Beneath A Steel Sky

Many of the games I play are fairly recent games, at least for certain definitions of “recent.” I rarely buy games on release day, but my library is chock-full of games from the 2010s and 2020s. Even those these are primarily indie games, they still reflect a certain modern philosophy of gaming and modern ideas of what a game needs to do or needs to accomplish to be successful. Even in that swath of time, though, I can already see some of the evolution of games. Games from the early 2010s don’t have the same ethos as later games, and are even further from games from the early 2000s. It becomes endlessly fascinating, then, when I find a game in my library from an even more bygone era. The goals and the ethos of the game are entirely different, and potentially no longer possible in modern gaming.

Point and clicks: The genre that is guaranteed to make me yell at my screen at least once a playthrough

Point and clicks: The genre that is guaranteed to make me yell at my screen at least once a playthrough

Beneath a Steel Sky is from 1994, and like many games from the 90s, it is a point and click. You play as Foster, a man kidnapped from his tribe and brought to Union City for mysterious reasons. There, he and his robot friend, Joey, struggle to find a way to escape the city, all while discovering what lies at its dystopian heart.

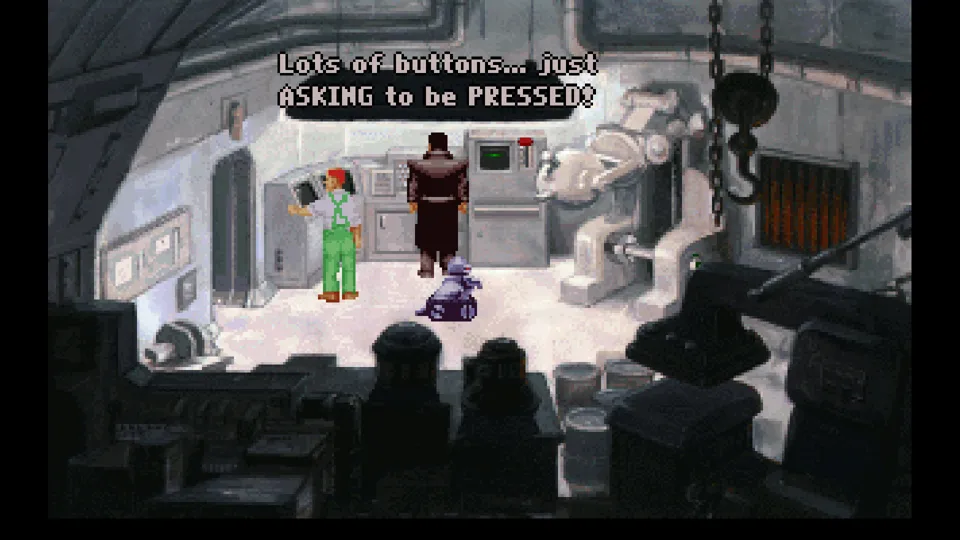

Like most point and clicks, the player progresses by finding items, using them appropriately, and moving from one space to the next. However, unlike many games in its genre, Beneath a Steel Sky’s use of this mechanic is refreshingly straightforward and largely devoid of the moon logic that plagues most point and clicks. It left me to feel a little more free to enjoy the setting and the writing.

This man is not wise.

This man is not wise.

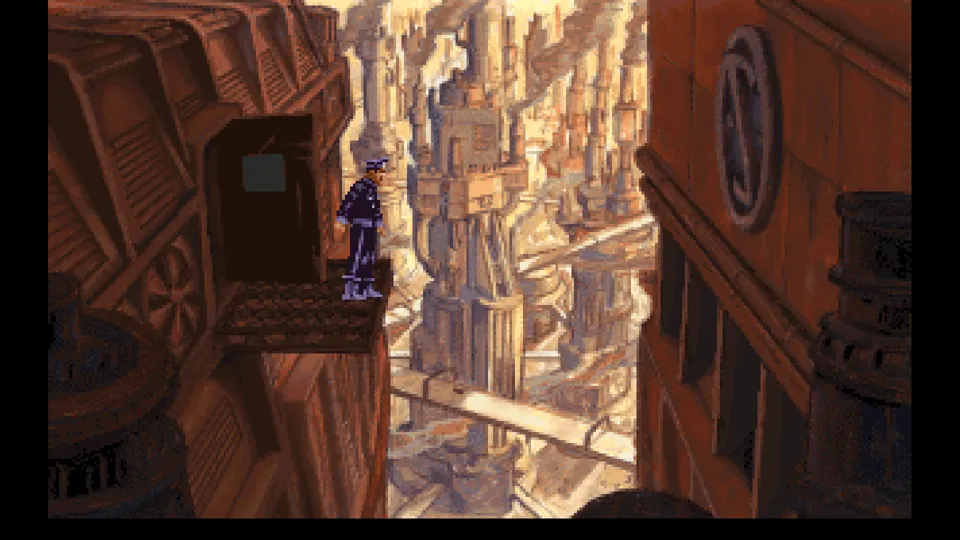

When I say Beneath a Steel Sky is from another age, I mean that not just in the sense of its graphics or its gameplay, though both are clearly from another era. The ideas that it has about what a game ought to be or what it ought to include are unlike any game I have played.

While its setting - a dystopian cyberpunk/rustpunk city - is not unique, the player’s interaction with it is unique. Beneath a Steel Sky approaches its setting with a combination of humour and reverence, recognising the fundamental horror of its broken world, and choosing to approach it, not with despair, but with jokes. Its double entendres and banter are fantastic, and create characters that feel both alive, and just as out of place in their world as any kidnapped person might be in a world that is not their own.

We’re kindred spirits, Foster and I.

We’re kindred spirits, Foster and I.

It’s this lightness that makes Beneath a Steel Sky so interesting to play, and what makes it feel like a product of its time. 1994 was an interesting time in media more generally. With the Cold War newly ended, and the War on Terror not yet begun, there was no truly global threat. The world felt optimistic, where the only threats were those we created for ourselves. Equally, much as with the end of the Cold War, there was no threat that could not be faced, no doom that could not thwarted. We were the arbiters of our own destiny, and we would use that power for good.

Beneath a Steel Sky reflects this mindset. As Foster explores the dystopia around him, it also becomes increasingly clear that it is a surmountable dystopia. It is one that, with the right person willing to take it on, could be undone, allowing a broken world to be made anew. As terrible as the world is, there is hope for it, and that hope can always be acted upon. There is a future in the bleakness, gleaming through and waiting for the right hero to seize it.

I’m playing this game in late 2023. The ethos of the mid 90s is not the ethos of the mid 2020s. That optimism in the world vanished with the advent of the War on Terror, and has been crushed into forgotten oblivion by the successive punches of economic crisis, societal disunity, the COVID pandemic, and climate change. We no longer live in a world when the apocalypse feels like a thing that can be thwarted, or the world that remains in its aftermath can be redeemed. We don’t live in that world that believes in redemption, just waiting to be grasped. We live in the world of Atom RPG , 20 Minute Metropolis , or As Far As The Eye , where the end is all around us, and we are scrambling just to try to survive. There is no redemption here, only the cruel, ever-advancing onset of the end of all we have ever known.

It’s this distinction in how we view the dystopia we inhabit that makes Beneath a Steel Sky so interesting. Its writing is stellar, and it’s just fun, but more than that, it paints a picture of a world I want to believe in. Setting the dystopia aside, it’s a world that has hope. It’s a world with a future. It’s a world with a happy ending, and where it’s okay to be enjoy that happy ending. It’s not our world, because we have given up on the idea that there is an escape from our dystopia. Beneath a Steel Sky is less from another time because of its graphics or gameplay, but because the philosophy that undergirds it is so beautifully optimistic that I had to stop and just stare.

It’s a thing of beauty, and I want it to stay that way forever.

Developer: Revolution Software

Genre: Point And Click

Year: 1994

Country: United Kingdom

Language: English

Play Time: 5-7 Hours

Youtube: https://youtu.be/QHkrlu83SM8