Chips Challenge

It’s interesting thinking about how games have evolved. I discussed this a bit in both my Beyond Good and Evil and Beneath a Steel Sky reviews, but it’s worth discussing again with Chip’s Challenge. With Chip’s Challenge, it’s interesting to think about not only how games have evolved, but how they _haven ‘t _ , and why that might be.

Now I’m imagining playing Chip’s Challenge as a roguelike, and I am afraid.

Now I’m imagining playing Chip’s Challenge as a roguelike, and I am afraid.

Chip’s Challenge is a puzzle game. You play as Chip, whose goal is to solve Melinda’s various puzzles so he can join her clubhouse. The puzzles increase in difficulty as Chip navigates through them, creating a constant sense of escalation and excitement.

The game is from 1989, and in many ways, very much shows its age. The controls are simple movement, with that movement being used to push blocks and interact with the world. There is no sprint or pulling, just pushing blocks and moving at a leisurely pace through puzzles.

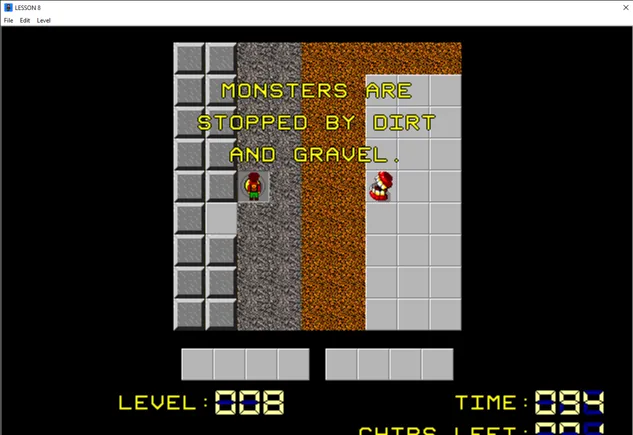

/immediately scatters dirt and gravel everywhere

/immediately scatters dirt and gravel everywhere

Of all the older games I’ve played in this series, it’s the puzzle games that have aged the best. Puzzles themselves are timeless things - what’s puzzling nearly 40 years ago is likely still puzzling today, and that is very true of the various levels of Chip’s Challenge. The basis of the game is in solving its puzzles, and those are still both compelling and satisfying. Equally, when a game relies solely on the strength of its puzzles rather than its graphics or story to convince the player to play, it shows its age less. In some ways, Chip’s Challenge isn’t too distinguishable from a more modern indie game like DROD or Baba is You . The design and mechanics are a bit different, but the underlying goal is the same - solve the room.

As a result, there were very few of the modern quality of life improvements that have been made to games that I was missing. Chip’s Challenge was still very playable, and there was still a lot of joy and satisfaction to be derived from it. That said, when playing Chip’s Challenge, its lack of forgiveness remained a constant reminder that this is an older game. There are no checkpoints within levels, no autosaves to fall back on as the level is solved. The level is either solved as a complete unit, or not at all. In some ways, this reminded me of speed running, and the utter lack of forgiveness any particular speedrun has for its player.

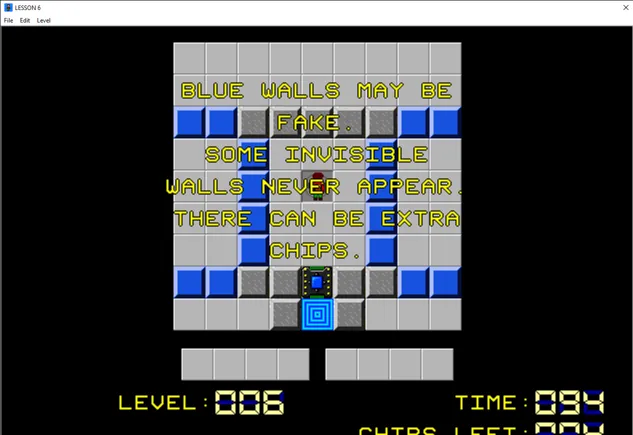

Mmmm…extra chips…

Mmmm…extra chips…

I’m not much of a speedrunner - I play on touchpad, and my fingers love gravitating to the wrong buttons - but there are a few games I can decently speedrun. I’m not bad at Geoguessr, and I’ve been preparing a speedrun of one of the games I’ll be reviewing later in this series. In both cases, speedrunning is entirely about movement memorisation and muscle memory, knowing where to click and what to press before you ever get there. It’s an entirely different skillset from actually playing the game, but still one that requires absolute mastery.

Chip’s Challenge is not a game I attempted to speedrun, but it was one that required that same precision of movement, and which had no forgiveness for my various slippages. Multiple times, I would make a wrong movement and find myself with no choice but to restart the level. Ordinarily, that would be frustrating, but here, while I noticed the lack of autosave, the levels were also short enough that I could sigh and dive back in. It’s the sign of a well-designed game when the process of needing to try again is not an act of tedium, but one of optimism, that this time, I might succeed, that this time, I know enough to actually make it through.

I don’t trust that bandit.

I don’t trust that bandit.

There are quality of life elements Chip’s Challenge is missing. I wish it had an autosave, and even though I approached each new level attempt with a sense of optimism, it might have been nice to not have to restart the entire level when I made a small mistake. However, the strength of Chip’s Challenge is not and never has been its game elements. Instead, Chip’s Challenge is the ur-example of how to design a puzzle game. Its puzzles are timeless and still challenging, and it’s in them that the strength and fun of the game lie. I had an excellent time noodling through puzzles. They don’t need high graphics or complex mechanics. Sometimes, just being presented with a room and a goal is all that’s needed.

Developer: Epyx

Genre: Puzzle

Year: 1989

Country: United States

Language: English

Play Time: 40-50 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/BmebmpeOnw8