Beholder 2

It’s interesting how many games seek to humanise evil, or at least, put humanity in institutions that we now recognise as being rights violations incarnate. I’ve affectionately referred to Rimworld as “everyone’s favourite war crimes simulator,” and there’s some truth to that, but Rimworld represents a different kind of humanisation of evil than Beholder or its sequel, Beholder 2. Beholder told the story of a Stasi informant and his interactions with those he was informing on. It put a human face on the Stasi, not dissimilar to Der Lebens des Anderns. It was effective at its humanisation, explaining not only why the main character was an informant, but the choices he faced along the way.

Beholder 2 sets out to do something similar. Instead of a Stasi informant, you play as a bureaucrat in the governmental machine, trying to solve the mystery of his father’s death. Rather than humanising a particular version of evil, Beholder 2 puts faces on an entire system, forcing the player to re-examine their ideas of what these bureaucracies are actually built on. It’s still a version of putting the player in a position of evil and asking them to make decisions from that perspective. It leads me to the question once again of why we have this fascination with understanding evil and placing ourselves in these positions.

Oh, we’re jumping straight in.

Oh, we’re jumping straight in.

Beholder 2, unlike its predecessor, is not a management game. It is instead a 3D point and click. You play as Evan Redgrave, an entry level employee at the Ministry, given the job after the death of your father. Your goal is to solve the mystery of your father’s death, and to do so, you must rise through the ranks at the Ministry. You must get promoted into the upper echelons of the bureaucracy, whatever the cost.

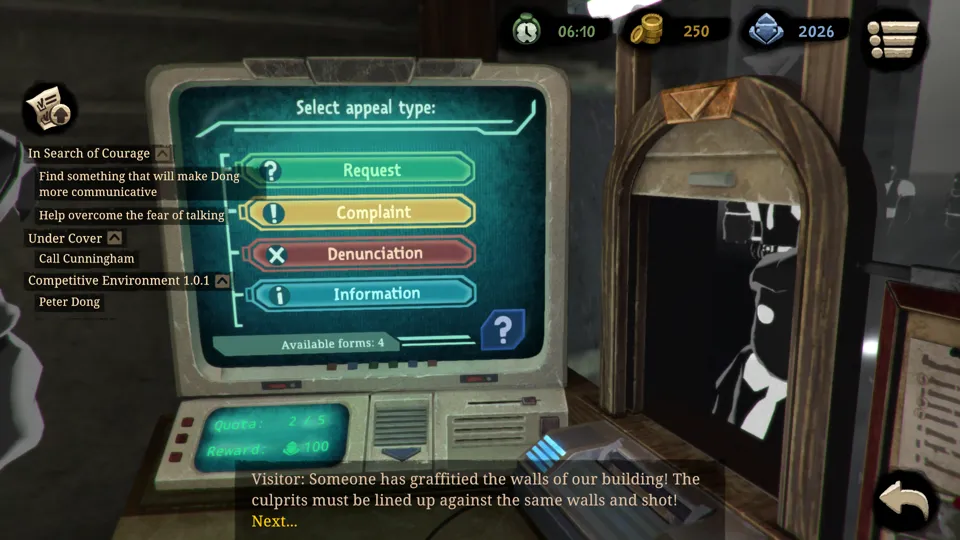

As part of this rise to power, the player receives various tasks they can do alongside their actual job. These can range from helpful and reasonable, to the absolutely deranged. It is up to the player to choose how to progress through these quests, though ultimately, that end goal of promotion remains the same.

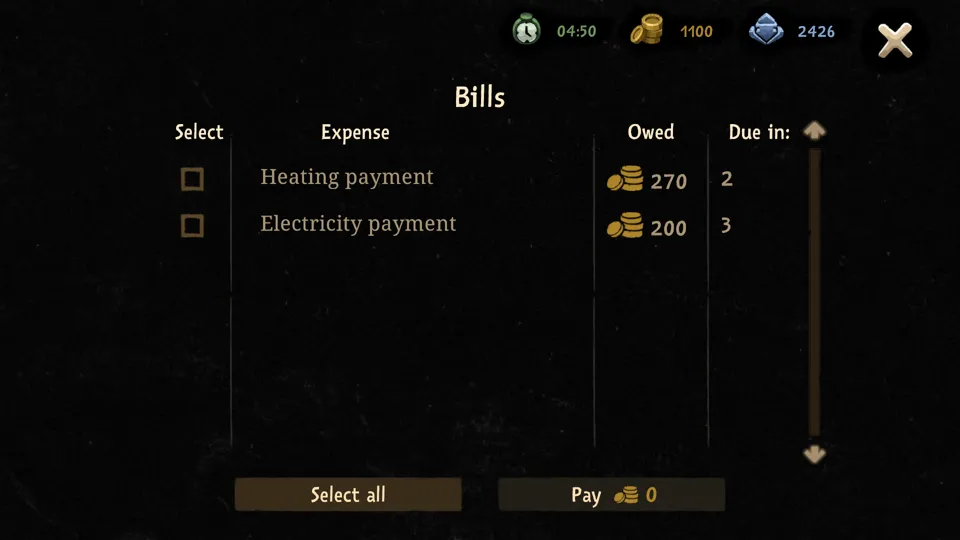

As part of these quests, the game uses three currencies - time, money, and influence. Influence and money can often be spent interchangeably - though only money can be used for the ever-increasing number of bills, and only influence can be used for a promotion or to open new conversation options - but time is a unique currency. Each day has nine hours, and each task takes a certain amount of time. The game becomes a balancing act of trying to accomplish what needs to be done, while also being cognizant of the amount of time each of the necessary tasks takes. It’s an interesting mechanic, even if it’s not a unique one, and it adds a nice bit of pressure to the game.

Oh, and Evan has a job that is reminiscent of Papers, Please, but the player doesn’t actually have to do this job with any kind of consistency. This is a bureaucracy game, not a job sim.

I may have done my actual job more than the game expected me to.

I may have done my actual job more than the game expected me to.

The goal of the game, as I said, is to get promoted into the upper echelons of the Ministry. This becomes Evan’s primary goal, and he is prepared to do so at any cost. It’s this drive that leads me to think about Beholder 2’s goals as an evil simulator. To get ahead, Evan can do casually evil things like bully a coworker, or can do more malicious things, like get a coworker executed. Evan, as the player insert, never expresses remorse for his actions, nor any clear emotional understanding of the consequences of his actions. He just does things, and it’s up to the player to decide what path Evan will take or how they themselves will feel about it.

For my part, I tried to take the most gentle path possible at every turn. Rather than driving people to suicide, I tried to help them with their problems so they would be in my debt and step out of the way of a promotion voluntarily. When I accidentally got someone executed, then, I felt bad, even though I was moving forward in my goal. While Beholder made it clear that the actions the informant was taking would lead to very bad consequences for those he was informing on, Beholder 2 is more visceral with the consequences. The player sees the heads roll - literally, in some cases - and is faced with the reality of the violence they’re committing in the name of their own goals.

Please ignore the detonator quest. I promise I’m very nice.

Please ignore the detonator quest. I promise I’m very nice.

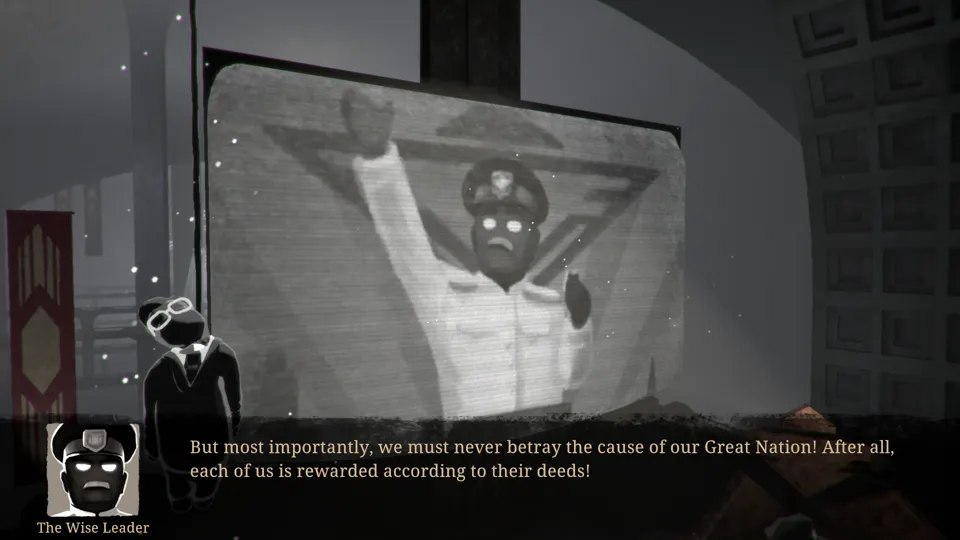

The first Beholder felt like a simulation of the Stasi, and in doing so, was interesting in its attempt to humanise a group that had made life hellish for millions of people. Beholder 2, while it has its roots in dictatorial bureaucracy, feels less like anything real, and more like a parody. It evokes Terry Gilliam’s Brazil more than any actual world, instead being a caricature of a bureaucratic hellscape and the cutthroat politics that happen just behind the scenes.

It’s after noticing that this is a caricature that the game loses some of its power. This isn’t the story of one of the faceless bureaucrats trying to do their best in a fundamentally unjust world. It’s the story of a faceless bureaucrat intentionally making that world more unjust to suit his own selfish ends. However reluctant a participant he might be, he is still a willing one who willingly engages with the system to perpetrate evil on those around him. It’s not a matter of his or his family’s survival - he does these things to enact a sort of justice, or at least with the hope that that’s what might be waiting at the end of a long thread of atrocities.

Maybe a dystopia isn’t that different from our reality.

Maybe a dystopia isn’t that different from our reality.

It’s here that I get back to that question of why we put ourselves in the role of evil. In Beholder, that reason is clear - we’re gaining a deeper understanding of the evil of the system rather than the evil of the individuals caught within it. With Rimworld, the argument is ostensibly survival, though I’d argue it’s more that Rimworld minimally humanises its NPCs, making them seem like as much objects as a tree or a fence or a cow, and thus, removes the idea that we are perpetrating evil.

With Beholder 2, though, we meet the people we are perpetrating evil against. They’re well-characterised and human, and even though they’re as much a caricature as anything else in this world, they are human by the rules the world presents. The things we do to them, then, we do to “actual” people. As much as the game argues these are necessary evils to move the game forward, when the main character’s ultimate goal is a selfish one, it’s worth asking how necessary any of the evil is when we could just as easily choose not to engage in the first place.

Beholder 2 has us taking on the role of evil ostensibly to further humanise the bureaucracy of dictatorships, but I’d argue it doesn’t succeed at that goal. Instead, Beholder 2 puts us in the role of a person who asks us to make the world worse, even within that bureaucracy, and to sympathise with him as he does so. In some ways, I sympathise with Evan, don’t get me wrong. I understand his fear, and I hope he keeps his lovely apartment. I don’t sympathise with his motivations or the actions he takes, though. I don’t see his evil as justified or as humanised. He is a sociopath, and would have had to be one from the start to engage with this system. The game might want me to believe he becomes a sociopath as a result of the decisions he’s forced into, but these are decisions he makes on the way to an ultimately unforced goal.

Beholder 2 is a perfectly decent game, though it lacks much of the tragic charm of its predecessor. It benefits from its point and click structure, and is one of the best executions of that genre I’ve seen. It has an interesting story and world, and I enjoyed playing it. I can’t shake the question, though, of the choices it makes, and what those choices say about the player. Why do we put ourselves in the position of evil, if not to give ourselves the lightest of tastes?

Developer: Warm Lamp Games

Genre: Point And Click

Year: 2018

Country: Russia

Language: English

Play Time: 12 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/Pu_DJb3jpsg