Vegan Kizaka

Ingredients

1 pound (500 g) spinach, chopped

1 onion, diced

2 tomatoes, chopped

1 green bell pepper, chopped

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 cup vegetable broth

1 cup peanut butter (roughly half a jar)

1.5 tablespoons peanuts

2 teaspoons pureed ginger (or one small finger, if you prefer fresh)

1 teaspoon chili powder

1 teaspoon red pepper flakes

Salt

Pepper

Oil

1 cup rice

Kitchen Equipment

A pan

A rice cooker

Instructions

- Set one cup of rice cooking in your rice cooker.

- Heat your oil over medium high heat. Once the oil is heated, saute the onions until translucent (3-5 minutes).

- Add the garlic and ginger, and cook for another minute.

- Add the tomatoes and bell pepper. Cook until the tomato begins to dissolve (~2 minutes).

- Add the peanut butter and peanuts, and stir until everything is coated.

- Add your greens, stir again, and cook for another 5 minutes.

- Add the vegetable broth and spices, and stir once again. Lower the heat and simmer until the liquid is mostly evaporated (5-7 minutes).

- Serve over rice.

A longer and more detailed description

Step-by-step instructions

Note that these instructions change based on what greens you’re using. Check the substitutions and suggestions section of the page for a wide array of ways to ignore everything I say completely and strike off on your own. It’s more fun that way.

Arrange most of your ingredients on your counter in an aesthetically pleasing way. Don’t arrange all of them, and don’t get the aesthetics entirely correct, as that would give you nothing to lament about when you’re writing this section of the recipe. No, get most of them, then kick yourself when your picture looks bad afterwards in a way that only makes sense to you.

This is my unaesthetic picture of food. I am ashamed to share it, but share it, I must.

This is my unaesthetic picture of food. I am ashamed to share it, but share it, I must.

Set your rice cooking in the rice cooker, and forget about it for the rest of the recipe. You will not see the rice until the end, and it will not trouble you again. If you do not have a rice cooker, get a rice cooker. I cannot emphasise enough that a rice cooker is worth it. I spent, like, 20 euros on this one. It makes rice. The rice is always good. It does not create drama or headaches or messes. Rice cookers are worth it.

Anyway, heat some oil in a pan. Dice your onion into however small pieces you feel like, then toss it into your heated oil. While it’s cooking, mince two cloves of garlic, trying the internet technique of pressing on them to get them out of their little shells. It’s finally started working for me, what about for you? If you’re using fresh ginger, chop and peel that as well, but I did not use fresh ginger, so I instead just popped open my jarred ginger and tipped some of that in. One note of caution here if you’re using jarred ginger - my jarred ginger comes in a jar that’s roughly the same size as a baby food jar, and its contents are roughly the same consistency as baby food. Do not confuse baby food for ginger. There are no scenarios in which that works out.

Add your garlic and dangerous ginger in with your onion, making sure to step back from the popping oil if using the ginger puree. While that’s hissing and spitting like a feral cat, dice your tomatoes and pepper, then add those to the mix.

Next is the trickiest step. Measure out one cup of peanut butter without making a sticky mess all over everything. It’s tough, right? As an alternative, you could just dump half a jar of peanut butter into the stew, which is probably what I should have done, but I was trying to develop the recipe, so I was at least going to try to measure things. Add your messy peanut butter to the vegetables, and stir to coat everything. Then, in an act of frustration, add your spinach, and once again, stir to coat everything. Could this have been done in one step? Possibly. Will it be? That’s up to you.

Once you’ve made a peanut butter-y mess in your pan, cook until the spinach reduces and looks less like an entire spinach plant took over your frying pan, and more like it’s creating a new, blended cultural experience with the rest of the vegetables in the pan. You want a happy community of vegetables, or at least, not a pure, raw spinach fest.

Once the spinach is mostly reduced, add your vegetable broth and spicy spices. Stir once again, and cook until the liquid mostly evaporates.

Once the liquid evaporates, return to your prodigal rice. Serve the kizaka on the rice. Or beside the rice. Or without the rice. Bom apetite!

Substitutions and suggestions

For the spinach: This dish is extremely flexible in what kind of greens it’s made with. Traditionally, kizaka is made with cassava leaves, but I couldn’t find them. If you can find them and want to give them a try, go for it! Do let me know how it goes! If making this with greens other than spinach, be sure to boil them first to get them tender before tossing them into the pan. Feel free to try with kale, collard greens, or whatever else you have lying around.

For the rice: Much like with last week’s Andorran recipe, you’ll find I’m a bit of a stickler for different types of rice, and don’t generally just accept “rice” as an ingredient. It’s like saying “mushroom” or “vegetable.” There has to be more to it than that! For this particular recipe, I used a sweet black rice, which worked as a nice counter-balance to the spiciness of the chili powder and red pepper flakes. You could use a regular white rice as well, but I’d probably stay away from the the shorter grain rices. If you are not a rice stickler like me, the regular white rice from the rice section at the grocery store will be fine, but do give black rice a try if you ever see it. It goes well with greens.

For the peanut butter: Traditionally, this dish is made with ground peanut powder instead of peanut butter; however, I could not be bothered to grind peanuts. I used an unsweetened, smooth peanut butter for this, which was really nice. You can substitute in whichever peanut butter you like, or even the peanut powder if you feel so inclined. I do recommend staying away from the sweetened stuff for flavour reasons, and chunky peanut butter on principle.

For the chili powder and red pepper flakes: These are completely optional. If you’re not a fan of spicy, I don’t recommend adding these. If you are a fan of spicy, add however much brings you joy.

For the vegetable broth: If you have leftover mushroom broth from last week’s recipe, that would definitely fit here as well. Alternatively, you can use water.

For the rice cooker: Hear me out. I was once a young, dumb college student, embarking on my adventures living on my own, and determined to cook for myself. I had a book of vegan stir fry recipes that promised to be simple and easy to follow, and I did my best. I’d dice my onions, slice my peppers, puzzle over tofu, all those marvelous things, but every time, I’d stare with dread at the words “serve with rice.” I’d look at my tiny pot and its bent lid, and I’d stare again at the words, deciding if it was worth the effort. I knew the headache that awaited me, of measuring rice and water, of monitoring heat, of wondering if the rice would actually cook like it was supposed to, or if I’d ruin my stir fry with crunchy chunks. I would try, and I would fail to make rice, and it broke my heart every time. I gave up on rice, and with it, my dreams of culinary greatness.

Until, years later, I moved to South Korea. My flat there came with a magical device, something I had beheld only in my dreams, believed to be the height of luxury, but which I now realised could be mine. There, on a small shelf, sat a rice cooker. It had a timer. It sang when the rice was ready. It was decorated with pink flowers, and made rice by the bucket.

I loved that rice cooker. It changed my life. No longer would I be in doubt about whether my rice would survive the cooking process. No longer did I need to look upon my bent and battered pot with concern. I would have perfect rice every time, when I wanted it, and without issue. I was in love, and it was all thanks to that rice cooker.

The moral of the story is to buy yourself a damn rice cooker if you make rice with any kind of regularity. It doesn’t even have to sing. It’ll just sit there and make drama-free rice for you. It will be way better than stovetop rice, and perhaps, you too will experience the absolute joy of well-cooked rice.

You can also substitute the rice for funge, an Angolan porridge made by whisking cassava flower in hot water. That’s also a way to get around chunky rice.

What I changed to make it vegan

Kizaka is traditionally served with fish, shrimp, or prawns. The process of vegan-ifying this recipe was deeply complex, with me deciding to… just not add those. Truly I am a culinary genius.

A brief context for this food

Angolan cuisine - and kizaka in particular - is a fascinating case study in how colonialism manifests in food. Angolan cuisine as a whole features many traditional west African elements, such as rice, beans, greens, and tubers, while also including elements that reflect its location on the coast, such as seafood. However, these elements have become blended with elements of Portuguese cuisine, such as the heavy use of olive oil and a greater emphasis on hot sauces. This combination of west African and Portuguese elements have also incorporated ingredients from throughout the Portuguese colonial empire. Cassava leaves, the greens this recipe is supposed to be made with, are not native to Africa, nor are the tomatoes which give the dish a broader character. These are imports from Brazil, a physical reminder of how interconnected colonial empires were, and the impact colonisers had on indigenous populations.

Understanding the context of kizaka requires understanding the history of the cassava plant, and how a plant from Brazil came to be a staple food in not only Angolan cuisine, but throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Cassava was first domesticated in western Brazil roughly ten thousand years ago. With its high nutritional value and resilience against pests and blights, it rapidly spread along ancient American trade routes, appearing in Mesoamerica by 4600 BCE. It appears frequently in Meso and South American art, and by Columbus’ arrival in 1492, was grown extensively throughout South America, Mesoamerica, and the Caribbean. European explorers were initially reluctant to eat anything made from cassava, but, upon realising how well cassava kept in ships’ holds, began to provision their ships with large quantities of it as they travelled from the Americas.

One consequence of this provisioning was the transportation of the cassava plant itself into areas colonised by the Spanish and Portuguese. By the 16th century, cassava had been introduced to Portuguese colonies in Africa - including Angola - as well as to Portuguese colonies in India and Indonesia. The plant thrived and spread, becoming a staple food throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Cassava is, then, a fundamental part of the history of colonial and post-colonial sub-Saharan Africa. It is an indelible product of that colonialism, one that has now been incorporated as part of the identity of the peoples that exist in its wake.

Kizaka, however, is older than the colonial history of Angola, and older than the introduction of cassava to Angola. Kizaka originates in northern Angola with the Congo people. There, it appears as a stew of mixed ground and boiled greens, cooked with palm oil, onions, garlic, and peanuts, and served at family gatherings. Like many traditional foods, I couldn’t find a definite source on the origin of this particular dish, but the ingredients that comprise that original Congo conceptualisation of it are thousands of years old. Onions and garlic likely originate from central or western Asia, and were likely cultivated around 5000 BCE. These likely travelled along trade routes into Africa, though their exact history is more difficult to trace than cassava’s. I also could not find what greens kizaka was likely made with prior to the introduction of cassava, as there are hundreds of edible plants throughout northern Angola. It’s possible there is no one particular plant that served as the basis for kizaka, or that that plant has been driven out by the introduction of cassava - if there is a way to know, I don’t have it.

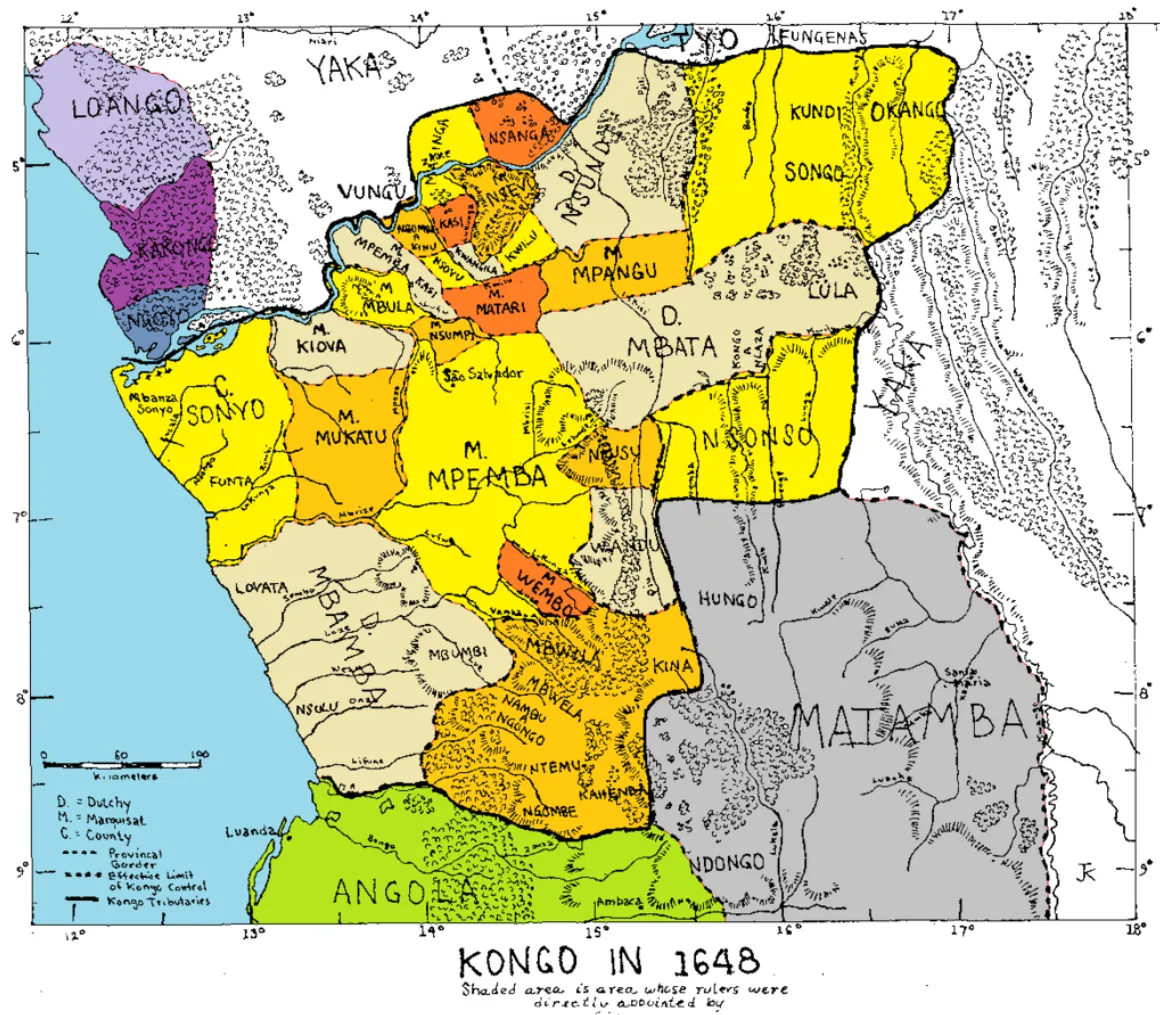

What we do know is why cassava has come to be a fundamental part of kizaka. The Portuguese began their colonisation efforts in Angola in 1575, founding the fort city of Luanda as a trade outpost, and trying to curry their guns and support with two nearby kingdoms, Ndongo and Kongo. After clashes with both, the Portuguese colony of Luanda exported goods and slaves from both kingdoms to Europe and the rest of the empire. The rising influence of Brazil led to trade directly with Brazil, and the introduction of the cassava in the 17th century. The plant followed the trade routes established with the Portuguese into Ndongo and Kongo, becoming part of the agricultural landscape of both kingdoms, as well as the myriad of other kingdoms in the region.

The increasing importance of Brazil, however, also meant an increasing need for slaves throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. While the Portuguese had originally been interested in trading for a wide range of goods with Kongo, their focus eventually narrowed until the trade was more or less exclusively for slaves. While Kongo had initially been able to meet Portuguese demand, the rising demand coupled with the increased cost of Kongo’s wars and internal tensions meant that, by the early 17th century, Kongolese rulers were dependent on European support to quell internal rebellions and unrest. This created a vicious cycle. Europeans would only accept payment in the form of slaves, but Kongo was too destabilised to fight an external war. To obtain slaves, then, Kongolese rulers became increasingly authoritarian, enslaving their own citizens for increasingly minute crimes, or no crime at all, leading to greater unrest. By the end of the 17th century, Kongo had become embroiled in civil war.

However, the Kingdom of Kongo would not cease to exist until 1914. Though much diminished, Kongolese rulers adroitly adapted to their changing political landscape. Kongolese people converted to Christianity and spoke Portuguese alongside Kikongo. Kongolese leaders established themselves within the European political landscape, using European powers such as the Portuguese and Dutch against each other to achieve their political goals. It was not until a failed war against the Portuguese occupiers in 1914 that Kongo ceased to exist, and even then, its monarchy persisted until 1965.

The story of Kongo is not unique in the grand narrative of European colonialism. Colonised peoples recognised colonisers not only as adversaries, but as opportunities to advance their own interests. Kongo is not the only African kingdom to have persisted into the 20th century. Many did, and they continued to be a force to be reckoned with for both one another, and for the Europeans who tried and failed to subjugate them. The story of colonialism is not a story of Europeans arriving and the world bowing down to meet them. It is the story of people meeting, clashing, trading, and using each other for their own ends. It is the story of traditions melding into something new that reflects the changing nature of the world. This story is sometimes erased under the artificiality of borders and nations, but the history of places is the history of its people, and this history of the Kongo people is one of adaptation.

Kizaka is a reflection of that colonial story. When made with cassava and tomatoes, it is a dish that could only exist in a post-Columbian Exchange world. Its presence throughout Angola reflects the impact of European colonisation and the eventual dissolution of the kingdom that originated it in favour of a new nation. It also reflects the nature of colonialism itself and the resilience of people and cultures. Kizaka as it was served prior to trade with the Portuguese likely no longer exists, but the dish as a whole does. It, like the Kongo people and Angola as a whole, changed and adapted, and took on elements of the coloniser that it wanted to take on. It adopted the cassava and tomato, and made them part of itself and its identity.

It is a blended dish, reflecting the rich history of Angola, and continuing the narrative of identity.