Cities In Motion

I’ve written at length about city builders and the ethos they promote, of growth without cost, and of the idea of expansion for its own sake being the ultimate good. In some ways, a transport simulator echoes this sentiment, with its driving ethos being one of expanding and upgrading, of growing and growing to serve as many people as possible. At the same time, it also displays the opposite sentiment, with growth needing to be carefully measured and considered, and with every expansion having a cost. In Cities in Motion specifically, the ethos of the game is explicitly in opposition to the growth without cost mentality of its sister game, Cities: Skylines. Here, the motivation for building these expansive transit networks is to limit the scourge of cars, and yet, it’s also to support the growing city. In some ways, Cities in Motion seems to straddle the line between considering the role transit plays in the horror that is a city builder, and being the horror in and of itself.

The question I was left with as I played it, however, became less one of ethos, and more one of trying to understand the world Cities in Motion inhabits. What is this world, so centered on transit, and yet so unable to succeed at that goal? What is this place, and why does it insist on being the way that it is?

And who is airplane?

And who is airplane?

Cities in Motion bills itself as a transport simulator, though I would argue that’s not actually what it is. The player manages the transit networks for four cities - Berlin, Helsinki, Amsterdam, and Vienna - helping them grow, navigate the city, and become an intrinsic part of the city’s landscape. There is both a campaign and sandbox mode, though I focused on the campaign. The campaign relies on a series of missions in a particular city, providing rewards and unlocks as the player progresses.

The meat of the game lies in how it actually simulates a transportation network. The game provides a variety of transportation methods, from the always-boring bus to the extremely exciting helicopter taxi. What combination of these a player chooses to utilise is entirely up to them, and indeed, half the puzzle is figuring out what transport type is the most appropriate for a given situation.

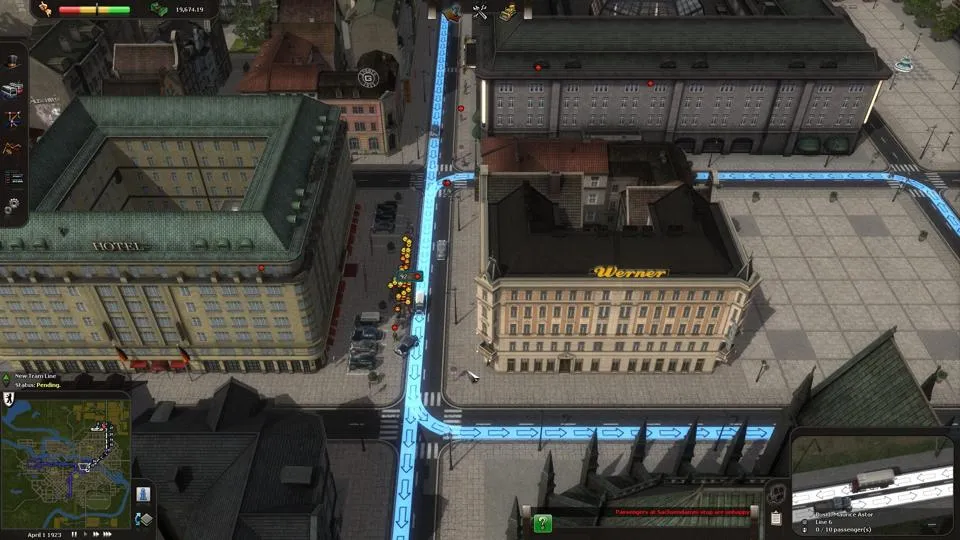

I should probably build something here, at least.

I should probably build something here, at least.

My use of the word “puzzle” is deliberate. Cities in Motion bills itself as a transportation simulator, but it is brutally, crushingly difficult if played as one. This is not a game that allows for creativity or flexibility. It is a game that envisions each city as a puzzle with a set of correct answers. When played as part of the campaign, where options are limited, that set of answers diminishes considerably, but with no real indication to the player that that’s what’s happened. I tried the first scenario several times, and always ended up the same - bankrupt and staring down the barrel of a thousand angry passengers. It may be there is something I’m missing, but I think it’s more likely that this is a game with an idea of the correct answer, and the expectation that the player will understand that as well. It looks like a transportation simulator or a city builder, but it plays like a puzzle game or a point and click.

This isn’t necessarily a problem. There is plenty of room for treating the act of transporting people from one place to another as a puzzle and designing a game to simulate that. That is exactly what Mini Metro does, and Mini Metro succeeds fabulously at that goal. The issue with Cities in Motion is less that it’s a puzzle, and more that it pretends it isn’t. By offering up an entire city and a variety of toys to apply to it, it invites the player’s creativity and imagination. It beckons them in, before grabbing them, mugging them, and shoving them back out the door to wonder what exactly just happened.

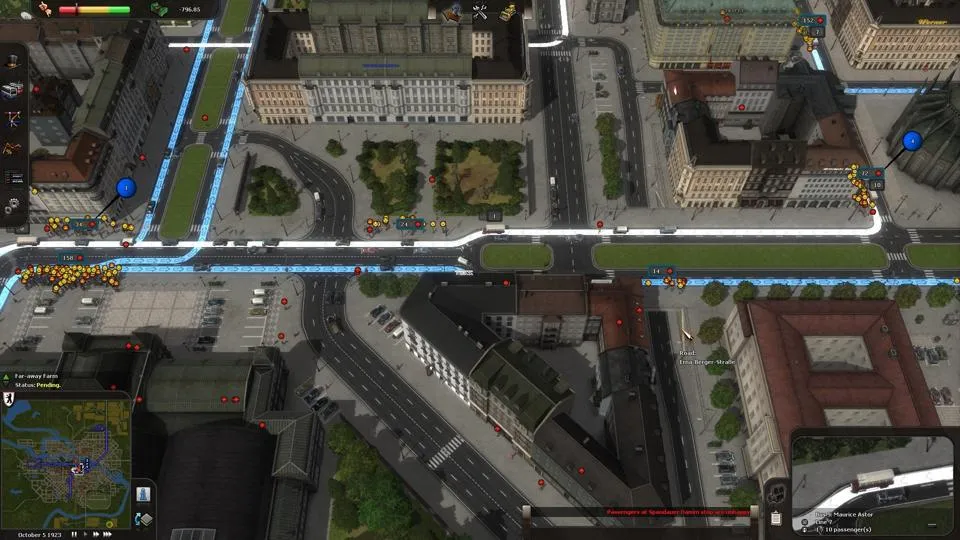

Werner is big mad

Werner is big mad

There are a lot of reasons why the transportation systems presented in Cities in Motion don’t work. The most basic transportation method - buses - clog traffic, and thus delay themselves by fulfilling their most essential function. The only way to improve their service is to add more, which only increases the delays. Other transportation methods are more efficient, but track or station placement is finnicky, and tracks may need to be built and demolished repeatedly to make things fit. The game has intricate economic mechanics which, if not monitored, lead to a rapid bankruptcy, but there is no real way to automatically keep track until everything begins to collapse. If the system does start to turn a profit, it’s on the backs of larger transportation systems, which can’t be built until much later in the game.

All of these elements make sense within the context of a transportation simulator, but again, it is the brutal and punishing difficulty of balancing it all that leads to an unfun experience. Rather than having fun sketching out routes I thought were efficient, I stared at the passengers refusing to board the bus, and getting increasingly angry that they weren’t on the bus. I watched my little streetcars trundle along, making no money, but having a lovely time dinging their little bells.

And I watched the people accumulate at stops, hundreds of them, waiting to board a bus that could carry ten at a time, and I wondered what exactly they expected from me. As my reputation plummeted, I stared at them. Did they expect some miraculous system to spring wholly from the earth, fully formed and ready to accommodate hundreds of people in an instant? Who were all these people, and why were they so angry that a bus that did not exist, that no one said existed, did not, in fact, exist?

Who are you?

Who are you?

It’s this that I keep coming back to when I think about Cities in Motion, this thought of what it’s trying to be. I would argue it’s a puzzle because it expects a specific solution, but I would also argue its ethos is that of a city builder. It expects everything, and punishes when those aren’t fulfilled. The people of Cities in Motion have no patience, no tolerance, no humanity within them, and yet we are expected to design human systems for them. We apply our human logic to a world lacking it, and are baffled when it does not respond in kind. It is a brutal game, asking everything, and yielding nothing in return.

The map is pretty, though.

Developer: Colossal Order

Genre: Simulation

Year: 2011

Country: Finland

Language: English

Play Time: 25-40 Hours

Youtube: