Dear Esther

CW: This review contains discussion of self-harm, suicide, intimate partner violence, and violence against women.

I’m going into this review knowing that Dear Esther is an indie darling, one of those games that led to a small revolution in the industry. It’s the game that more or less founded walking simulators as a genre, and it’s one of those games that, when people ask whether video games can be art, is pointed to as an indicator that they can and ought to be. I know the minefield I’m walking to, and I embrace it anyway.

Because the thing about these reviews is that I’m not generally setting out to review a game in the traditional sense. I’m not here to tell you whether to buy a game or not, or what the mechanics are, or any of those things. These reviews are more musings on the game I’ve played, and what impact it left, and whether it succeeded in what it set out to do. They’re deeply subjective bits of writing, and I don’t begin to pretend otherwise.

When I say, then, that I despised Dear Esther, know that that’s not because it’s a walking simulator, or as an indictment of any of those who have hailed it as a work of art. It can be both a thing of beauty, and a piece of media that I hated engaging with and think tells an entirely incorrect truth.

It is pretty, though. Let’s get that out of the way.

It is pretty, though. Let’s get that out of the way.

Dear Esther is a walking simulator, meaning there’s no puzzles or gameplay or anything that is usually thought of as traditional game elements. Instead, the player is asked to move through the space, exploring their surroundings, and listening to the snippets of narrative.

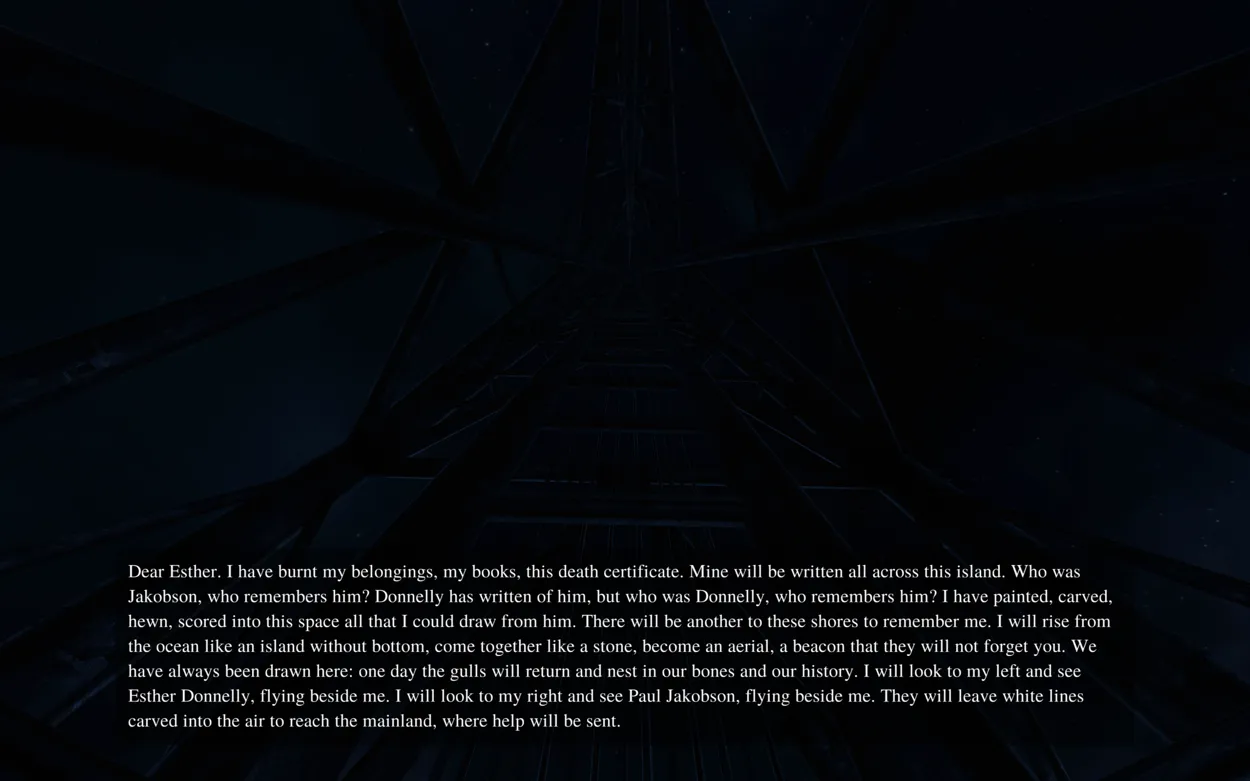

In Dear Esther, that narrative is told in the form of unsent letters written by the male protagonist to his dead wife, Esther. They tell the story of the island, why he’s here, his intention, and the stories of others who have been here before him. Through these snippets of narrative, we learn a jumbled, fever-haze version of the story of this man and Esther, how he killed his wife in a drunk driving accident, is wracked with remorse, and is now determined to throw himself off the radio tower so he can be with her again. The game ends with the player doing exactly that, leaping from the island’s radio tower, past the island’s cliffs, and soaring past the unsent letters, folded into boats and left to drift out to sea. The music is poignant, the visuals sweeping, and the overall air of the ending one of freedom and tranquility.

This game is an hour long, and at about the point that I figured out what the protagonist had done, I counted every single minute. I yearned for a dash button so I could get out of this game as quickly as possible. I did not want to be here with this man, and I did not want this game to try and fail to elicit my sympathy for him.

Great island, though. 10/10 on the Hebrides experience.

Great island, though. 10/10 on the Hebrides experience.

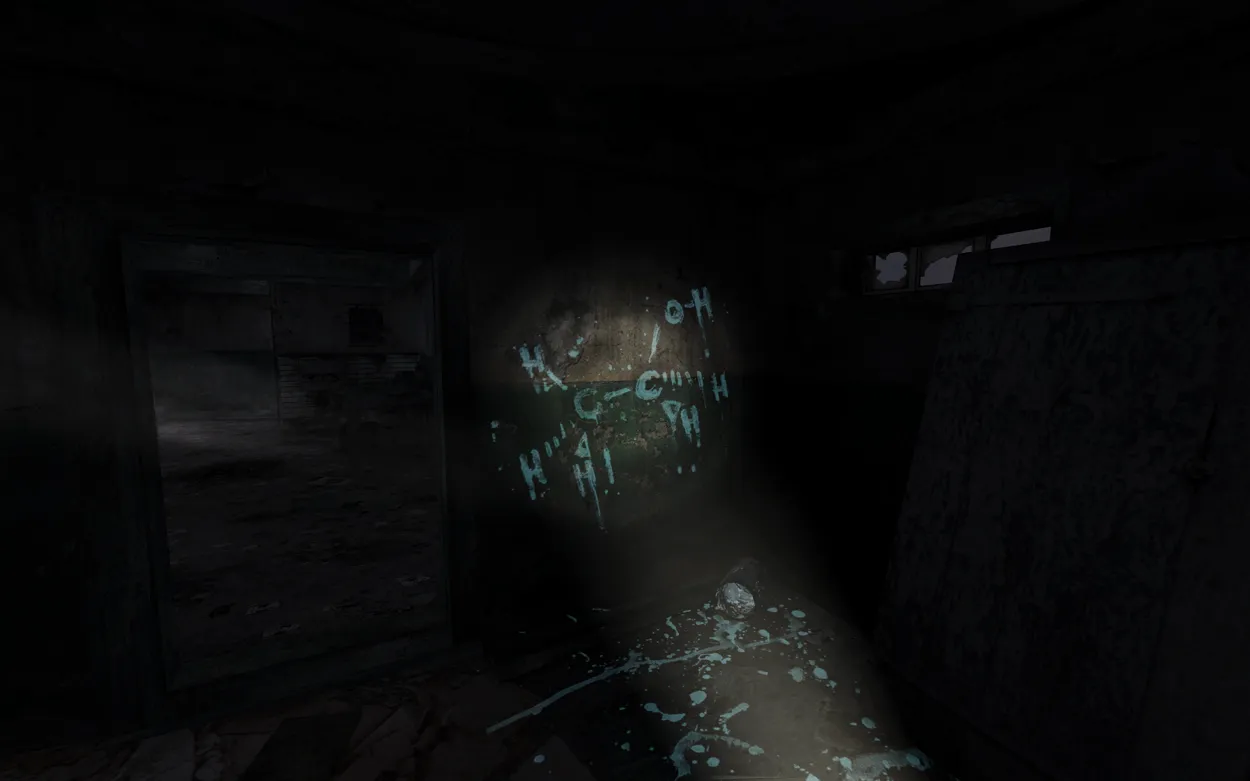

As the narrator told his story, moving past painted outlines of alcohol compounds, I thought about what this story must look like from Esther’s perspective. One in four women experience intimate partner violence , and while this man killing his wife in a drunk driving accident doesn’t fit into that category, it still very much fits into the general idea that the most dangerous person in a woman’s life statistically is the man she shares her life with. As I listened to this man explain without explaining, dance around the reality of what he’d done, I thought about the finality for Esther, how she had trusted this man enough to get in a car with him, and how he could now no longer even remember where he’d killed her. The story of this woman’s death had ceased to be her own, and had instead been co-opted by the man who killed her.

And I stand behind him, directing him up cliffsides, listening to him talk about the book he’s been reading, and helping him explore the island before his demise. I listened to the story of the violence he’d exacted on Esther, and I just wanted it to end. I wanted him to get to his destination, not because I wanted his death, but because I no longer wanted any part of this story he’d made his own.

Cool.

Cool.

A walking simulator only works when its story does. There needs to be some reason for the player to absorb themselves in the story and world, and want to stay invested. A game like Firewatch or What Remains of Edith Finch works because their stories are compelling, and drive the player forward, wanting to know more. Games like Abzu , 35MM , and Arctico do a fantastic job of building a world that’s worth exploring and making the games themselves an experience. Dear Esther, with its landscapes and slow exploration of seaside cliffs and caves, initially seems like it could be following this school of thought, until that realisation of who the narrator is sinks in. There is no redemption from the story being told, no way to salvage an enjoyable experience. Without something for me to get lost in, there’s nothing holding me to the game, and so, I just wanted it to end.

Mmmm…cave…

Mmmm…cave…

There are ways to make a morally problematic protagonist interesting and worth engaging with. The previously mentioned Firewatch is a good example of this, though the protagonists are very different people. The protagonist in Firewatch made the decision to leave his sick wife and take some time to recover his mental health by spending time in a fire tower. There, he reflects on his actions, and what future he wants to build. His past decisions are loudly unspoken, and when they are discussed, there is an almost catharsis to that discussion. It is good to hear him consider what he’s done and what he’ll do in the future, and to consider the cost of his actions.

Similarly, most RPGs provide a way for the player to be some form of reprehensible, if they choose to be so. Cyberpunk 2077 , for example, presents the player with the ability to be a casual jerk in a traditional RPG way, but also allows for their backstory and ending to play directly into the overall dystopia of the setting. The key here, though, is that these are choices the player makes. The player chooses to engage with the seedier elements of the setting and forge a character into who they are, rather than having that forced upon them.

This is the rub of Dear Esther. There is no catharsis for the player in the protagonist’s self-reflection. There is no choice for the player. They are forced to become this person, to hear this man, and to participate in a final act of destruction. There is nothing liberating about it, nothing cathartic about the moment of descent. There is only the knowledge that violence begets violence, trauma begets trauma, and the cycle is forged again and again and again.

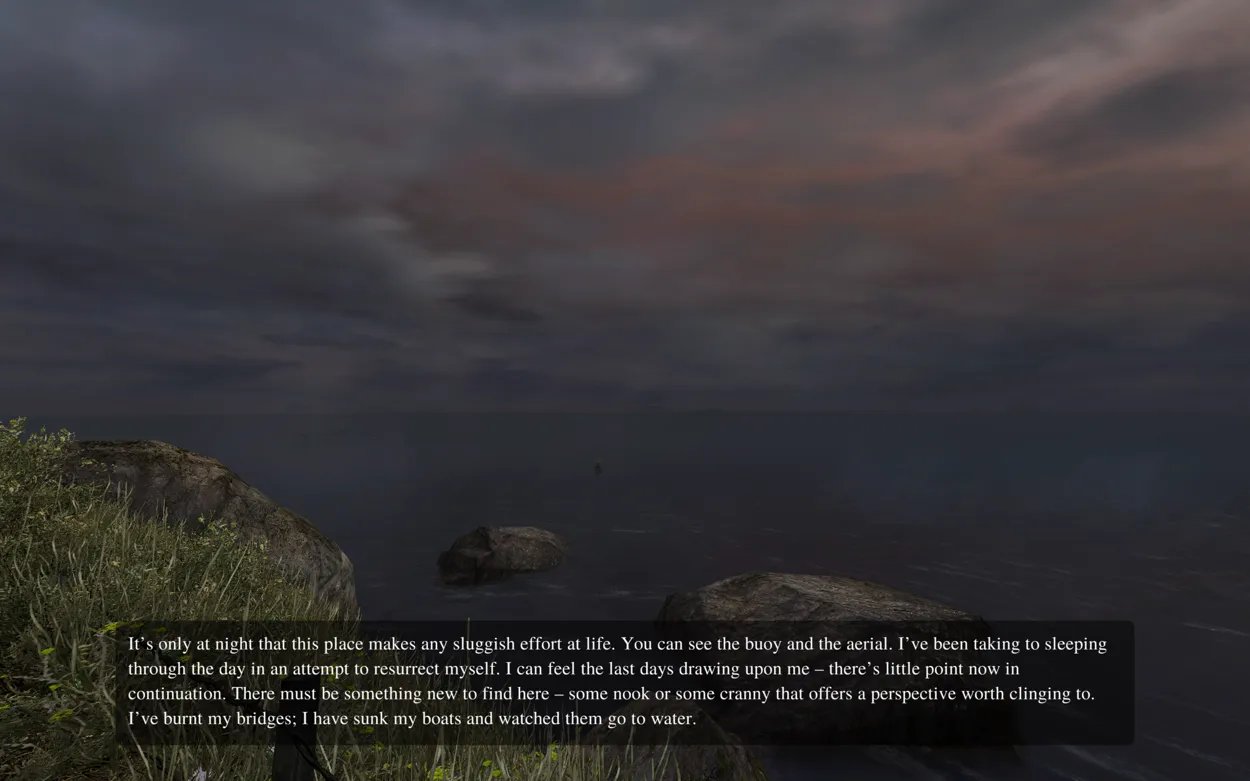

I feel like the writer had one good idea here, but needed, like, a hundred more words to squeeze out of that line.

I feel like the writer had one good idea here, but needed, like, a hundred more words to squeeze out of that line.

The final bit of horror comes from how the narrator engages with Esther after her death. Much as there is no catharsis or relief for the player, there is no relief for Esther either. I, again, pictured her throughout the game, this ultimate violence having been exacted upon her by someone she trusted, and then to be subjected to his letters until his own death. She is dead, of course, and death makes it difficult to receive a letter, but in the narrative of the game, at least, she has some sort of letter. I was struck, thinking about that spirit being bombarded with this man’s thoughts and emotions, and the lack of escape or peace from any of it.

These thoughts about Esther likely hit me harder than than other players. I’ve been stalked. I’ve been harassed. I’m a sexual assault survivor, and I know what it is to receive unwanted affection from someone who has hurt you deeply. As I heard these snippets of the narrator’s letters, I thought about the men who have hurt me. I thought about their centring of themselves in the narrative of my trauma, and how I will never escape from beneath the shadow of what’s been done to me.

I am alive, and Esther is not, but still, I see myself in her.

sisyphus sisyphus

sisyphus sisyphus

This is, of course, not the only potential reading of Dear Esther. The writing is nonsensical enough that there are other - or no - coherent readings, and people will find what they choose to find in a piece, based on the lens of their own experiences. For me, though, this is a game about a man who has and will continue to commit horrors, and does so without recognising what it is he’s done. However beautiful the landscapes, all I hear and see is this man, marching to a self-imposed doom, brought there by his own acts of violence.

And I’m forced to join him. I have no choice but to have this man act out his will upon me. My failure was that I trusted this situation in the first place.

Developer: The Chinese Room

Genre: Walking Simulator

Year: 2012

Country: United Kingdom

Language: English

Play Time: 1 Hour

Youtube: https://youtu.be/0US9akTsiqg