Death Squared

To understand Death Squared, we need to talk about Portal.

Portal is a puzzle platformer released in 2007. It centres on a woman named Chell trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of “tests” with a malevolent AI named GLaDOS. Over time, Chell reveals more and more of the story of what happened in the Aperture Science lab, and - spoilers - defeats GLaDOS and escapes to the great cake in the sky. Portal tells its story through both never-before-seen mechanics and the copious use of dark humour. Throughout the game, GLaDOS comments on the player’s performance, the setting, and her thoughts on what’s going on. These comments are delivered in a flat, android voice that nevertheless contains a fair bit of emotion and soul, albeit not a soul that cares about you or your well-being. GLaDOS is a fantastic antagonist, with enough personality to make the player want to prove they can beat her expectations, but an alien enough personality that there is no empathising with her or her situation. She is a force of nature, and it is up to the player to stop her.

I would like to hide in my corner forever, please and thank you.

I would like to hide in my corner forever, please and thank you.

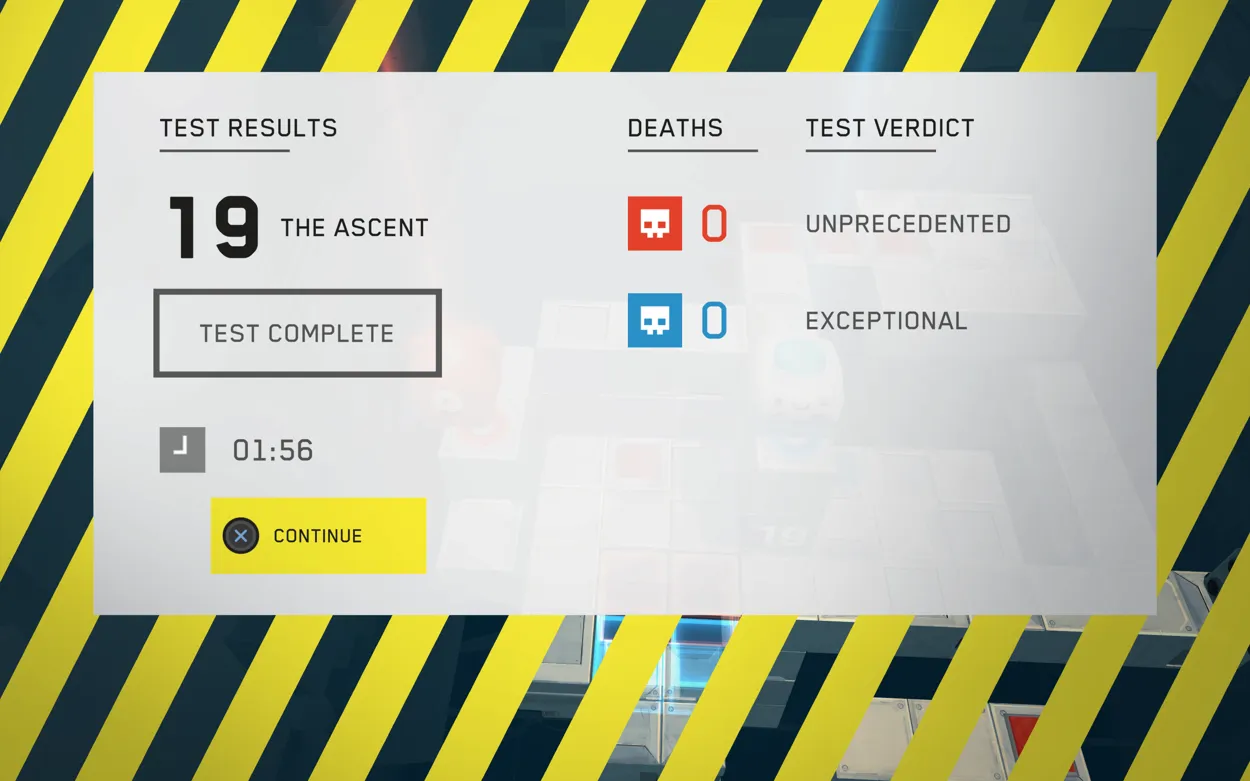

I bring up Portal both because of its massive impact on puzzle games and gaming as a whole, but also because it is clearly a very direct inspiration for Death Squared. While not the same type of puzzle platformer as Portal, Death Squared is clearly trying to succeed by hitting the same sorts of buttons as Portal. In Death Squared, players control a cube, directing it through a puzzle maze towards a colourful circle. As they do so, a test manager commentates on their actions, cheering when the players solve the puzzle quickly or without deaths, and criticising when they take a while, or die often. The commentary also provides an insight into the world these cubes inhabit. The world of Death Squared is a corpo-dystopia, where capitalism is the simultaneous horror and security blanket, and where pointless jobs are the only real possibility for survival. There is a quiet background horror that, while it doesn’t often intrude into the puzzles themselves, still establishes a sense of utter pointlessness to the task the cubes are engaged in, and that it’s up to the player to find meaning within them.

Ordinarily, this would be fine. There are lots of puzzle games where the satisfaction of solving the puzzle is enough to keep the player motivated. Indeed, I’d argue that, for most puzzle games, it’s reasonable to expect that the player will be happy solving puzzles and doesn’t necessarily need some external judgement. The difference with Death Squared, though, is that it not only doesn’t trust that the player will be happy solving the puzzle, it provides negative reinforcement to motivate the player to do better. The game negs the player constantly, and in so doing, strips away the joy of solving puzzles, replacing it with a sense of insecurity and loathing.

I think I did pretty well. David disagreed.

I think I did pretty well. David disagreed.

To be clear, there’s nothing inherently wrong with a game negging its players. A friendly ribbing can instil a satisfying sense of camaraderie between players, as well as creating a setting that feels more alive and interesting to engage with. The difference with Death Squared, however, is in that there is no gentle ribbing. There is a negging from a commentator whose approval I have no interest in garnering, because his approval isn’t worth anything.

Death Squared’s GLaDOS is named David, and is paired with an AI named IRIS. David’s job is to test AIs to see how well they’ll perform in various real-world tasks. David, the game makes clear, is abysmal at his job, and serves more as a human rubber stamper for IRIS than any independent tester. He steals lunches, shows up to work drunk, and is a wholly unpleasant person. David’s job performance is dependent on how well these test cubes do, but I, as a cube, have very little incentive to see that David gets a good review. If anything, I want David to reap the consequences of his poor job performance. David, however, would prefer to receive a good review, and so constantly belittles and insults the cubes’ performances. It rapidly becomes grating and unpleasant.

Death Squared looked at GLaDOS’s commentary in Portal, then missed everything that made GLaDOS a compelling adversary. Instead of creating something that the player wanted to strive against, they created an adversary who is only ambiguously an adversary. That David benefits when I do well makes the game feel Sisyphean. I will never succeed in giving this man the comeuppance he so richly deserves, so why should I bother? David is every obnoxious coworker you have ever had, invading the space that is supposed to cathartic and fun with the smug self-assuredness of knowing there is nothing you can do to get rid of him.

I feel like one of these cubes is having more fun than the other.

I feel like one of these cubes is having more fun than the other.

What makes the negging worse, however, is the fact that, while the mazes themselves are well designed, they are also themselves spiteful little hate balls. On more levels than I care to count, I got to the final goal and stepped on, only for spikes to pop up, killing my partner and causing me to need to restart the level. Death traps abound in arbitrary places and ways, and even when I thought I could predict them, one would always somehow manage to surprise me.

It’s when these arbitrary death traps are placed in a puzzle with awkward controls and views, though, that they just become unbearable. The cubes always feel a little too big for the spaces they’re meant to occupy, making the precise movements sometimes needed to solve the puzzles or avoid the spikes difficult to get right. This is coupled with a semi-topdown view that obscures the outlines of certain squares or the complete layout of the puzzle, making it difficult to gauge placement. Sometimes, I believed I was on the correct square, only for spikes to pop up, showing I’d never been fully on the square in the first place, and had no way to see it.

These spatial issues are further compounded by the fact that the characters solving the puzzle have momentum. While momentum, on the surface, doesn’t sound it should be an issue, it creates a space in which anything but the most delicate movements becomes a bit of a guessing game as to whether or not you’ll end up where you intended to end up. Quite often, I found myself happily zooming off an edge and needing to restart a puzzle because I didn’t accurately guess how much momentum I would have when I finally arrived at my destination. This decision to include momentum becomes especially baffling when you consider that there is no reason to include it. There is no benefit to it, no puzzle that requires it to solve. It is, much like the spikes that pop up at the very end of the level, a decision that just feels malicious.

And throughout it all, there is David, whining “Don’t mess this up.”

I should fit, and yet, I do not.

I should fit, and yet, I do not.

Death Squared is a dystopian game, both in the setting it presents and the reasons for these cubes to be undergoing this hell, but also in its underlying philosophy. It understands puzzle design well enough to construct some legitimately interesting and fun puzzles, but does not fundamentally understand what makes a puzzle game itself fun to play and complete. It strips the soul from these puzzles, replacing them with a constant, whining reminder of the coworker we would all like to forget, and a spirit of malicious spite. It’s not fun, and no amount of cute faces or bright colours can redeem it.

Developer: Smg Studio

Genre: Puzzle

Year: 2017

Country: Australia

Language: English

Play Time: 6 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/IJ8VDcNI538