Darkest Dungeon

I admire the sheer range of roguelikes out there. Whether they’re card games, action games, or something in between, the number and range of them makes for a satisfyingly broad array of ways to play with the mechanic. Indeed, it’s so broad at this point, that I almost hesitate to call it a genre anymore. At some point, it became a mechanic, a way to make a game fit within some other genre and make a unique iteration of that genre.

One consequence of this, though, is that some games feel as though they felt obligated to add roguelike mechanics, or add them in a way that doesn’t play to the genre’s strengths.

Camping! Everyone loves spooky camping!

Camping! Everyone loves spooky camping!

Darkest Dungeon is a roguelike dungeon crawler. It’s labelled as an RPG, but I don’t entirely agree with that label for reasons I’ll get into. You play as an adventurer, sending expeditions of adventurers into the ruins of your family’s manor, trying to break whatever curse lies at its heart. The player can then use the loot gathered in these dungeon crawls to upgrade the various buildings in the town to better train and equip their adventurers in a perpetual cycle of improvement, looting, and improvement.

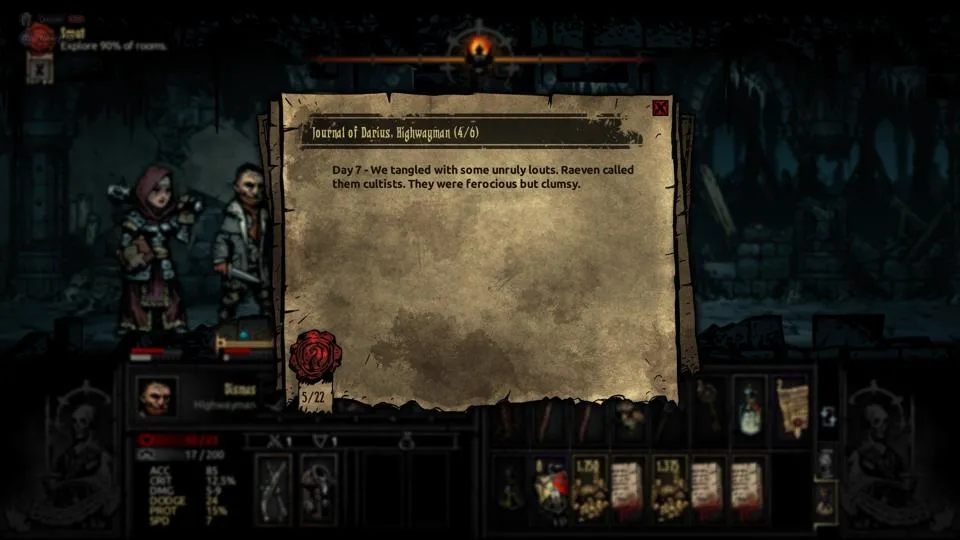

The actual dungeon crawls represent the bulk of gameplay. Players traverse procedurally generated dungeons, fighting monsters, disarming traps, and collecting loot. They have limited inventory space, and so must make choices between things like having light and food, or scampering out of the dungeon, laden with fun treasures. In many ways, Darkest Dungeon is also an inventory management game, with players needing to make decisions about how much they’re willing to sacrifice, and what risks they’re willing to take with the limited space available to them.

It’s me, hi. I’m the unruly lout, it’s me.

It’s me, hi. I’m the unruly lout, it’s me.

One consequence of this slow build approach and procedurally generated dungeons is that the game very much becomes a grind of leveling up lower level adventures, equipping them, and constantly needing to grow to support this levelling. With the price of each upgrade rising, and an increasingly large paddock of adventurers, the player becomes stuck in either focusing all their efforts into their best combination of adventurers, or distributing their resources and having a weaker but more resilient party overall. This dilemma becomes especially acute when coupled with the death mechanic in the game. Once an adventurer dies, they are dead, with all the resources and items invested in them disappearing with them. Players need to be aggressive to make progress in the game, but that aggression is also discouraged through the knowledge that, should an aggressive move not pay off and an adventurer die, a not insignificant investment is lost with them. There is a dichotomy between what the game wants the player to do to succeed and the risk the player knows they’re running if they do what the game wants them to do.

I feel like this estate really needs a TLC, personally.

I feel like this estate really needs a TLC, personally.

In practice, then, I found myself often playing conservatively, distributing my resources equally across all my adventurers, and creating a paddock of high level, but mediocre adventurers, rather than investing wholly in a consistent party of four. This meant that each of my dungeon runs generally used a different party, with a different focus or different strengths between them. One might specialise in bleed, for example, while another liked playing in darkness. The game provides a fair amount of variation in party composition and focus, and encourages the player to explore these different combinations through its rest and recuperation mechanics, and its need for adventurers to take breaks and be cured of various maladies. While, on the surface, this availability of a range of styles would suggest runs would vary substantially, in practice, they don’t, and the game becomes a grind.

For every different party I could build, the actual gameplay stayed more or less the same between them. I stock up on supplies, with the quantity varying on the party’s skills and destination, but the supplies themselves remaining the same. I traipse through 90% of the dungeon’s rooms, or win all of the battles, or collect artefacts, while an narrator narrates my journey. The party’s experience in each combat is more or less the same, and the same enemies appear in each combat in a given region. Though the map of the dungeon and the specific distribution of the treasure within may be random, the experience itself is not. It all eventually gets to a point where dungeons are being run just to be able to do something more interesting, except with the knowledge there isn’t really anything more interesting to be found.

I have surprised some maggots. Truly, I am fearsome.

I have surprised some maggots. Truly, I am fearsome.

This is not to say Darkest Dungeon is a bad game. As much of a slog as the game as a whole can become, the time until that point sinks in is fun. The combats are well-designed, and provide a challenge and the need to think tactically about any given situation. The stress and light mechanics are a great addition that add more long-term planning and strategy to the traditional dungeon crawl experience. There is a lot of fun to be had with Darkest Dungeon, at least until the point when you realise that it’s the same thing, over and over, or until your lead hero dies, and you’re faced with the dismal prospect of levelling up someone new from scratch. It’s at that point that the veneer rubs off, and you’re left with the realisation that this is a mire, and you are stuck trying to plow through it for reasons you can’t begin to recall.

Developer: Red Hook Studios

Genre: Dungeon Crawler, Roguelike

Year: 2016

Country: Canada

Language: English

Play Time: 50-60 Hours

Youtube: