Vegan Ndole

Ingredients

1 jar (2 cups) peanut butter

3 cups (600g) spinach, roughly chopped

3 cups (750ml) vegetable broth

2 cups mushrooms, chopped

1/2 cup (80g) peas

1 onion, diced

4 cloves garlic, minced

5 small sheets seaweed, crumbled

2 tbsp ginger

1.5 tbsp miso

Instructions

-

In a large pot, bring the vegetable broth to a boil.

-

While the vegetable broth is heating, blend peanut butter, onions, garlic, and ginger until smooth.

-

Add the peanut butter mixture to the vegetable broth, stirring until smooth. Lower the heat to medium.

-

Add peas and mushrooms to the peanut butter mixture, stirring until everything is blended.

-

Add the spinach, seaweed, and miso, once again stirring until everything is blended.

-

Let simmer until the spinach is fully reduced (roughly 5 minutes), then serve.

A longer and more detailed description

Long time readers may be looking at ndole and drawing comparisons to another greens and peanut butter stew we made, our Angolan dish, kizaka. These readers may be wondering just how different another peanut butter and greens stew can be, to which I say, there is a whole world of possibilities for what to add with peanut butter and greens. Peanut butter may be a bold, dominating flavour, but it is not the only flavour of whatever dish it’s in. This is definitely a different dish.

Other readers may have the comment that the picture doesn’t look appetising. I acknowledge this comment, but would like to point out that the single continent with the most bangers has been Africa. Don’t knock it until you try it.

And try it we shall.

Start by heating up vegetable broth. Depending on how much you enjoy peanut butter, you may want to use more or less vegetable broth, as it’s going to be what waters down the peanut butter. If you want a thicker stew with a stronger peanut flavour, stick with three cups. If you want a thinner stew, add more. You could even fill your pot with broth and call it a day, if you really want to. I don’t recommend it, and you won’t be making ndole, but it’s your dinner, not mine. You can do whatever brings you joy.

While that’s heating up, we’re going to embark on the adventure of flavouring our peanut butter. Add your onions and garlic to a blender and blend them until they’re closest to whatever your blender feels like counting as “pureed.” In my case, that was small chunks, but perhaps your blender will be patient. Once your onion and garlic are “pureed,” add your peanut butter and garlic and puree again. It’s here that your blender is likely to throw a tantrum. If that’s the case, give it a stern talking to and jam the puree button down even harder. We’re making a smooth peanut butter.

Once your blender either gives up or you are satisfied that you have blended your peanut butter, add your blended mixture into your broth. Stir everything together until the peanut butter starts to dissolve into the broth, and lower the heat to medium.

It’s time to add more vegetables! Chop your mushrooms and measure your peas, and dump both into the peanut butter broth thing. Give that a lovely stir, then add your spinach, seaweed, and miso. It may look like you’re adding an absolutely massive amount of spinach, but you’re really, really not. Spinach cooks down quickly, and your spinach will vanish posthaste.

Let everything simmer. You could take this time to prepare a side (I made fried plantains on the side, which were excellent), rummage through your fridge for a Cameroonian beverage (ginger beer), or goof off on your phone. After roughly five minutes of simmering, though, everything should be ready! Glop it on a plate and proudly show it off to everyone, making sure to preface everything with “I know it doesn’t look great, but.” Enjoy, and bon appetit!

Substitutions and suggestions

For the spinach: Spinach is subbing in for bitterleaves here, which I obviously could not find because (say it with me) I live in the Netherlands. You could sub in any green here, but spinach is the closest in flavour to bitterleaves.

For the peanut butter: Instead of using a jar of pre-made peanut butter, you could also make your own, working the ingredients earlier into the process instead of blending them together at the end. For this, you would need plain peanuts, soaked for several hours, then blended, similar to how cashews can be blended to make a cream substitute. I chose not to do this, both because it’s a headache, and because I don’t like the texture of these nut blends, but also because the flavours being blended in this version of ndole aren’t as critical to add in that initial process as I think they are when this is a meat dish. However, you are welcome to blend your own peanuts if you’d like, and I hope you enjoy it.

For the seaweed: You don’t have to add seaweed if you don’t like it or don’t have it available. I still have a ton of it left from our Cambodian recipe, though, so expect to see it more often. :D

For the mushrooms: I used white and chestnut mushrooms. You are welcome to use whatever mushrooms bring you joy.

What I changed to make it vegan

Oh boy. Ndole is a seafood, spinach, and peanut stew. I took out the seafood, replacing it with miso, seaweed, and mushrooms, and replaced all the meat flavouring in the peanuts with peanut butter itself. It’s definitely different, and I’m happy to accept that it’s probably not an accurate replacement for true ndole, but it is tasty, and I did enjoy making it.

Recommended listening while cooking

I’m adding a new section because I had such a great time vibing to Cameroonian music while cooking. I really enjoyed “C’est La Vie” by Henri Dikongue as a nice way to set the mood for this dish.

A brief context for this food

Cameroon is one of the most ethnically and linguistically diverse countries in Africa, and, unsurprisingly, this reflects in its cuisine as well. Cameroonian cuisine is incredibly diverse, using ingredients from North, Southern, West, and Central Africa, as well as incorporating elements of German, French, and British cuisine. Cameroon lies in the heart of African trade routes, and both its population and its cuisine reflect that diversity.

A Portolan chart of 15th century trans-Saharan trade routes (Source: Getty images)

A Portolan chart of 15th century trans-Saharan trade routes (Source: Getty images)

Ndole draws its ingredients specifically from west and central Africa, with bitterleaf (or ndoleh) being native to eastern Nigeria and northern Cameroon, though found throughout equatorial African cuisine. The shrimp and seafood, of course, derive from the Gulf of Guinea, just off the coast of Cameroon.

The peanuts, though? While we think of peanuts as a core part of modern central and west African cuisine, peanuts themselves are not native to Africa.

You knew it was coming.

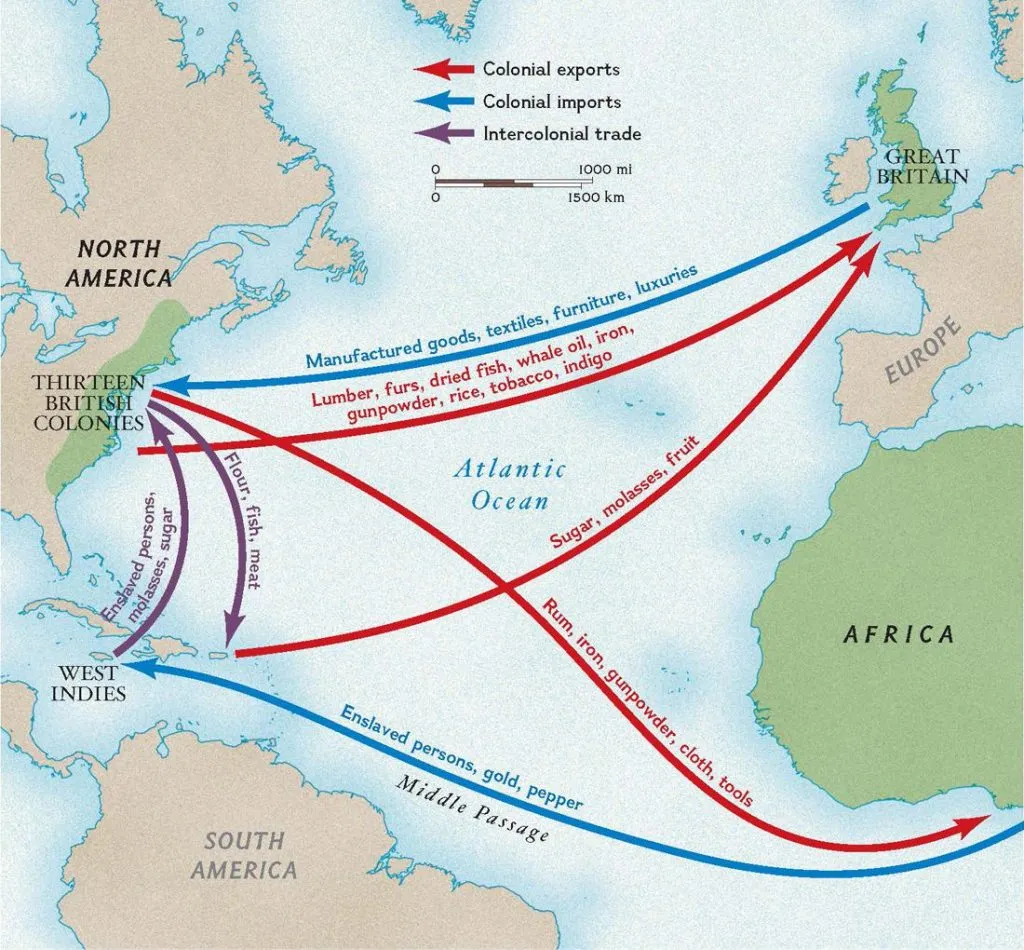

Every time I post this map, a historian gets their wings. (Source: National Geographic)

Every time I post this map, a historian gets their wings. (Source: National Geographic)

Peanuts are, like most of the ingredients we discuss in this series, native to the Americas, and were brought into Africa via the Columbian Exchange. Interestingly, the question of where specifically in South America peanuts are from is unclear. The common theory was that they originated in southern Bolivia and northern Argentina, after which they spread via South American trade routes throughout South America. However, recent studies have shown the modern peanut might have originally been cultivated in Peru, and then permeated out to the rest of South America from there. It’s unclear where the peanut comes from, essentially, but it’s clearly from somewhere in South America.

Map of one possible distribution path of maize, demonstrating pre-Columbian trade routes and movement patterns (Source: Genetic diversity and population structure of native maize populations in Latin America and the Caribbean by Claudia Bedoya)

Map of one possible distribution path of maize, demonstrating pre-Columbian trade routes and movement patterns (Source: Genetic diversity and population structure of native maize populations in Latin America and the Caribbean by Claudia Bedoya)

Peanuts are also some of the oldest food crops in South America, being part of the human story since at least 5500 BCE. There, they became part of Andean ritual cuisine, becoming associated with the cycle of death and rebirth, especially for the Viruñero of northern Peru, and in Moche art.

Moche burial art depicting peanuts and gourds (Source: Peanuts and Power in the Andes by Lindi Masur)

Moche burial art depicting peanuts and gourds (Source: Peanuts and Power in the Andes by Lindi Masur)

While we don’t know exactly how the peanut was prepared in South and Mesoamerican kitchens, we do get some clues from what the Spanish recorded after their conquest of the Incas. In the early 1500s, Garcilaso de la Vega wrote about the peanut (called “ynchic” in Quechua):

“If the ynchic is eaten raw, it causes a headache, but when toasted, is wholesome, and is very good with treacle; and they make an excellent sweetmeat from it. They also obtain an oil from the ynchic which is good for many diseases.”

Some of those uses sound familiar, and I fully admit that I am deeply intrigued by the idea of a peanut sweetmeat.

The Spanish did not solely encounter the peanut in Peru, finding different species of peanut throughout the America. Writing about the peanut (“mani” in Arawak) in the Caribbean in 1535, Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes described it as:

“…a very common crop in their gardens and fields…It has a very mediocre taste and little substance. Its consumption by the Indians is very common. It is abundant on this and other islands.”

By the time the Spanish arrived, the peanut was widespread throughout the Americas, having different meanings and value to each group of people, and being part of the Indigenous culinary landscape.

Peanuts, like many New World crops, spread into the rest of the world through Spanish conquistadors initially bringing the plant back to Spain. There, it was - and still is - grown near Valencia, before traveling along European trade routes into the rest of the Old World. However, the introduction into Africa specifically may have occurred, not due to the Spanish, but rather, the Portuguese. While there is no definitive record outlining the history of the introduction of the peanut into Africa and southeast Asia, records do indicate that it first arrived along Portuguese trade routes, including the Malabar Coast of India. The peanut also crossed the Pacific on Spanish galleons, bound for Manila from Acapulco, and being introduced into China, Japan, and Indonesia from there. It, like chilies, has a wide variety of paths it could have taken to get to my plate today, but all of them start in the Americas.

I think half the recipes in this series could cite this map as well. (Source: Springer)

I think half the recipes in this series could cite this map as well. (Source: Springer)

Upon its arrival in Africa, the peanut was grown alongside a native staple - likely the Bambara groundnut - filling in similar spaces in that culinary niche. It then made its way into the United States via the slave trade, brought aboard as a way to feed captive passengers, and grown in the United States, first in the fields of enslaved persons, and then grown more commercially as animal feed. Peanut butter itself wasn’t developed until 1890, though ground versions of the nut likely existed for as long as the nut itself has been in Africa, and the Aztecs had their own version of peanut butter.

It’s a bit ethnocentric to ascribe the popularisation of the peanut to George Washington Carver, though this history of the peanut also feels incomplete without that mention. That I list peanut butter as an easily accessible alternative to ground peanuts is attributable to Carver and his tireless work to promote both peanuts and sweet potatoes as more accessible crops for impoverished farmers. While the popularisation of peanuts extends well beyond his work at the turn of the 20th century, that I can buy peanut butter is entirely thanks to him.

Cameroon is, in many ways, defined by its diversity and its long history of being at the crossroads of Africa. That the peanut is a part of its national cuisine is another facet of that diversity. The delicious meal we made today is attributable to thousands of years of human innovation, and the willingness of that same species to learn, try, and make something new. It’s the perfect image of who we are as a species, captured in one little plant.