Breakout 13

I play a lot of interactive fiction. I complain about some of it, thoroughly enjoy others, but rarely do I struggle to find the motivation to finish. I always want to know where the story is going, and what it’s all been building towards.

Sometimes, it’s helpful to play a really poor narrative adventure to better appreciate the good ones, y’know?

/sobbing

/sobbing

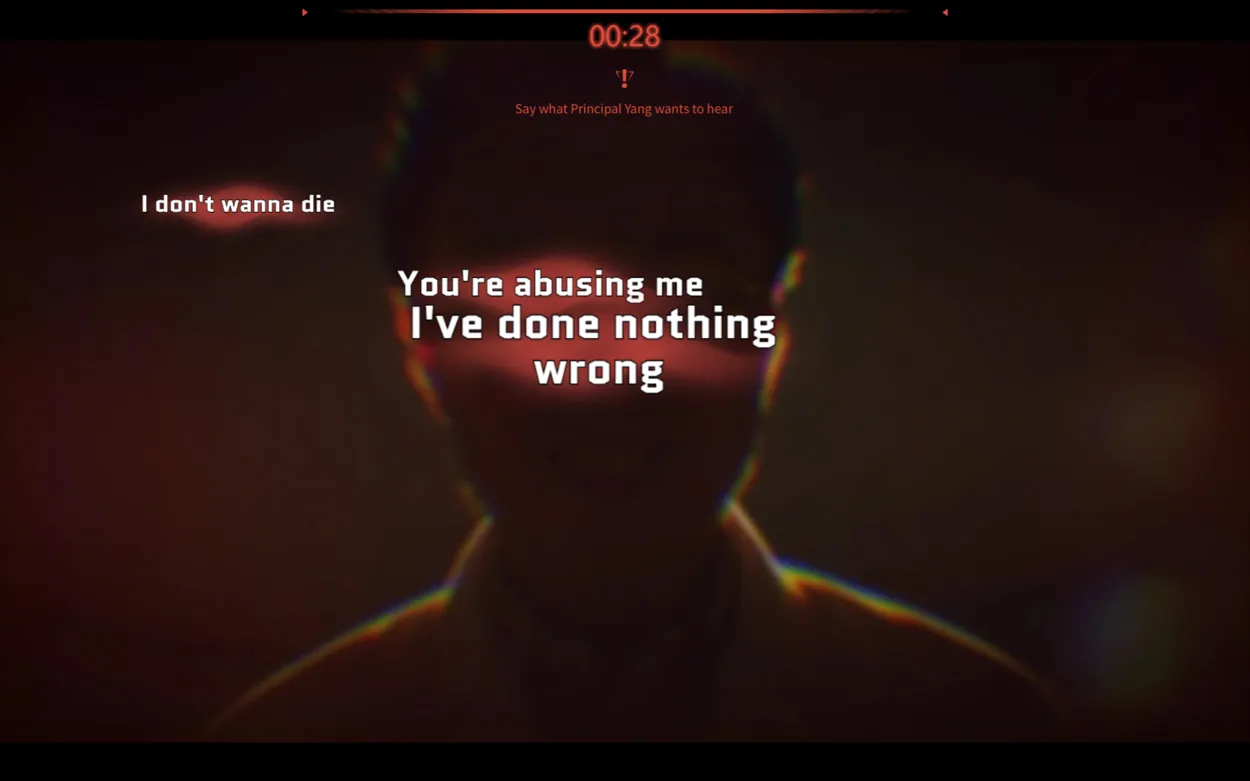

Breakout 13 is a narrative adventure game - and, more specifically, an FMV - that follows the story of Zhang Yang, a teenage boy who gets sent to a reform school somewhere in southeast Asia after getting expelled from high school for playing too many video games. Upon his arrival there, he faces torture and degradation, and immediately resolves to escape.

From the outset, this seems like a good premise for a game, and to be clear, it is. As an FMV, it’s fairly well done. The acting, cinematography, and scoring are all reminiscent of C-dramas, but that’s all completely reasonable, and a nice change of pace from other, much clunkier FMVs I’ve played . It, like every other narrative adventure, plays heavily into the idea that the player’s choices shape the narrative, with frequent points where the player has to choose between various ways of responding to the situation.

What it lacks, though, is any comprehension of what an FMV is supposed to be beyond those things, or indeed, how to even implement them in an effective or interesting way. That, and a non-paywalled ending.

I am a teenage boy. This is not a choice, but an inevitability.

I am a teenage boy. This is not a choice, but an inevitability.

Breakout 13, for all the promise of its premise, doesn’t have a narrative so much as a long sequence of things that happen. There is a clear and contained first half, where the protagonist plans, implements, and succeeds in escaping, and a second half, where he does much the same thing again, only now while investigating his fellow students for half-baked reasons. More than anything, this game feels like the developers had sticky notes on a storyboard for two different games, couldn’t decide which they preferred, then smashed them together in the hopes they would make a good game.

It isn’t. What results is a mess of odd gameplay mechanics, a needlessly bloated plot, and mishmashed character development. Indeed, if the entire first half of the game were cut, the game would be better off for it. Perhaps then, the devs also would have been able to actually add an ending to the game, instead of having it fizzle and break, insisting that the player buy a DLC if they want to know how the game ends.

This is the nice girl, and thus, the love interest.

This is the nice girl, and thus, the love interest.

All of these criticisms may seem harsh, but they’re also not out of line with what the game itself is doing with its narrative and how it chooses to present it. Like all narrative adventures, it presents itself as a bastion of player choice. In reality, however, the game has correct, likely opaque answers at every turn, with the paths deviating from that correct answer leading to immediate and dismal endings.

As one example, I got to a point where I was investigating my fellow prisoners. I had the choice of being an ass about it, or being polite but firm. I, not being an ass, chose polite but firm, going through the investigation, and finding what the game wanted me to find. I thought I had done everything right, but when I got to the conclusion, I received a game over. I tried the scene again, this time being a bit of an ass, but not a complete ass. Again, I got a game over. It wasn’t until I went through, breaking the character I’d built and being a complete ass that the game would let me progress.

Putting a game over after a player choice does not make a game respectful of player choices. What it does is set the player on a narrative railroad, where there are brief scenic viewpoints, but no true exits until the end. Except, in this case, the game doesn’t have an ending, so you’re stuck on the railroad until it careens into a wall.

These are shockingly good prison cells, by the way. Top notch.

These are shockingly good prison cells, by the way. Top notch.

I mentioned, though, that I retried that interaction several times to figure out what the game needed from me to progress, and it’s here again that the game fundamentally does not understand how to craft a narrative that actually respects and reflects player choice. Throughout, players have the opportunity to open up their storyline and replay any moment to select a different outcome. The game will show which moments have different outcomes, which lead to the same outcome, and where the player might have missed a story beat. While this can help for completionists, for someone playing a game for the story like I am, all this demonstrates is the illusion of choice and the illusion that any decision I make matters. When every choice can be immediately redone, there is no tension in whether I’m making the right choice at all. If it feels like I didn’t, or becomes clear I didn’t, I can immediately undo it. I am, essentially, save scumming the story, turning it from a narrative tapestry into the vaguest threads of what might have been a story.

And when the game just ends if I choose what I feel makes sense for the story and characters I’ve created, there is no choice but to use this system. It renders the story hollow, and thus, the entire game pointless.

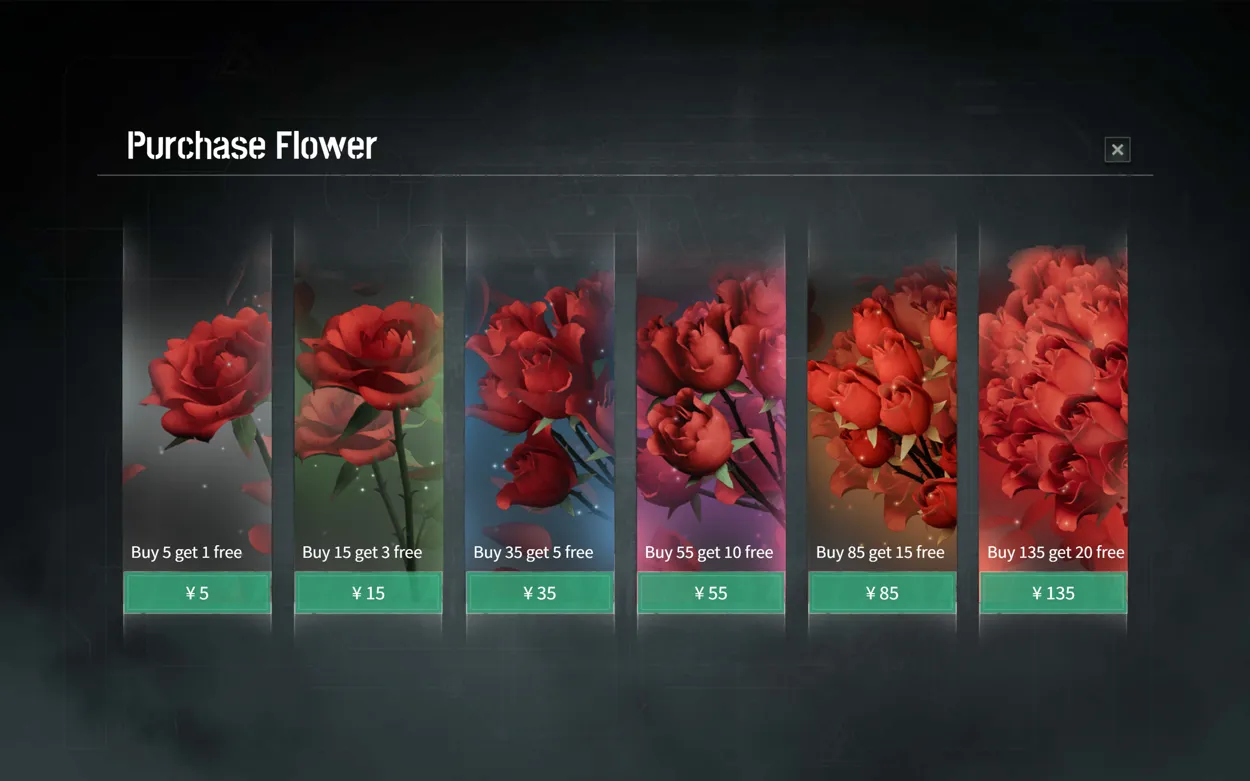

Oh, I hadn’t forgotten the microtransactions, don’t worry.

Oh, I hadn’t forgotten the microtransactions, don’t worry.

The most insulting element of this game, though, might be that it introduced microtransactions and pay to win into a narrative adventure. Throughout, Zhang Yang can attempt to curry favour with the various characters he meets, making friends or enemies, and then using these connections to open new doors and opportunities. These friendships can be curried through the choices the player makes, or the player can just buy items from the in-game, actual money shop to artificially boost these relationships.

This feels so gross and predatory that I can’t really think of any other way to describe it. The game’s ending is paywalled behind an additional DLC. The game’s very core mechanic of building relationships and earning trust can be purchased. The story feels less like a story to be engaged in on its merits, and more like a trap to engage the player so they’ll shell out extra money to see how everything ends. It is gross. It is predatory. It is bad.

i am actually running out of descriptive screenshots, that’s how much i have to say about this game

i am actually running out of descriptive screenshots, that’s how much i have to say about this game

There is an irony to all of this, of course. The game centres around the story of an unethical “doctor” exploiting parents’ fears about their children for his own sadism and financial gains. While making a bad game is a far, far cry from literal child torture, there is nonetheless an undeniable irony in the idea that a game exposing a predatory practice is itself predatory in how it chooses to tell its story. Yes, I understand indie game devs need to make money and recoup the cost of development, but it’s worth remembering there are thousands of narrative adventures out there that don’t feel the need to paywall their ending or microtransaction their content to do so.

The true tragedy is that there is a good game in here, buried somewhere beneath the lack of understanding of game design and predatory game practices. There is a good story to be told here, about exploitation, torture, and standing up in the face of adversity. This is not that game. This is a poor excuse for an FMV that, despite its excellent production values, has no real idea of what story it’s telling, or how to tell it.

Developer: Alt Lab

Genre: Fmv

Year: 2023

Country: China

Language: Mandarin

Play Time: 3-4 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/W2iwYaZa6UQ