Beasts Of Maravilla Island

Between this game, Alba , and Beyond Good and Evil , I’ve been thinking about the photography and what photography is actually expected to be. It may seem straightforward, that we expect a photograph to capture some moment or place and preserve it, but I’d argue that’s not what the vast majority of photography is doing. What photography captures is some element of reality shaped into narrative by the entity holding the camera. The act of deciding to capture a particular moment in a particular way already shifts it from any kind of objective reality into the realm of the subjective and already forms part of the narrative. There is a reason the photographer chose this place, this moment, and this angle. That reason becomes part of the photograph as much as the subject or composition. Photography isn’t an objective lens. By its very nature, it can’t be.

The role of photography is a narrative one, presenting a version of reality that we choose to capture and present. The question I think photography in games is asking, though, is what the expectation is for that created narrative. When a narrative is created through photography, who is that narrative for? Is it expected to be shared with others, or is it just for ourselves? If I take a screenshot, am I doing so with the expectation that I’ll show it to someone else, or is the picture just for me?

It’s in how this question is answered and the overall philosophy of the purpose of photography that start to feed into how I feel about Beasts of Maravilla Island.

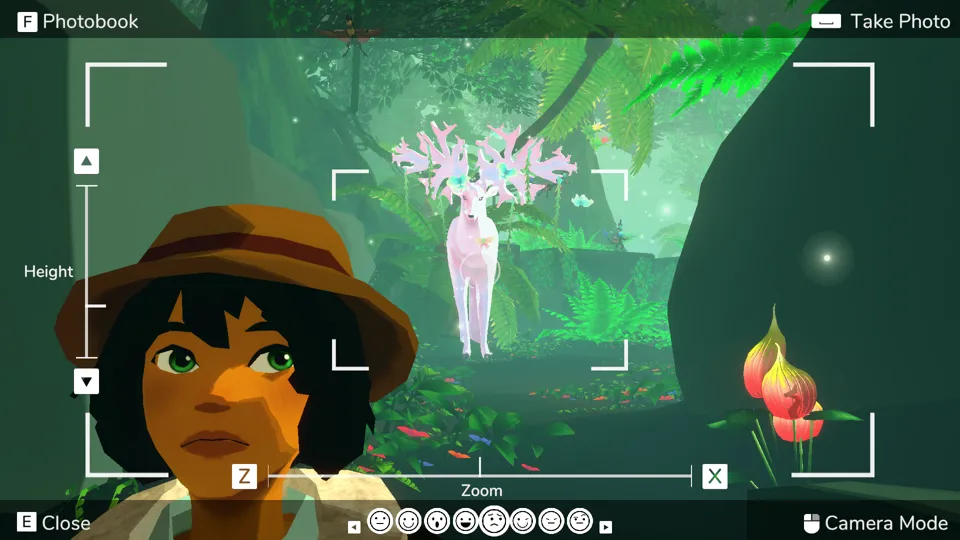

It’s important to take pictures like this for when they inevitably make a true crime podcast about your disappearance into the jungle.

It’s important to take pictures like this for when they inevitably make a true crime podcast about your disappearance into the jungle.

Beasts of Maravilla Island is an adventure photography game. You play as an explorer, exploring and documenting the flora and fauna of the fantastical Maravilla Island. Equipped with a camera and a guidebook, you wander the island, documenting what you find, and learning more about this magical place.

For a game about wildlife photography, the graphics and controls are surprisingly clunky. Even setting aside the limitations of me playing on touchpad, on multiple occasions, I found the camera sitting in the middle of my character’s head, or my character refusing to climb or leave a tree, or the controls to move the camera too tacky for me to accurately capture a photo I wanted. As much as the world wanted me to photograph it, the game’s controls made that difficult throughout, making engaging with the world frustrating.

Maravilla Island, to be clear, is a world that very much wants to be photographed, though I’d argue the underlying philosophy behind why it wants to be photographed and how it expects the player to understand photography provide an even greater frustration than sticky controls or graphical glitches.

The peeping tom pictures are also important for the true crime crowd.

The peeping tom pictures are also important for the true crime crowd.

There are two main purposes that spring to mind when thinking about what photography is meant to do, and two primary reasons why someone might choose to take a picture. A picture can be used to focus on the details of a place, on some element or combination of elements that add beauty or character to the place or moment. Photography in this context trains the photographer to let the camera augment reality and create a greater sense of immersion. Rather than just looking at the world, the camera asks the photographer to see it, to notice it, and to think about what they’re observing around them. This is what a game like Alba encourages its players to do, and what I’d argue my own photography has done for me. The world needs to be seen with a more critical and more observant eye, and so the photographer starts to see everything.

A picture can also be used to share a particular experience with others. When this is the primary goal of a photograph, the act of existing in the moment and noticing the details becomes subsumed by consideration of the narrative being crafted. Rather than being encouraged to be immersed in the world, the photographer is instead thinking about the act of sharing it - where they’ll share it, how they’ll caption it, all these elements that are not the composition and world around them. Photography becomes a forward-thinking activity, and in so doing, ceases to encourage the deep observation that photography for its own sake encourages, and instead plays a secondary role to the creation of narrative.

When I think about photography as subservient to the act of narrative creation, I inevitably think about the commercialisation of art, and the demand that art can’t exist on its own merits. The act of being an artist and trying to have that art seen by someone else isn’t about whether a particular piece of art is good. Rather, whether art succeeds in being seen is entirely dependent on the artist’s ability to market it, to generate a narrative that others can buy into, and understand how to pitch that narrative in such a way that it hooks the intended audience. Art takes a backseat to marketing and to capitalism. That first consideration, of art for the sake of greater immersion, takes a backseat to the second, of art as a tool for narrative. What we’re left with is art that exists solely to sell itself.

We’re left with social media influencers and the false narratives propped up by a photographic facade.

This is where the true crimers will find a fun portmanteau to refer to my disappearance, and where the real arguing will begin.

This is where the true crimers will find a fun portmanteau to refer to my disappearance, and where the real arguing will begin.

In trying to market and sell my book , I’ve consistently run into the hurdle that the knowledge and information in the book is not enough to justify its existence. What’s asked of me in every interview and event is to sell not the book, but myself and my authenticity. On the one hand, it’s understandable. A non-fiction book is more credible when the author is a known expert in the field, and I am an expert in what I’ve written about. On the other hand, what’s being asked for is not the information I’ve already given. It’s the little prying questions, rubbing at the edges of the story I present, probing and hoping to dig up more. At the point that I choose to share anything publicly, I’m asked to share everything publicly. I cease to be a person, and become an object of fascination.

In that light, I create a narrative. I practice the words in my head before every interview, telling enough of a story to try to tamp down those prying barbs, while still feeding enough of a version of myself to the asker that they’ll be satisfied. I create this persona to stand in front of the camera and repeat the same story over and over.

My name is Janneke Parrish. I am an activist, and here is my story. My name is Janneke Parrish. I am an activist, and here is my story. My name is Janneke Parrish. I am an activist, and here is my story.

The narrative isn’t for me. I don’t tell my story for my own sake anymore. I tell it for the sake of the audience, presenting a version of me for them to believe in, and hoping that the facade is sufficiently well-crafted that no one will look any deeper. My life story, my self, becomes the product, and I sell it as best I can.

This idea of reality being a carefully curated fiction lies at the heart of Beasts of Maravilla Island. Beyond the obvious parallel of the photographer choosing which picture to put in her scrapbook, the world itself feels inauthentic, carefully posed and curated to provide a specific set of images, but with no real authenticity to it. The purpose of the world is to exist for the photographer. It does not exist beyond what she sees. It is vibes, and it is a crafted narrative.

Aha! The true culprit was there all along!

Aha! The true culprit was there all along!

Beasts of Maravilla Island is the Van Gogh Experience, the Instagram-art-version of photography games. If approached with a particular purpose, it does exactly what it’s supposed to do, but peel back the carefully curated narrative, and the reality of what it is comes tumbling out. This is a world that offers no freedom of expression, but does the work of photography for you. It carefully curates each scene to present a good photo, then shuttles you along to the next, leaving no time or space for contemplation or admiration. The point of the photo is the photo, not any deeper observation about its subject or its composition. There is no room for thought, and no expectation that there would be thought. There are creatures posing, scenes cultivated, and you, moving mindlessly through a story already told on your behalf.

It is a photo to be shared, nothing more.

Developer: Banana Bird Studios

Genre: Adventure, Photography

Year: 2021

Country: United States

Language: English

Play Time: 2-3 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/la3n1foDiCs