Across The Obelisk

When I was growing up, I played a lot of collectible card games. I had binders full of hundreds of Pokemon cards that I accumulated from other kids at school, then a smaller binder of Yu-Gi-Oh cards, and then massive boxes of Magic: The Gathering cards. I wasn’t necessarily good at any of these games, but I spent a lot of time with them. At any given MTG draft, I’d be huddled over my new cards, piecing together their mechanics and puzzling through how best to make them into something unstoppable. Then, of course, I’d lose in the first round of the tournament, but that was never the point. No, the point was looking at disparate pieces and figuring out how to put them together into something I could have fun with.

I no longer have those boxes and binders. I suspect my parents either tossed them out or left them to rot in an attic after I moved out. I do, however, have an entire genre of video games designed to appeal specifically to people like me, whose childhoods were built around card mechanics, and who just want to recapture some of that nostalgia for a few hours. These are deck-builders, and I love them.

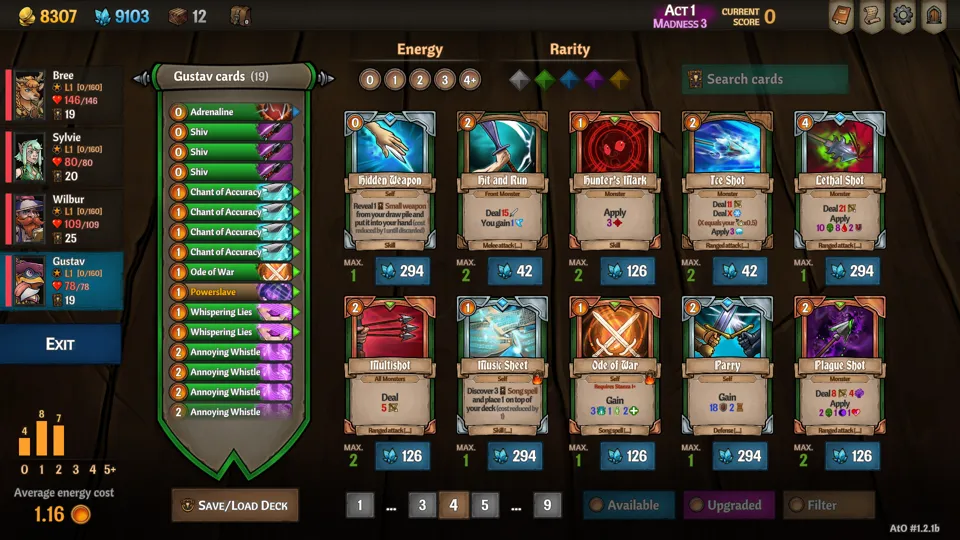

So…many…cards….

So…many…cards….

Across the Obelisk is a roguelite, deck-builder RPG. You play as a party of four characters - either in single or multi-player, and I’ll discuss both - on a quest to save the princess and rescue the realm from oblivion. Along the way, the party must fight bosses, face encounters, and have a grand time learning and growing as a team.

Though it is a deck-builder RPG, it is a very different style deck-builder RPG than Black Book specifically because of the balance it chooses to strike between story and mechanics. Black Book puts a heavy focus on its story, with mechanics being an almost secondary (but still critical) consideration. Across the Obelisk is a much more pure deck-builder, with the story being more flavour than the actual driving force of the game. Your goal as a player is not to uncover why Faeborg the dragon has frozen the elf forest, or to have a deep heartfelt conversation with Yogger about trauma and the Wolf Wars. Your role as a player is to get the party from the opening village to the ending cinematic using as many fun card combos as you can.

I

call this combo “oops, no healer.”

I

call this combo “oops, no healer.”

Across the Obelisk isn’t unique in its genre. Deck-builders have their well-established and much-loved niche in the gaming industry, and they come in a broad variety of shapes and sizes. Across the Obelisk’s contribution to the genre is less its card mechanics, but rather, its party mechanics and how those factor into a particular style of play. Across the Obelisk can be played either single player (with one player controlling four characters) or multi-player (with each player controlling one or more characters). In addition to each individual character’s deck needing to be optimised, each character needs to be optimised to fit within the party dynamics. This has the potential to create interesting, highly optimised parties when playing as a single player, or utter madness when playing multi-player.

However, it’s in these optimisation mechanics that the flaws of the game also start to appear. For many deck-builders, the replayability of the game centers on its draft mechanics, and the idea that any given run will differ from any other because of a difference in the draft. As an example, at the end of each combat in Across the Obelisk, players receive card rewards. These rewards are random, and so, in theory, the deck the player builds should also be more randomised. Similarly, the equipment the player collects over the course of the game enhances the deck, and is also randomly distributed. This, again, should lead to each run being different, since the raw resources with which a deck is crafted are different. In practice, however, the randomness is disrupted by the rest point between levels - the town.

Such

a sinister town, with its bright colours and friendly appearance

Such

a sinister town, with its bright colours and friendly appearance

Each town contains a mechanic to remove cards (the church), a mechanic to upgrade cards (the shrine), a mechanic to create cards (the forge), and a mechanic to buy equipment (the shop). Players can gain currency for these buildings either over the course of their adventures, or through finishing the game and carrying over their loot from that run. While some equipment is limited to specific encounters, the majority of equipment and cards can be crafted or bought in the towns. From the outset, players can craft their decks into whatever they want it to be, and can potentially have the same deck every time. Indeed, the game itself has a feature where you can save and reload certain decks in order to use them again. The randomness that is the hallmark of the replayability of other deck-builders doesn’t exist in Across the Obelisk. Instead, Across the Obelisk is an optimiser with pre-inputted conditions. The challenge isn’t to make the best of what you’re given, but rather, to figure out how to beat the game before you’ve even played.

Sylvie.

You beat the game with Sylvie.

Sylvie.

You beat the game with Sylvie.

To be fair, there’s nothing wrong with an optimisation game. Watching damage numbers climb into the stratosphere is immensely satisfying, as is the recognition that whatever combo you’ve chosen to build is successful. I don’t point out that Across the Obelisk is more about optimisation than about drafting as a slight - each game approaches the question of how to tell the story it wants to tell in its own way - but rather to point out a reality of how well-designed this game actually is.

When the core of a game is optimisation, a game becomes more or less solvable. While there might be variation in any given run, the same build, once successful, ought to continue to be successful on future runs. This defeats the purpose of being a roguelite or of having drafting mechanics. Once the player has solved the game, there’s no reason for them to try different builds or even to replay the game. It’s solved. They will win every time. Game over.

Across the Obelisk is fascinating in that it successfully threads the needle between optimisation and replayability. It’s possible to conceptually have the perfect build and to win with it every time. However, if you do so, you miss out on the other potential builds that the wealth of characters and their unique builds open for you.

I

love the little random dice. It makes every run spicy.

I

love the little random dice. It makes every run spicy.

In providing mechanics to optimise, Across the Obelisk also provides reasons not to and continuously asks the player to consider the wide variety of options available to them. I could win if I play Sylvie every time, sure, but how does her build combine with those around her? Are there ways to build new and better combos that haven’t been found yet? Across the Obelisk asks not only for optimisation, but for a mindset of constant improvement and exploration of the possibilities. It may not be a perfect drafting game mechanically, but the idea of exploration and experimentation that undergirds drafting also dwells in the heart of Across the Obelisk. Combined with the ability to have four different players, each building their own perfect deck, and the possibility of discovering something new on each run drives the player to play and replay again.

In addition to the primary mode providing a motivation to experiment, Across the Obelisk also has a separate second mode that is more in line with traditional drafting mechanics. This mode provides a true random experience, with enemies, locations, and players’ cards entirely randomly generated.

That

world was definitely broken when I got here.

That

world was definitely broken when I got here.

Though the original, story-driven mode does a good job of being engaging, I prefer this second mode. Obelisk mode requires the player to think creatively and make do with the build they are given rather than a more optimised one. While it leans far in the opposite direction of the original mode in perhaps giving the player too few options, the thrill of being forced to make do with a build held together with shoestring and duct tape is delightful, and keeps me coming back for another run.

Across the Obelisk is not perfect. It can have a steep learning curve for new players, especially as abilities flash across the screen, unexplained and difficult to follow. However, once a player understands (more or less) what’s happening around them, the game becomes an orchard. Each playthrough potentially bears fruit, or potentially doesn’t; it’s up to the player and their creativity and sense of exploration to figure it out.

Developer: Dreamsite Games

Genre: Roguelite, Deck-Builder

Year: 2021

Country: Spain

Language: English

Play Time: 2-3 Hours/Run

Youtube: