Dave The Diver

CW: This review contains descriptions of animal abuse.

I’m going to preface this review by saying something that I think has more weight on this review than I intended it to, but which is probably important to call out for reasons that will become immediately obvious as soon as I say it.

I’m vegan. I have been vegan my entire adult life. A game predicated on harpooning fish and serving them as sushi reflects precisely zero primal desire, nor do I align myself with the values of this game.

I call this out, though, not because I think less of Dave the Diver because it’s a game about a man and his unabashed love for sushi - I don’t - but because the ethical lens through which I’m viewing Dave the Diver informs how I ultimately feel about it. My lens is coloured by the knowledge of the impact of fishing, and it’s a hard lens to remove. I don’t believe this makes me unqualified to review Dave the Diver, but let this be a different kind of content warning. This review says as much about me and how I view the world as it says about Dave the Diver.

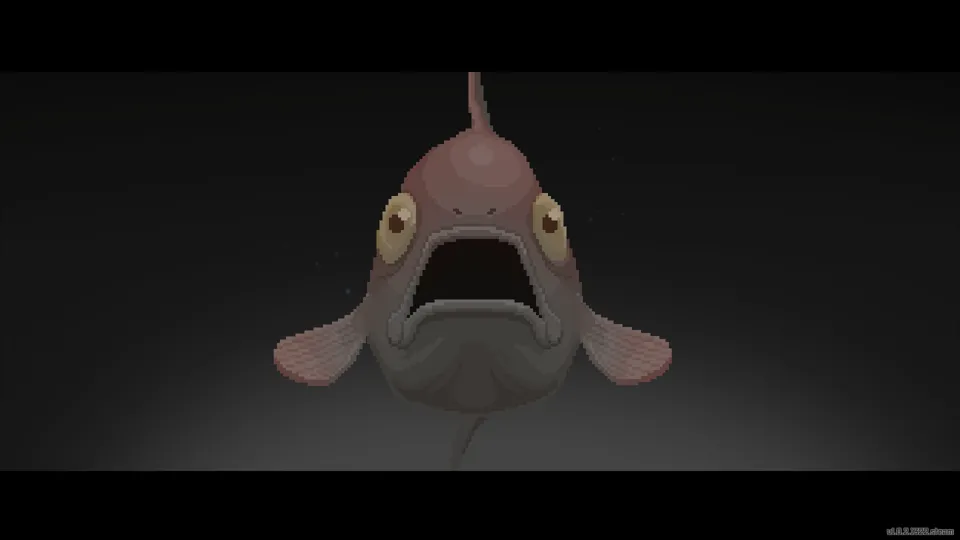

Be not afraid, fish, for tonight, we are all doomed together.

Be not afraid, fish, for tonight, we are all doomed together.

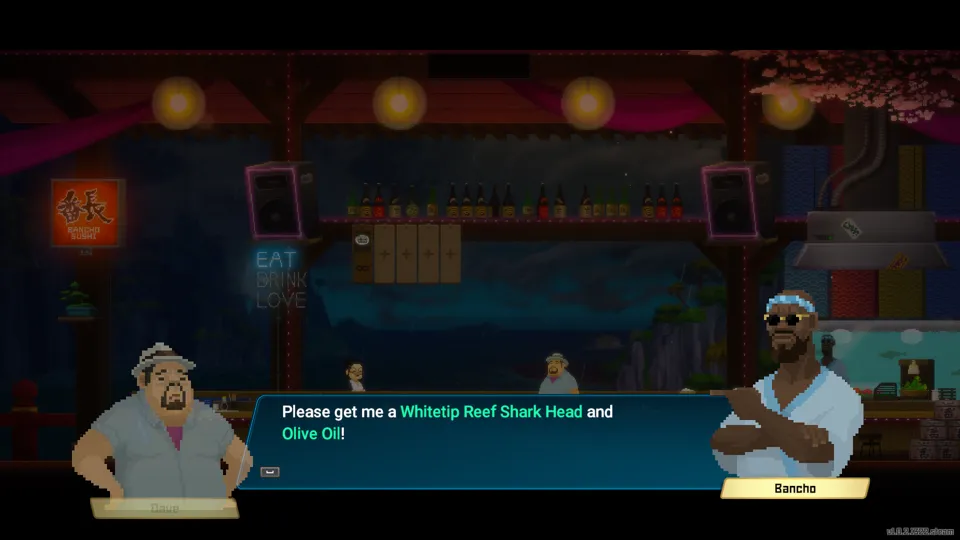

It’s difficult to pin Dave the Diver into a particular genre. The bulk of its gameplay is adventure gameplay, with the titular diver, Dave, diving into a blue hole filled with fish, dolphins, and other sea creatures to find tasty fish to turn into sushi. However, that adventure gameplay exists in service to a restaurant management game, with Dave then later designing menus, hiring staff, and serving customers. These two genres are then punctuated by a variety of minigames, ranging from racing games to Hololive DDR sims. Dave the Diver is all over the place on the genre map. This isn’t a bad thing, but it is an interesting thing, and one that potentially speaks to a greater trend in games, namely the nullification of genre.

In my Cult of the Lamb review , I talked about that game’s blending of genres, and how the shallowness of each did a disservice to the game as a whole. The two genres didn’t feed nicely into each other, with each detracting from the other’s time. With Dave the Diver, the narrative necessity for Dave to be diving plays nicely into the restaurant management element of the game. Dave must dive to catch what is going to be on the menu that evening, and the menu is a direct reflection of the player’s efforts. Rather than falling into prescribed paths, Dave’s adventuring leaves ample space for players to be creative about the risks they’re willing to take, and what they’d like their menus to focus on. The lack of time constraint on the dives, too, allows the player to take their time with the dive and enjoy the process of exploring the depths. It is, on the whole, a much better blending of genres, and a good representation of what genre blending can be.

huehuehue

huehuehue

One consequence of each phase of Dave the Diver dovetailing nicely into the next is that it is incredibly addictive. The system of quests and constantly changing dive environments provide incentives for the player to keep diving again and again, with the restaurant management providing just enough of a change of pace to mask how much time is being spent on the game. I often found myself saying I’d just play a single day, only to look up two hours later to realise the day still hadn’t ended. The game does an excellent job of making the player feel like Dave and stay engrossed, even when the player has, in actuality, been doing the same dive for hours.

This is further compounded by how the game chooses to reveal its content. Throughout the first few hours of the game, there are obvious hints that there are elements the player is going to unlock later in their playthrough. The player upgrades and manages their equipment and quests through an in-game phone, for example, and many of the apps start greyed out, becoming selectable as the game progresses. Similarly, there are items and recipes Dave encounters throughout his adventures that suggest there is always more to discover. I didn’t fully unlock the farm until the 20th hour of play, for example, and I have no doubt there is even more content I haven’t begun to touch.

This slow reveal of content contributes to Dave the Diver’s sheer addictiveness. In addition to the game mechanics lending themselves well to repetitive play, this slow reveal of content means that there are constant dopamine hits from unlocking something new, and a constant sense that there’s an entirely new area or mechanic to explore. The game continuously remakes itself, and in so doing, keeps the player hooked. What starts as an adventure game with a restaurant manager tacked on becomes Stardew Valley, Farmville, DDR, a stealth game, everything imaginable, all rolled into one. It is a game that adds in new genres so frequently, that the question of genre itself ceases to have any meaning. It is simply telling the story of this sushi restaurant, with that story becoming more and more holistic as the game progresses.

I’m pretty sure this is what my Instagram Cooksta posts look like as well.

I’m pretty sure this is what my Instagram Cooksta posts look like as well.

In some ways, this constant addition of new content feels predatory. Every time I felt like I’d reached a point in the game where I could feel comfortable putting it down, it would throw something new at me that I felt I had to explore. Each of the new additions was a shallow facsimile of the genre it was adding in, but a sufficiently good facsimile that I was willing to let it slide. It didn’t have to be an exemplar of the genre to still add something to this game, and to break up what would otherwise become a repetitive game loop. The addition of farming and feeding a cat and checking on fish added daily chores that became part of the loop.

At about the fifteenth hour, as I dove into the water and heard the happy swimming music once again, I reflected on what I was doing. I already knew what I wanted to catch, and had optimised my loadout as best I could to do so. I already knew where I wanted to go, what I’d probably find, and the menu I was hoping to make. Why was I still doing this? Why was I still playing this game if I had, in my view, beaten it? I still had fun, but why?

I describe this slow unravelling of content as bordering on predatory because it is designed to captivate players like me, players who are looking at this game, but also the next. Players who need a shifting environment to stay motivated and interested. Players who lose interest if they don’t see the point in what they’re doing in the here and now.

The central control element of Dave the Diver is a phone filled with apps. I find that telling, because Dave the Diver feels like a game designed for eternally connected people like me. I may not be on my phone constantly, but I am terminally online, bathed in the glow of constant noise, information, and change. Dave the Diver reflects this, bombarding me with more tasks and activities than I could ever hope to engage with in the hope that something will stick, and I will stay. It works, of course. The constant change keeps my distractable brain hooked and excited for whatever gets waved in front of me next, and it’s not until something else throws me out of the game that I actually recognise what’s happening. I am addicted, because the game is designed to be addictive. It’s clever and understands how to do it, and it does it extremely well.

But something else did come along, and now I’m here, finally reflecting as I should have done a week ago.

I don’t know how or when Momo became a good name for cats, but I’m here for it.

I don’t know how or when Momo became a good name for cats, but I’m here for it.

I have a friend - we’ll call him Abadon - who does not view the world in the same way I do. While I was playing this game, Abadon talked about trying shark fin dumplings at a restaurant he went to, and his thoughts on shark fin as a food.

I was not thrilled that he’d done this.

I’m going to go off on a tangent here, because it’s important to understand. Shark finning is the practice of catching sharks, hacking off their fins while they’re still alive, then dumping the - still alive - shark back into the water. There, it dies a painful death of blood loss, suffocation, or being eaten by some other animal. This practice is done because shark fins are seen as a luxury item in Chinese culture. Chinese weddings often feature shark fin soup, and fine dining restaurants - like the one my friend went to - have it on the menu as a symbol of their fanciness. The shark fins aren’t added in for nutritional value or for flavour (if anything, they’re a bit a flavourless). They are instead textural additions, added for status and as a symbol of humanity’s victory over the shark.

Over a hundred million sharks are killed each year because of this desire for a status symbol. 60-70% of the world’s sharks have been killed in the past few decades as a result of the desire for shark fins. This has, in turn, had a disastrous effect on the health of marine ecosystems, especially in coral reefs. As apex predators, sharks keep the populations of other fish in check. Without sharks, fish like parrotfish can feed on coral unchecked, destroying the reef, and the habitats of dozens, if not hundreds of other species. The practice of shark finning, beyond the sheer cruelty of it to individual sharks, is monstrously destructive to life on Earth.

I am, as I said earlier, vegan. I have been for many years. I know that, in the time I’ve been vegan, global meat consumption has increased , especially in countries with rapidly growing middle classes, like India and China. I know that I, as a solitary vegan, have very little impact on the meat industry. Boycotts as a trend don’t work to change industries unless truly done en masse, which, even with the growing awareness of the many , many harms of the meat industry, is not happening. I know that Abadon’s one serving of soup doesn’t prevent shark fishing, nor would his refusal to order it change any one shark’s fate.

Markets are, however, the product of norms and demands. Markets exist, and the conditions within those markets exist because of what the consumer base accepts. What the consumer base accepts is, in turn, shaped by the norms our society, and what we’ve decided is and is not acceptable. When we express revulsion at child labour in meat packing plants, for example, we do so, not because of the horror of the meat packing industry, but because of the societal norm of not exposing children to that horror. We as a society have decided that children are fairly innocent, and should be treated as such.

Meat consumption as an industry exists because there is no societal norm that extends empathy to non-human animals in a tangible way. We have animal welfare laws, but these do a poor job protecting animals in industrialised farms from being tortured, maimed, and abused as a matter of best practice . We believe our pets are members of our families, but routinely euthanise nearly a million housepets each year because there is no place for them. Norms exist in a self-reinforcing bubble, but a bubble nonetheless. They can be changed or broken entirely, as illustrated by the fact that there are no longer Jim Crow laws, and I have the ability to vote independent of my partner’s preferences.

This is what I see as the actual impact of being a vegan. I can’t change the meat industry on my own. I can’t stop the slaughter of billions. What I can do is refuse to take part in it and make sure those around me understand why I do what I do, and why it matters to me. I can’t change an industry, but I can do my best to reshape the norms around me, and influence those I care about to reconsider what norms they accept, and what price they’ll pay for them.

This brings me back - finally - to Dave the Diver.

please don’t do this, game

please don’t do this, game

As Dave dives through the blue hole, he encounters dangerous fish. Some are tiny and mostly harmless, and Dave can dispatch them with ease. Others are sharks.

The sharks in Dave the Diver are universally depicted as hostile. While Dave can avoid them, they are fast, do a lot of damage, and - at least in the early to mid game - require a fair amount of planning to take down. As enemies, they are well-designed, and provide a good gameplay challenge to the player. As a game element, they’re a welcome addition to the blue hole, requiring careful route planning, or good combat skills.

Shark meat is also the most consistently valuable menu item in the sushi restaurant. There is a strong incentive for players to hunt the sharks of the blue hole. Upgrading the shark menu options to their fullest potential requires killing shark after shark. Near the end of the first month, there is a special shark event that further incentivises the player to hunt down every shark they see to maximise the profits they make in their sushi restaurant. This is a game with a very clear view of what sharks are - they are dangerous, they are delicious, and they are valuable.

Dave the Diver sets a very clear norm. In a world where global ecosystems are at risk because of the commodification of a critical species, Dave the Diver furthers the norm that this is all okay. It furthers that norm of exploitation, and makes it difficult for the player to refuse to engage with it.

…neither do I. :(

…neither do I. :(

As I played through Dave the Diver, I thought more and more about two other games I’d played that felt similar - Abzu and Alba . Both are radically different games, both from each other and from Dave the Diver, but the comparison still feels valid to make. For both Abzu and Alba, there’s an admiration of the world the player has been invited into. The player is a welcome guest into a non-human world, be that an underwater one, or one viewed through the lens of a camera. The player is asked to participate in the world, not as a hostile or destructive entity, but as one that recognises where they are and the role they can play, and chooses to engage with the world on its terms. It sets aside the human, and asks that we instead consider the beauty and inherent value of the non-human elements around us.

Dave the Diver doesn’t do this, nor do I think it ever set out to. Dave the Diver has a fundamentally different view of what the natural world is. While its loading screen populates with fish facts, these aren’t meant to make us better appreciate the world we’re seeing in the blue hole. The value of the life of the blue hole is not in its species name or its biodiversity, but in how we kill it. The value gained from it is monetary, and we are judged based on how much of that monetary worth we can dredge up from its depths.

The main questline of Dave the Diver follows Dave as he tries to save the Seapeople, a race of merfolk whose world is crumbling due to - never explicitly stated - climate change. The only time Dave the Diver engages with the natural world is in terms of its impact on humans. The main story is not one that ever recognises what Dave is doing - indeed, the Greenpeace characters are comic relief villains. Instead, it takes an extreme anthropocentric view, asking its players to view the sea as a body to be exploited, while dressing up that horror in music evocative of beauty and exploration. Its adventure elements are massacre, and once I saw it, I couldn’t unsee it.

The norms that Dave the Diver sets of how oceans should be viewed and sharks in particular are not norms that fundamentally reshape industries. One game espousing a morally trouble position doesn’t change the world. What it does do, however, is shape the minds of those who engage with it, helping them to view the world through the eyes of its morality system, and to engage with a fundamentally destructive anthropocentric position. The constant unveiling of content and constant triggering of dopamine receptors helps make it even more difficult for a player to think critically about what they’re doing and what the game is actually saying to them. Instead of thinking and engaging, we’re acting, going through the motions, and looking ahead to whatever quest gets fulfilled or whatever content gets shown next. The addictive design is likely intentional to keep players engaged, but it has the unintentional side effect of masking the message and morals of Dave the Diver, and the horror of what it’s actually saying.

Dave the Diver did indeed receive many awards.

Dave the Diver did indeed receive many awards.

Sometimes, when I write these reviews, I feel a bit insane. I recognise that, on a gameplay level, Dave the Diver is perhaps a bit problematic, but not in any immediately identifiable way. The addictive design that I see as potentially predatory clearly isn’t viewed as such by the rest of the industry, and so I’m left with the question of whether I’m just grasping at straws. Each individual element of the game is fun and delightful, but when put together, it creates a picture I can’t endorse. I can’t decide if my reasons are valid for anyone but me, or if I spent so long thinking about this game and about Abadon’s soup, that I just can’t let it go anymore.

There is a lot of fun to be had with Dave the Diver. The sheer number of hours I spent playing it speaks to that. What that fun masks, though, is a fundamentally destructive ethos, and a game design that preys on minds like mine. It’s fun, but in the same way crushing a penny on a train track is fun. There’s an inherent destructiveness and disregard for the participant’s welfare, and sometimes, there’s blood.

Developer: Mintrocket

Genre: Adventure, Management

Year: 2023

Country: South Korea

Language: English

Play Time: 30-40 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/4yiRnncGkrU