Vegan Žemlovka

Ingredients

1 stale baguette

2 apples, peeled and sliced

1/2 cup (100g) raisins

2/3 cup (160g) vegan butter

2/3 cup (125g) vegan creme fraiche

3/4 cup (190g) applesauce

1 2/3 cup (400ml) non-dairy milk

1/2 cup (90g) sugar

1 tsp vanilla

1 tsp cinnamon

Powdered sugar

Instructions

- Preheat the oven to 370F (190C). Rub the bottom of a casserole dish with butter, and sprinkle with crumbled bits of baguette.\

- Combine the milk, creme fraiche, applesauce, sugar, and vanilla, mixing until smooth. \

- Cut the baguette into slices ~1cm (1/2 inch) in width. Soak the baguette slices in the milk mixture until the milk is absorbed, but the bread isn't falling apart (~10 minutes, depending on how stale the bread is. The staler the bread, the longer the soak). \

- Create a layer of soaked bread in the bottom of the casserole dish. Add a layer of apples, raisins, and cinnamon. Top with the remaining bread and milk mixture, and press the bread down to create a topping for the apples. \

- Rub the top layer of bread with the remaining butter. \

- Bake for 45 minutes until golden. Serve warm and topped with powdered sugar.

A longer and more detailed description

Have you ever looked at French toast and thought “this could be more complicated, and topped with apples, and have some raisins tossed in there, and baked?”

Say no more.

Žemlovka is, fundamentally, the same concept as French toast. It’s the bits of bread and fruit a Czech peasant found in their basement and decided to make edible by mixing it with eggs and milk and prayers. In our case, we’ll be substituting out the eggs and milk, but it never hurts to leave in the prayers to the culinary gods for yet another successful experiment.

We’ll start by making our milk mixture. Combine your cream, milk, applesauce, sugar, and vanilla into a lovely bowl of goodness and give it a nice mixy mix. Once it’s mixed, channel your inner peasant and grab the baguette you’d forgotten about in the back of your pantry in preparation for this dish, slice it into slices, and toss the slices into the milk. Then, promptly ignore them. It is the way of your people.

While the bread is soaking, peel, core, and chop your apples into lovely slices. If you have any remaining crumbs from hacking your baguette into pieces, dump that into a casserole dish. They’ll make a nice base for this dish, and you get to feel good about not wasting anything.

Remove the bread from the milk, creating a layer of bread in the bottom of the casserole dish. Once there’s a complete layer, add your apples, raisins, and cinnamon in a nice, pretty layer. Add the rest of the bread on top, pushing down on it with a fork so it makes a squelchy sound. If the sound is insufficiently squelchy, feel free to add the rest of the milk mixture to the dish. If it’s unpleasantly squelchy, you’ve done it right. Go you!

Pop your casserole dish in the oven for forty-five minutes, then wander off to do something else. You could, for example, go read other entries on this blog, now that I’m remembering to migrate them over from the old site! You could check out some of my other writing! Or you could stare into the abyss and pray, pray that it never stares back.

Ding! There’s the oven! Retrieve your lovely dessert, serving it warm and topping it with powdered sugar. Dobrou chuť!

Substitutions and Suggestions

For the raisins: You don’t have to make this with raisins. You can make it with any raisin-adjacent fruit or no raisins at all, if you hate yourself. You can also pre-soak the raisins in rum if you want to make something truly delightful, or you can forget to do that, like I did.

For the applesauce: Any egg replacer will work here. I chose applesauce because I had applesauce and I like what it does in baked dishes, but feel free to use what brings you joy.

For the creme fraiche: This is substituting in for heavy cream. If you have another vegan cream, feel free to use that. I, however, do not, so it is to the fancy French thing I turn.

For the baguette: You can use any stale white bread here, but baguettes make nice slices. Still, the point is to use what you have, so again, use what brings you joy.

What I changed to make it vegan

As stated in the description, this dish is naturally vegetarian. I made it vegan by swapping out the milk and eggs, and personally, I think it’s even better for it.

What to listen to while you make this

Can I interest you in the eternally wonderful genre of folkpunk and the band Tower of Dudes? Of course I can. Enjoy!

A bit of context for this dish

Czech cuisine is, like many of the central European cuisines we’ve discussed in this series, a meat-and-potatoes cuisine that has been heavily shaped by the influence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Czechia was, from the 19th century to its independence in the wake of WWI, a fundamental part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, providing huge amounts of industry and wealth to the empire. Prior to that, it had been a key part of the Holy Roman Empire, and it is from Czechia that we get the glorious word and concept of “defenestration.”

Like many of its neighbouring cuisines, Czech cuisine relies on meats, stews, potatoes, and cabbages, though with a unique twist that reflects its place within the empires around it. Czech cuisine is unique in how many sweet dishes it has, including as main courses. This tendency is a direct result of the influence of the Hapsburgs, the French chefs who followed them, and the coffeehouses that sprang up in their wake.

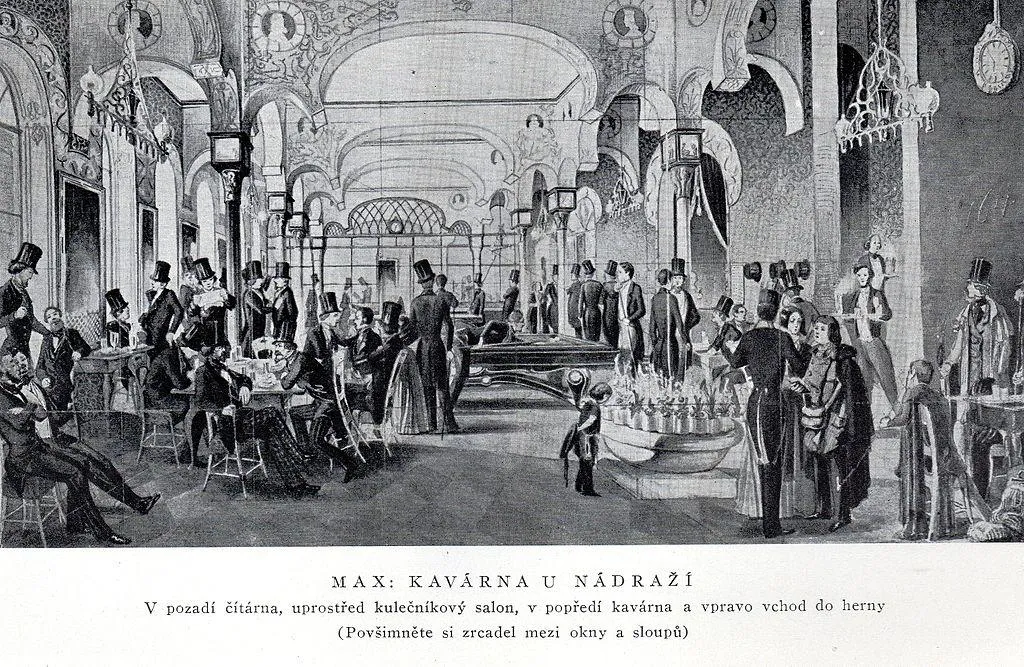

Prague is renowned for its coffeehouses. Much like Vienna, Czech coffeehouses are an institution, having grown up to fill the need for a social space in the the mid-19th century. Modelled off the coffeehouses of Vienna, Prague’s coffeehouses were havens of intellectual discussion, philosophical debate, and artistic banter. And, of course, coffee and pastries.

Many of the coffees served in these turn-of-the-century coffeehouses would be recognisable both to contemporary and modern visitors. Anytime someone argues the cappuccino is a modern invention, you can point them to the menu of the Cafe Continental and its advertisement of cappuccino, melange, Viennese coffee, hot chocolate, and chartreuse. Prague’s coffeehouses were a melting pot of every culture and people coming to the rapidly urbanising city in the heart of Europe.

While pastries and sweet dishes thrived in these coffeehouses, zemlovka thrived alongside, while also existing beyond them. The history of zemlovka can be traced back well past the introduction of coffee to Prague, and instead exists in the general central European culinary tradition. Recipes for zemlovka can be found in Roman cookbooks dating back to the 1st century CE, and it’s not unreasonable to believe the dish has been made for far longer than that. It has also, however, found its home in the modern institution of the coffeehouse, and become part of the fabric of the story of Czechia itself.

Not bad for some bits of apple and bread that someone found in the corner of their basement.