Apocalipsis

When designing a game, what should be at the forefront? What element of the game do you prioritise? There are some games that clearly put their stories first, and make decisions about game design to fit the story they’re trying to tell. Walking simulators are a good example of this, though far from the only example. Some games put their mechanics first, then design the entire game around that mechanic. Baba is You is a good example of this, as are, I’d argue, most puzzle games. There are, of course, many games that do both, with elements of their story fitting a particular mechanic, and mechanics being tweaked to fit the story being told. The vast majority of games, though, I suspect put either their story or their mechanics at the forefront of their design conversations, or some combination of the two.

All this is to say that Apocalipsis is not one of those games. Apocalipsis prioritised its art and music, and that reflects in the end product.

Tag yourself. I’m “dramatically draping over the edge.”

Tag yourself. I’m “dramatically draping over the edge.”

Apocalipsis is a point and click adventure following the journey of Harry as he seeks to rescue his love, Zula, from the afterlife. Like any point and click, you progress in the game by collecting items and solving puzzles. I’ve reviewed several point and clicks at this point, and though the actual mechanics of them are fairly straightforward, the twists they choose to put on those mechanics are where the game truly has an opportunity to show itself off. Some choose to invest in their puzzles, others their story, and still others in an engaging and interactive world. Apocalipsis does none of this. While it occasionally has spats of the moon logic mechanics that plague the genre, its puzzles are, for the most part, incredibly straightforward and simple. There were only a times that I had to pause to consider what to do, and then, it wasn’t because I didn’t understand the outcome, but because I didn’t understand what steps the game wanted me to take to get there.

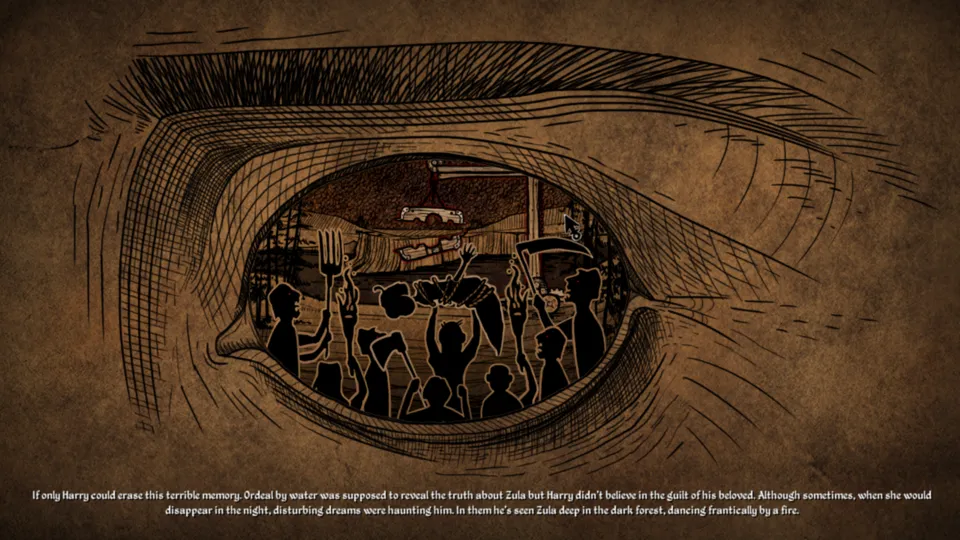

Equally, Apocalipsis’ story is thin. It is less a compelling narrative of two lovers, and more an excuse to move Harry from one set to the next. Indeed, even with as short as the game is - it clocks in at around an hour and a half - the story still manages to have plot holes. While there is a compelling story to be told about the lengths one lover will go to to save another, this is not that story. Harry faces no particular obstacles, nor does the environment he interacts with create any sense of danger. His expression rarely changes, and he rarely reacts to much of anything. He acts without any particular thought, just moving through the world as his destiny is guided by someone else. While I try not to draw comparisons, Black Book provides an excellent example of how a story like this could be told in a compelling way, with character development and obstacles along the way.

“WAP” is not an appropriate song to have stuck in your head at any point during this game. For the record.

“WAP” is not an appropriate song to have stuck in your head at any point during this game. For the record.

The story, though, is not the point of Apocalipsis, nor are the puzzle mechanics. Instead, the game feels like a vehicle by which the creators can show off their art, and where the band they have providing the soundtrack - Behemoth - can show off their music. There’s nothing inherently wrong with having a game that exists to show off its art or graphics, or even its music. I’d argue a large part of Abzu does exactly that. However, there still needs to be a compelling vehicle to carry the player from one artistic set piece to the next. There has to be some motivation to continue, whether that be the art itself or the gameplay. Apocalipsis’ art is solid. It’s not my favourite art design, but it is a loving recreation of medieval woodblock art, and provides a compelling background for the action. It reflects the philosophy of the game, and the ideas of life of death found repeated throughout the works of Hieronymus Bosch and his contemporaries. Apocalipsis bills itself on its art, and it isn’t wrong to do so. While I felt it got tedious and made less use of its source material than it could have, that doesn’t make what does exist less well done.

Apocalipsis also banks heavily on its soundtrack, and it’s here that I’m left to wonder what the intention behind this game was. Both the narration and soundtrack are done by Behemoth and its frontman, Nergal. However, both are underwhelming, with the narration being stilted, and the music quickly forgotten. All this leaves is the art, which again, while initially beautiful, gets tedious.

My dude, your lover is a witch.

My dude, your lover is a witch.

What, then, is the point of playing this game? The story is shallow, as is its exploration of medieval philosophy. The gameplay itself is simple and more of a chore than a compelling reason to continue. The music is forgettable, and the art eventually loses its unique veneer. Why play this game?

In thinking about this, I thought about what point and clicks do more generally. Point and clicks as a genre arose out of a need for efficiency in game design, and in wanting to create an interactive, visual world, while recognising the technical limitations in doing so. It was the increasing ability of technology to change how a world could be made interactive that led to their demise as a genre, and nostalgia that has brought them back. Within the point and click revival, however, each of the new games has been forced to make itself compelling in some way. They are required to build a world that the player wants to explore, or to toy with the genre’s rules, or to build sufficiently intricate puzzles that the thrill of solving them is enough to motivate the player.

Apocalipsis doesn’t do these things or, to be more specific, doesn’t do so successfully. While it understands the conventions of the genre, it understands the convention of the genre before its current renaissance. It is building a game that fits in an era that no longer exists.

It is, quite simply, medieval.

That is an appropriate face to make at that pun.

That is an appropriate face to make at that pun.

Apocalipsis isn’t a failure. I believe its developers set out to make a game that was a vehicle for its art style and music, and it does succeed at showing both of them off. Instead, Apocalipsis fails as a game, and especially as a modern point and click adventure. Its plot is too shallow to be engaging, and its puzzles are too simple to be stimulating. This is a game that needs the player to fall in love with its art and music, and if the player can’t, there’s no further reason to engage with it. There are clearly those for whom the art style works, and there are also likely those who love the soundtrack. I am not one of those players. Instead, I dragged myself through the narrative, doing my best to muster up enthusiasm, but ultimately, making roughly the same face as Harry the whole way through.

Developer: Punch Punk Games

Genre: Point And Click

Year: 2018

Country: Poland

Language: English

Play Time: 1.5 - 2 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/cGmvvQSp0wE