents Blackness in some way. To embrace mangu and its story for what it is is to embrace some element of a non-European identity, which, in turn, flies in the face of everything that defined Dominican identity during the Haitian occupation. This dichotomy remains within modern Dominican identity, with Dominican politics repeatedly denying the fundamental rights of anyone with even a whiff of Haitian ancestry.

But equally, that mangu is so central to Dominican identity speaks to another layer of what race, identity, and culture actually mean from a Dominican perspective. To say that Dominicans eschew Blackness is to apply to them an American - or even Haitian - definition of race that simply does not apply. Dominicans take pride in being a people of a variety of cultures and backgrounds. They apply to themselves a Dominican definition of race that is absolutely valid, and which reflects who they conceptualise themselves as, and how they define the African elements of their ancestry differently than would Americans.

And there’s something beautiful about understanding definitions other than our own, and how people conceptualise themselves. Mangu is mangu, and the narratives that are told about it say just as much about the people doing the naming as they do the food itself.