Bunker

FMVs are video games in every sense of the word. If walking simulators and games like Before Your Eyes are video games - which they are - then FMVs are games as well. This review isn’t debating the definition of video game. A video game is some software, built to be fun, that provides an interactive experience. FMVs fit that definition.

Instead, when looking at The Bunker, I’m left with the question of what criteria I judge it on. It is fundamentally an interactive film, so do I judge it as a film, or do I judge it as a game? It’s a bit lacking on both elements, but that’s excusable if you start with the assumption that it should, in fact, be judge as an example of the other. It leaves me in the position of trying to decide what to do, not only with this game, but its entire genre.

It’s the Apocalypse,

and these are the only books you brought. You, my friend, are doomed.

It’s the Apocalypse,

and these are the only books you brought. You, my friend, are doomed.

The Bunker is an interactive film. It follows John, the sole survivor in a fallout shelter somewhere underneath London. He has not always been the sole survivor, and the mystery of what happened in the bunker weaves throughout his story. After an air filter fails, John must find a way to escape the bunker. He explores the different floors of the bunker, and in doing so, relives the experiences and unravels the mystery of why he is the sole survivor.

Gameplay-wise, there is very little gameplay. The purpose of the game is less to play, and more to engage with the story. This is done through point and click mechanics and (failable) quick time events. Pointing and clicking allows John to interact with various elements of his environment, sometimes triggering a cutscene, and sometimes just triggering a bit of information. There are no puzzles, and nothing in particular to solve. The point is John and his journey not only through the bunker, but through his own trauma.

John needs some

serious therapy.

John needs some

serious therapy.

Being an interactive film in theory allows the player to engage with the world at their own pace and in a way that resonates best with them. It’s a method of storytelling that, in theory, grants the player a certain degree of agency in the course of the story, or at least lets them experience it in more depth. Rather than the camera deciding what element of a film the audience is going to be focusing on, FMVs allow the player to linger in whatever moment they choose or engage in them in any order.

This is partly true in The Bunker. That ability to linger in moments is largely present, and the interactive nature did allow me to explore my environment to get a clearer picture of what this world actually was. I enjoyed clicking through computers and notebooks and allowing the story to unfurl in front of me. However, this strategy of film making works when the world is sufficiently immersive to be engaged in. While The Bunker sets up an engaging world and story, the addition of failable quick time events puts that ability to stay immersed at risk.

As an example, near the end of the game, I was midway through a chapter and paused to take a sip of the tea I had been ignoring throughout most of the gameplay. As I picked up the cup, a quicktime event flashed across the screen. I missed it, failed it, and got sent back to the beginning of the chapter. The same footage replayed, and while it wasn’t too terribly long, it was a reminder that this was a pre-recorded world, where the course of events was set, regardless of my input or actions. The immersion was broken, and once it was, the story lost its hold on me, and the game some of its magic.

I’m sure this will

not be relevant at any point.

I’m sure this will

not be relevant at any point.

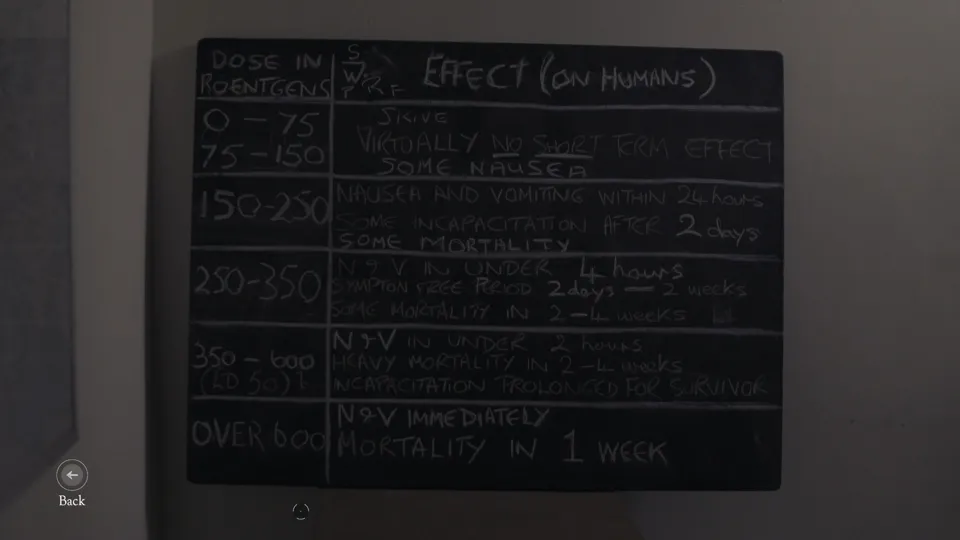

If the game mechanics exist solely as a way to propel the story forward, it’s worth looking at the story. As a concept, it’s excellent. The sole survivor in a fallout shelter is always a fun concept, and I looked forward to how the game explored it. However, as I played, the various plot holes became bigger and bigger, to the point that I started getting distracted by them. If, for example, radiation was leaking into the bunker in sufficient volume to get people sick, how was John still doing okay? How does John still have twenty-six years of food left, assuming a steady diet of 1500 calories per day, since both he and his mother must have been eating before that point? Why is this the least OSHA-safe fallout shelter? In a traditional film, I might forget about these plot holes, but when the plot moves at whatever pace I have when exploring, it lets these small quibbles linger until they become larger distractions.

This is also how the uncanniness of the medium itself comes to the forefront. The Bunker is not my first foray into FMVs. I’ve played through Black Mirror: Bandersnatch several times, and had a grand time with it. It takes a very different approach to the role of player input, and there’s nothing wrong with that. Each game makes of its mechanic what it chooses to tell its story. However, one consequence of that difference is that Bandersnatch succeeds more as a film while also having arguably more player input. While the player doesn’t necessarily control the individual actions of Bandersnatch’s protagonist, they do direct the course of his life, a course which he then follows.

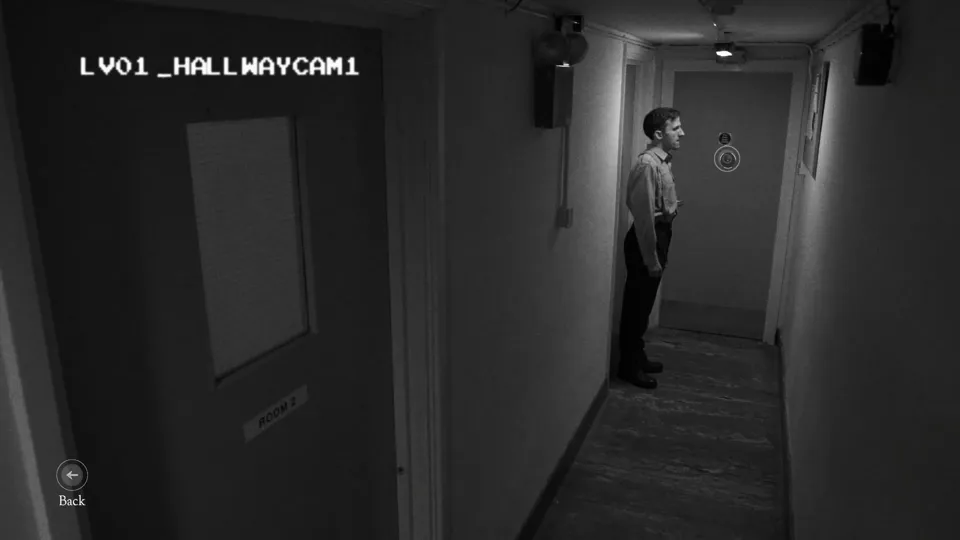

In games where the player directs the character’s actions, there will necessarily be pauses where the character waits for the player’s input, or jumps between whatever their idle animation is and the action animation. In animated games, this is fine. We see an animated character and don’t have the sense that they are a real person - it’s okay for them to stand idle because that’s what animated game characters do. They wait for player input. Watching a live person who is presented less as a game character, and more as a living being - as film does - just standing there, waiting for instruction, is a deeply uncomfortable experience. Indeed, watching an actual human act like a video game character, through over-dramatic behaviours or a complete lack of behaviour, sent me careening through uncanny valley. I imagined this actor being told to stand there and wait for input, and it seemed like something straight out of, well, Black Mirror.

You…you doin’ okay

there, John?

You…you doin’ okay

there, John?

The end result of this choice to make the character’s every action player directed is that John ceases to feel like a neurotypical person. When he waits for command, he is a character, and it breaks immersion. Within his actions, he is so shaped by command that he ceases to feel like he has any agency, which, to be fair, he doesn’t. I could, to a certain extent, justify this within the context of the plot. John has been through significant trauma and now finds himself alone at the heart of that trauma. Of course he won’t be okay. On the other hand, the uncanniness becomes difficult to justify away the more and more John behaves like a character. I wanted The Bunker to be an exploration of trauma and what impact that has on a person. The portrait painted of John with the hues of his trauma ceases to be a recognisable one, and becomes an uncomfortable experience in a way I don’t think the developers intended.

To be clear, this is not a statement meant to imply that neurodivergent people can’t be represented in video games without seeming inhuman. They absolutely can, with Overwatch and To The Moon providing some excellent examples with their autistic characters. I myself am on the autism spectrum, and want to see more kind representations of people like me in the media I enjoy. John, however, is not that representation, and if anything, seems a bit cruel. He does not function without outside guidance, and while the game presents this as a consequence of this being a game, because this is also a film, the argument could just as easily be made that he is this way because of PTSD and the trauma of his past. The choices the story makes on the player’s behalf are ones that highlight John’s inhumanity, and thus divorce the player from being able to empathise with him. If he is indeed neurodiverse, this makes a statement about the ability of people more generally to empathise with the neurodiverse community, and reaffirms rather than rejects the stigmas that have been placed upon us.

I find it difficult to decide how I feel about The Bunker. I wanted to like it, and in some ways, I do. It tells a compelling story, and I mostly enjoyed my time with it. However, its choice of gameplay elements detract rather than add to the story, and the decision to direct individual actions rather than plot turns makes John much less believable as a human being. It’s because it succeeds as neither a film nor a game nor the intermingling of the two that I’m left disappointed by The Bunker. I wanted to enjoy it, but in the end, it feels hollow.

Developer: Wales Interactive

Genre: Fmv

Year: 2016

Country: United Kingdom

Language: English

Play Time: 1.5 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/pKWl9-jqOr8