Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood

There is a trend I’ve noticed lately in several women-centered stories, most notably in Black Book , but in several other games as well. As queer and female narratives become more and more prevalent in games, they are accompanied by the redemption and resurgence of witches and witchcraft. These stories of powerful women who reject societal norms, or who exist within their own spaces are being retold and reframed as tales of positivity and companionship.

I love it.

That reframing alone was already going to endear me towards the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood, but happily, there is so much more to this game than its concept alone.

<.<>.><.<

<.<>.><.<

The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood is a visual novel game telling the story of Fortuna, a witch sentenced to a thousand year exile after predicting the demise of her coven. After two centuries of isolation, Fortuna attempts to break out of her imprisonment, summoning a forbidden behemoth to provide her the power to do so. Fortuna finds that, upon partnering with the behemoth, her fortunes shift. She is left to grapple with the consequences of her decision, and the new power she has been given.

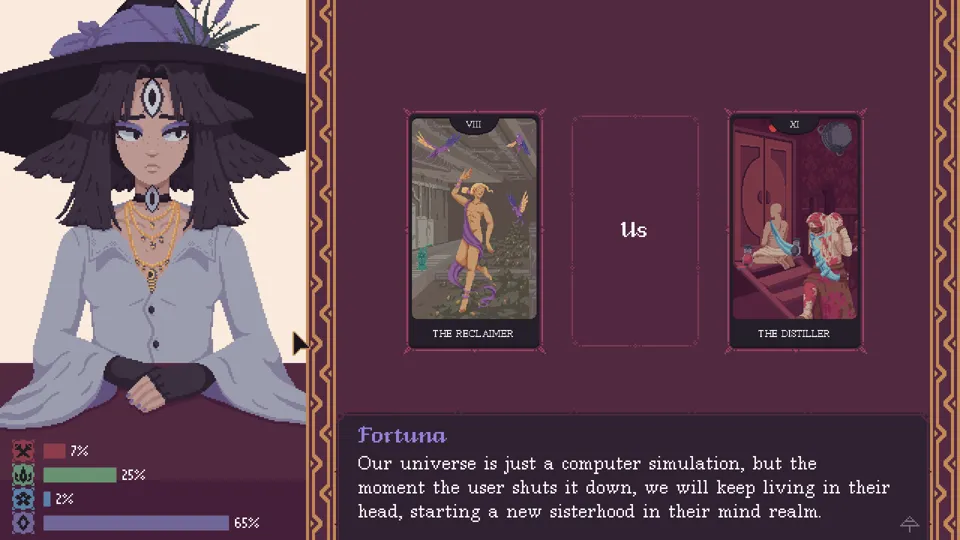

Like many visual novels, The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood has limited gameplay mechanics, with much of the focus being on the creation of custom tarot cards and using them to read characters’ fates. Rather than using a standard tarot deck, however, The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood allows players to design their own tarot cards, adding a fantastically fun and creative mechanic. These cards are then used to tell the futures of Fortuna’s various visitors, and shape the course of the story.

Interestingly, the game takes a hard mechanical shift in its third act, more or less setting its previous gameplay loop aside and replacing it with a political campaign mechanic. Instead of relying on a deck, this phase of the game requires the player to manage a political campaign, balancing appeals to various demographics and courting allies. It is a bizarre shift that, while still fun, reflects an odd understanding of player agency and the impact of a player’s choices.

I wouldn’t know anything about that.

I wouldn’t know anything about that.

At the core of most visual novels is the idea that the story being told is an interactive one. This means the story engages the player in some way, but equally, the player has the ability to influence the story, even if that influence is solely limited to the influence they have as a result of observation. For most stories, this means the player has the ability to influence the course and outcome of the story, with their choices making a meaningful difference in how the story plays out. Indeed, the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood emphasises that it is a story within this mould, reminding the player from the outset that their choices have consequences, and to take care with the decisions they make.

For much of the game, the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood stays true to this promise it made at the start. Even if they player’s choices don’t immediately impact the overall course of the story, they impact the details enough for the choices to still feel meaningful. For example, in one tarot reading, I told a witch she should be honest with her partner that she was a witch, and that he would still love her. A little while later, she returned, saying I’d been correct, and they were very happy together. The same character then returned at the end of the game, emphasising that I had been helpful in the game’s climax. This is a perfect illustration of how player choice can feel both meaningful and still be manageable within a contained game. Seeing the consequences of my actions reiterate over and over made them feel more real, and like I had played a role in the outcome. Making those consequences essentially extra spice in the recipe the game had already concocted also made any variation of the choice I made fit within the story’s scope. Whether I helped this witch or not ultimately only impacted me and how involved I felt with the story.

The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood understands fundamentally how to incorporate player choice within a fixed narrative. This makes the shift in mechanics and the dilution of player agency in the third act even more baffling.

Fun fact! My campaign manager and I had this exact fight when I ran for city council.

Fun fact! My campaign manager and I had this exact fight when I ran for city council.

In the game’s third act, the mechanics shift from reading the fortunes of Fortuna’s visitors to managing a political campaign as Fortuna seeks to become the new leader of her coven. This is a shift that the player is forced to engage in, regardless of the Fortuna they’ve built for themselves and the person whose story they’re telling. Rather than allowing the diversity of player choice within a fixed story, the player gets railroaded into a path the game chooses for them. While this is partly justifiable as the various NPCs exerting their influence over Fortuna, Fortuna’s commentary and dialogue choices make this feel significantly more like a choice she is meant to make at this point rather than one that has been foisted upon her.

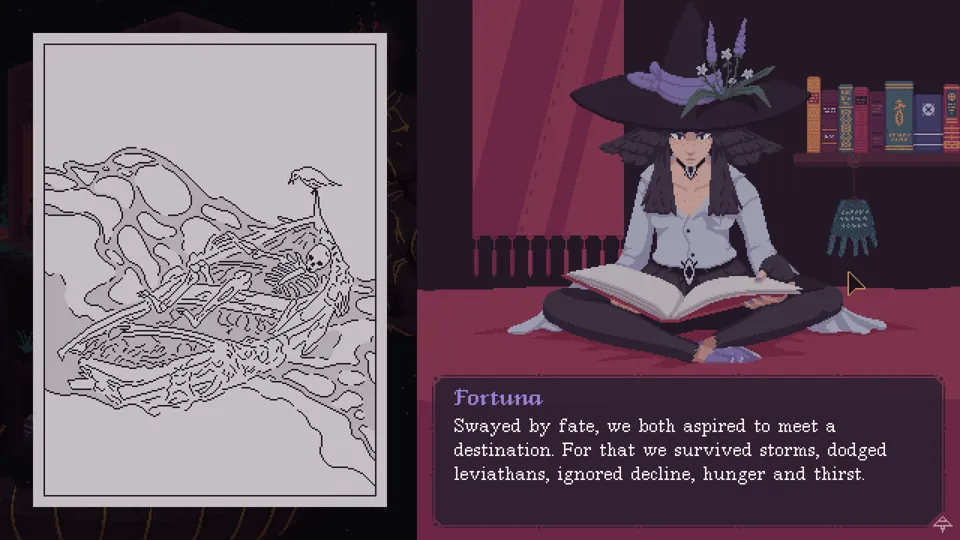

This sense of being railroaded continues throughout the game’s final act, including into the ending itself. The character I’d cultivated over the past few hours didn’t seem to be possible within the scope of the story the game was telling. The fortunes my Fortuna told became disjointed and nonsensical as I tried to reconcile the game’s expectations with my own. What was likely meant to be a heartfelt and emotional ending instead became a confusing mess as I watched my player agency be replaced with the game’s preset narrative.

And oh, the witches do desire Abramar.

And oh, the witches do desire Abramar.

This is not the first time I’ve run into a loss of agency in a story game, nor the first time that it’s felt like a betrayal by the game. In my review of the Batman Telltale series, I explored the limits of player choice, and how the game’s idea of the consequences of a player’s decision and the player’s ideas can sometimes clash horrifically and create a sense of betrayal by the game. The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood in some ways echoes this with how it chooses to construct its ending, and what elements of player agency it overrules. However, it also differs in that it creates an entirely new gameloop and mechanic to overrule that player agency, demanding that the player now abandon everything that brought them to this point and replace it with something new.

To be clear, the political campaign mechanic is still fun, albeit less so. There is still a story being told, but it is one that doesn’t take into account who Fortuna is and the choices she made from the outset. All the fun mechanics in the world can’t overrule that sense of betrayal of player agency.

What I find most entertaining, though, is that my sense of betrayal pales in comparison to some of the rest of the fanbase, and it’s this discussion that I find the most interesting.

No matter what I play, I will always just be thinking about food.

No matter what I play, I will always just be thinking about food.

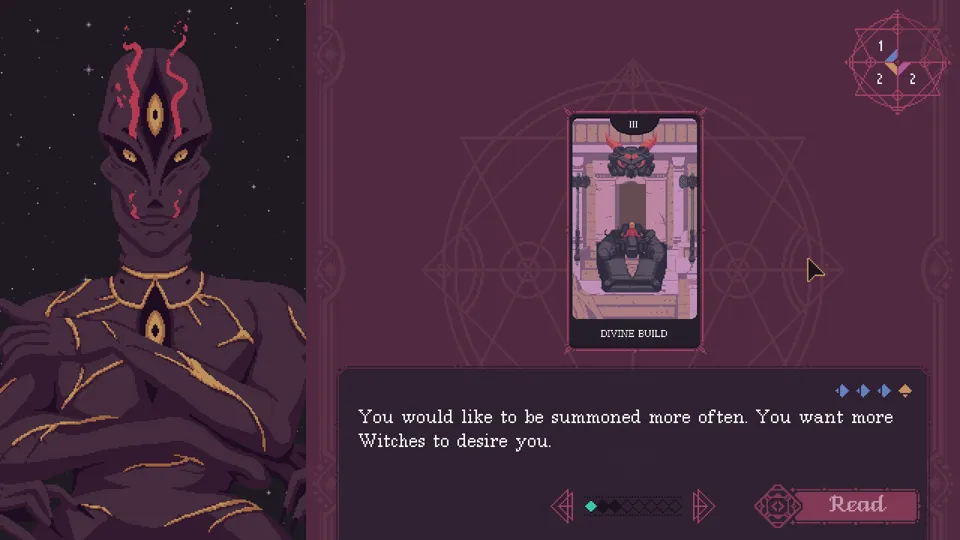

The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood is not a game that shies away from sex. On the contrary, it loves sex and relationships, exploring them in wholesome and sex-positive ways. Characters are in a wide array of relationships, and express a range of sexual orientations and identities. Within this context, it’s not unreasonable for the player base to view Fortuna’s relationship with her behemoth-buddy Abramar as a potentially sexual one. When they tell each other that they love each other, and when Abramar discusses his previous sexual relationships with witches, the game feels like it’s building up to a decision for Fortuna to elope with her behemoth. And yet, she never does. The option never presents itself.

One of the most frequent comments I’ve found in forums discussing the game is the almost meme-ification of Fortuna’s lack of sexual relationship with Abramar. The devs themselves have made a joke out of it, even offering an Abramar-themed dildo as a prize for a contest related to the game. In many ways, the most important choice the game could present - Fortuna’s ultimate relationship with this demon who has come to define her life - is never even presented to the player. The ultimate expression of player agency and player determinism of the story is not only stripped away, but never permitted in the first place. Fortuna is never allowed to be who the player envisions her to be. Fortuna is and always will remain an expression of the devs’ version of the story, not the players’.

To me, though, Fortuna being unable to sleep with Abramar is not a betrayal of my player agency, at least not in the same way that Fortuna being unable to be a complete sociopath is, and it’s here that I look at my expectations for player agency and wonder if I’ve applied the wrong model. I played through the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood expecting Fortuna to be a blank slate, ready to be painted with whatever fate I could concoct. The reality, though, is that Fortuna is not and was never going to be a blank slate. I went into this game with the idea that I was playing a Mass Effect-style character game, when what I actually had was more akin to the Witcher.

You can’t read that, but it says “oh my god, this review is still going, and now it’s talking about the Witcher for some reason.”

You can’t read that, but it says “oh my god, this review is still going, and now it’s talking about the Witcher for some reason.”

Within RPGs, there are two schools of roleplay. There are games (like Mass Effect and Skyrim) that present the player with more or less a blank slate of a character. Sure, there might be some slight constraints - Shepard needs to be a Spectre, for example - but within those soft constraints, the player is free to build whatever person they see fit. My Shepard can be an absolute ass or a perfect paragon. Both are valid builds, as is everything in between. The only limiting factor for what my Shepard does is me.

However, there are also games where the player isn’t creating a character, per se, but is slotting themselves into the story of a pre-existing character. These games (like the Witcher) place hard constraints on the player, limiting them to the range of actions that that character would feasibly take. I can have my Geralt be an ass, for example, but that ass-ness will never extend to an action like selling Ciri to Nilfgard. That exists outside what the character would do, and so it becomes impossible. Critically, these games not only don’t allow the player to take these actions, but don’t present a way that a choice like this could be made. It doesn’t occur to Geralt that this is an option, so the player never has the opportunity to consider this. Player agency is still respected, but that respect is shunted down the paths that are plausible within the world the game has built. This shunting and filtering of options is vital. If every potential option is presented, and then some denied, the player feels like their agency isn’t respected, and the choice was never theirs to begin with. A game that is limiting options needs to filter its options if the player is to feel that they do have agency within the game.

The Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood doesn’t filter. While some choices are obviously not available within the game, others are, but not in a way that feels satisfying to the player. Fortuna, despite what is presented, is not a blank slate. She has a life and a character from before the player came into the picture, and her actions within the game need to fit within that narrative. I cannot, for example, play Fortuna as an absolute sociopath because she isn’t one. My sense of betrayal stems from the game letting me believe for most of its playtime that that course was possible, and not telling me until the last moment that it wasn’t. It’s fine if Fortuna isn’t a sociopath - the betrayal stems from the game never letting me know that wasn’t an option.

The same is true for the players thirsty for Abramar. While not explicitly stated, the game hints in several points that Fortuna is asexual and aromantic. Within this context, there was never a possibility of the player romancing Abramar, but the game doesn’t filter out the options that lead the player to believe in that possibility. The betrayal of agency here isn’t in the player not being able to sleep with an otherworldly demon, but in never being told it was impossible.

It’s this blending of the idea of character and RPG that is the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood’s biggest failing and biggest source of frustration. Players come into the game expecting to be able to tell themselves a story, when in actuality, the limitations of the character have already shaped numerous elements of the story without ever informing the player. There is agency, but only within certain channels, and those channels are never revealed.

My destination at this point is the end of this review.

My destination at this point is the end of this review.

With all of that, you might think I disliked the Cosmic Wheel Sisterhood, or that this is in some meandering, wordy way a negative review. It isn’t. I loved the game. I devoured it, and then, as Fortuna predicted, let it just simmer in my mind for quite some time afterwards. It does a stellar job telling its story and giving the player unique ways to interact with that story and consider their own role as storytellers within a predetermined narrative. Its art and sound design are fantastic, and I thoroughly enjoyed my time with it.

What I’m left with, though, is the question of whether there is a way to tell a fixed story while still making me feel like I have agency. Likely there is, and it’s probably buried somewhere much deeper in my library. However, for now, I will be content with three good hours of immersive storytelling, and one hour of questioning the role of agency in games.

Developer: Deconstructeam

Genre: Visual Novel, Indie

Year: 2023

Country: Spain

Language: English

Play Time: 3-5 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/z47WlJXgGTQ