A longer and more detailed description

Look. I’m well aware of how literally every bread project I try goes. I know this is an exercise in failure, but equally, I know that, unless I try, I will never improve. And, I mean, it’s bread. People have been making bread in kitchens much less fancy than mine for thousands of years. How hard can it be? Surely I am worthy of the bread gods’ favour.

Surely?

As with all breads, we’ll start this one well before we actually want bread, but close enough to the bread time that we can stare it and think about the yummy thing it’s supposed to be. Put all your dry things in a bowl, then add the water and mix. Leave that in a warm place overnight, and dream of bread.

Wake up. Get dressed. Let your nice dream linger, or shoo your bad dream into the aether, for it is once again bread time.

Heat a lightly oiled pan over medium heat. Check on your batter, and hopefully, it’s risen. If it hasn’t risen, this will be a fun adventure. Add your batter to the pan, pouring in a clockwise motion to get a nice spiral, then fry until the batter is nice and bubbly. Flip it, fry for a moment longer, then repeat the process until you have replaced your bowl of batter with a plate of bread. Serve with olive oil and sesame (if you’re fancy) or honey (if you’re me). Bismillayso!

Suggestions and Substitutions

For the millet flour: Millet flour is the traditional flour used to make laxoox and its cousins throughout east Africa, but can be difficult to find. It unfortunately can’t be replaced with ordinary flour, but can be replaced with buckwheat or amaranth flour.

For the honey: I’ll repeat what I previously said about honey. Feel free to substitute whatever brings you joy.

What I changed to make it vegan

The base recipe is naturally vegan! The only thing that needs to be changed is honey, and then, that depends on how you feel about honey.

What to listen to while you cook

Djibouti is an exceedingly small country. It has a total population of less than the city I currently live in, and doesn’t have the best developed infrastructure. Its state-owned radio station, however, does have its own in-house band, and they’re quite enjoyable.

A bit more context for this dish

We’ve made some ancient recipes in this series, where I’ve talked about a dish likely stretching back to however long people have been in a given area. The same is true of today’s dish with the difference being the sheer amount of time people have been in Djibouti.

Djibouti, after all, lies solidly in the cradle of humanity. Hominid fossils dating back three million years have been found in Djibouti. Tools 1.5 million years old were found in the remains of a fossilised elephant. Djibouti and the rest of the Horn of Africa are likely the home of the oldest language family, with Afro-Asiatic languages being spoken here for at least 20000 years. There is old, and then there is the old that is East Africa.

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr)

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr)

Like most traditional foods, the history of laxoox is difficult to trace. We know breads have been made in the area since at least the 4th century CE due to the Greek scientist Oribasius creating an exhaustive list of Near East breads and their dietary value. The method by which laxoox is made has been found in the historical record since at least the 5th century CE, even if the first explicit reference to laxoox doesn’t appear until the 10th century CE.

However, there are a few elements of the story of laxoox that do make it somewhat easier to trace, and it goes back to the rock art I showed earlier in the article.

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr)

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr)

Djibouti is one of the hottest and driest countries on the planet. With an average annual temperature of 83.8F (28.5C)(“Quite pleasant” in Janneke), it consistently struggles with water and arable land. This limits what can be grown or harvested, with nomadic pastoralism having been common prior to French colonisation.

However, as the rock art shows, Djibouti’s current climate is far from the only climate it has ever had. The rock art at Abourma depicts ostriches, antelopes, and giraffes, creatures that cannot live in a desert. They provide a direct window on the past, and on the effects of climate change.

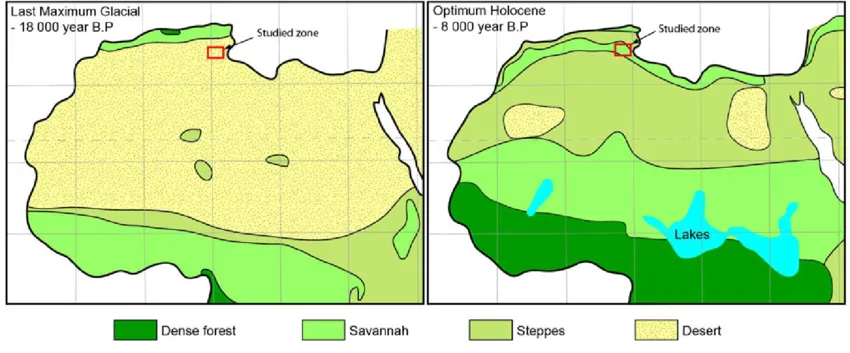

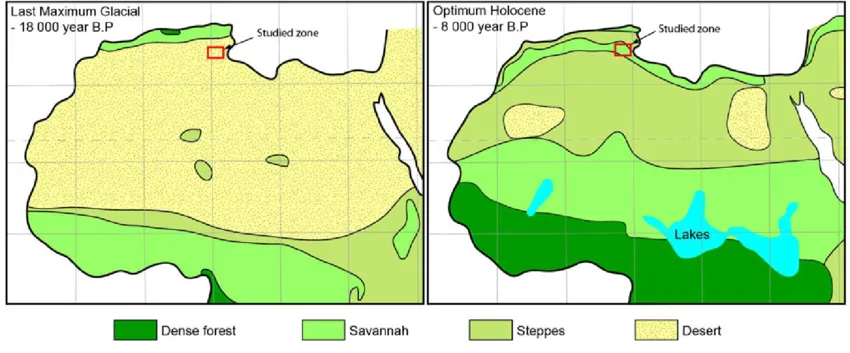

Source: Growth-strata geometry in fault-propagation folds: A case study from the Gafsa basin, southern Tunisian Atlas

Source: Growth-strata geometry in fault-propagation folds: A case study from the Gafsa basin, southern Tunisian Atlas

Humanity evolved in a relatively stable climactic point in Earth’s history. Throughout much of human evolution, what we now know as the Sahara Desert was not a desert, but fluctuated between a lush rainforest, vast grasslands, and occasional desert. This same pattern held true for the horn of Africa, with Djibouti being defined not by scorching desert, but grasslands. While this occasionally shifted into drier conditions - with those dry spells sometimes leading to migration out of Africa and into the rest of the world - the climate also generally reset back into grasslands and sometimes forests.

However, pollen studies have suggested that, starting roughly 6000 years ago, this pattern of gentle undulation between wet and less wet shifted, turning into an aridification of the region. Lakes dried up, animals moved on, and the people living in what is now Djibouti shifted to a pastoral lifestyle, herding animals from one feeding ground to the next. The grasses that remained were the grasses that could survive a rapidly drying environment, and they were few and far between.

They did, however, include millet.

Mary Apiding, a millet farmer in Uganda (Source: George Muron, via Monitor)

Mary Apiding, a millet farmer in Uganda (Source: George Muron, via Monitor)

Millet refers to a family of seeded grasses that are a staple crop across much of the hot, arid world, and one of the first crops domesticated as part of human agriculture. Finger millet - the species of millet common throughout east Africa - was likely first domesticated roughly 5000 years ago, and has continued to be a fundamental part of east African cuisine. Indeed, that’s part of why I recommended using millet flour for this recipe - anything else, and it’s doing a disservice to the literal thousands of years that this plant has been part of the human story.

If you’re looking at the timeline of millet domestication alongside the history of the aridification of Africa and seeing a pattern, you’re not wrong. Millet became and remains a staple crop because of its resilience in the face of drought. It is a tough little grass that will happily survive anything and remain edible on the other side. It is a fundamental part of the story of humanity. Much as any particular dish tells a story of a particular people or place, what the dish is made of is as much a part of that story. Millet is the grain that has kept places like Djibouti habitable, and is part of the fundamental fibre of the place.

It is also, of course, increasingly threatened by climate change as the entire region becomes hotter, drier, and more prone to drought. It is climate change that brought millet into the human story. It’s climate change that could remove it once again.

When we think about laxoox and how long it’s been part of the diet of the horn of Africa, it’s impossible to say with certainty. What is likely true, though, is that it has been part of the human story for centuries, if not millennia. As long as people have been eating millet, it seems not unreasonable to believe they’ve been grinding it up into flour and mixing it into something more interesting.

Making laxoox is diving not only into the very real and alive tradition of east Africa, but also a degree of our collective and shared past, one shaped by and continuing to be shaped by a planet warming faster than we can adapt to.

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr)

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr) 7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr)

7000 year old rock art at Abourma, Djibouti. (Source: Tony Karumba, via RFI.fr) Source: Growth-strata geometry in fault-propagation folds: A case study from the Gafsa basin, southern Tunisian Atlas

Source: Growth-strata geometry in fault-propagation folds: A case study from the Gafsa basin, southern Tunisian Atlas Mary Apiding, a millet farmer in Uganda (Source: George Muron, via Monitor)

Mary Apiding, a millet farmer in Uganda (Source: George Muron, via Monitor)