Depression Quest

I’ve talked about mental health - and my mental health specifically - in this series before. I’ve talked about how games’ depictions of mental health and the various ways our brains are structured can be helpful or hurtful. Hell, I’ve tried to capture what it is to exist in my head in my own writing . I understand what it is to try to capture that experience of being in a mental place that you know others aren’t in, and struggling to convey it. It’s as valid and important as any topic a game could centre around.

The question I’m left with is whether it works, and it’s there that I struggle.

Have you noticed I have, like, three major projects, besides being in law school? Distributing energy across projects is a fantastic way to not burn out on any one of them.

Have you noticed I have, like, three major projects, besides being in law school? Distributing energy across projects is a fantastic way to not burn out on any one of them.

Depression Quest is a narrative game following the story of an unnamed protagonist as they move through life with depression. The game presents its narrative through snapshots of the protagonist’s life, presenting the player with choices of how to respond to those situations, and changing the story depending on the choices they make. Throughout, the game provides updates on how depressed the protagonist is and how their life is going as the protagonist either improves or spirals deeper and deeper into depression.

I don’t hate this game. I need to preface this review by getting that out of the way. I recognise what the game is doing and why it’s an important thing for it to do. I know that there was and still is a significant amount of social stigma around depression, and that games like this one propel conversations about that stigma, eventually helping dispel it. My dislike of this game is not rooted in what it’s trying to do, or the validity of the project being undertaken here.

It’s in the assumptions that are made in the game’s very structure. It’s in how little the game does to truly capture what it is to have a differently structured brain in a world not meant for you. It’s in how we think about mental illness itself, and how that pathologising is portrayed in a game like this one.

lord my brain has never looked healthier

lord my brain has never looked healthier

I have never been diagnosed with depression. I do, however, have autism, and when both all the diagnostic criteria for depression and 14-40% comorbidity rates look familiar, I’m left with the sense that this game is not necessarily introducing me to something I don’t already have at least a passing familiarity with. The scenarios described in the game of not having the energy or spoons to handle a job, a relationship, side projects, and life, these are familiar. They’re familiar, not only to me, but to everyone I know. They are the scenarios that define life, that delicate balancing act of having limited time and energy with an infinite number of things all vying for that finite pool.

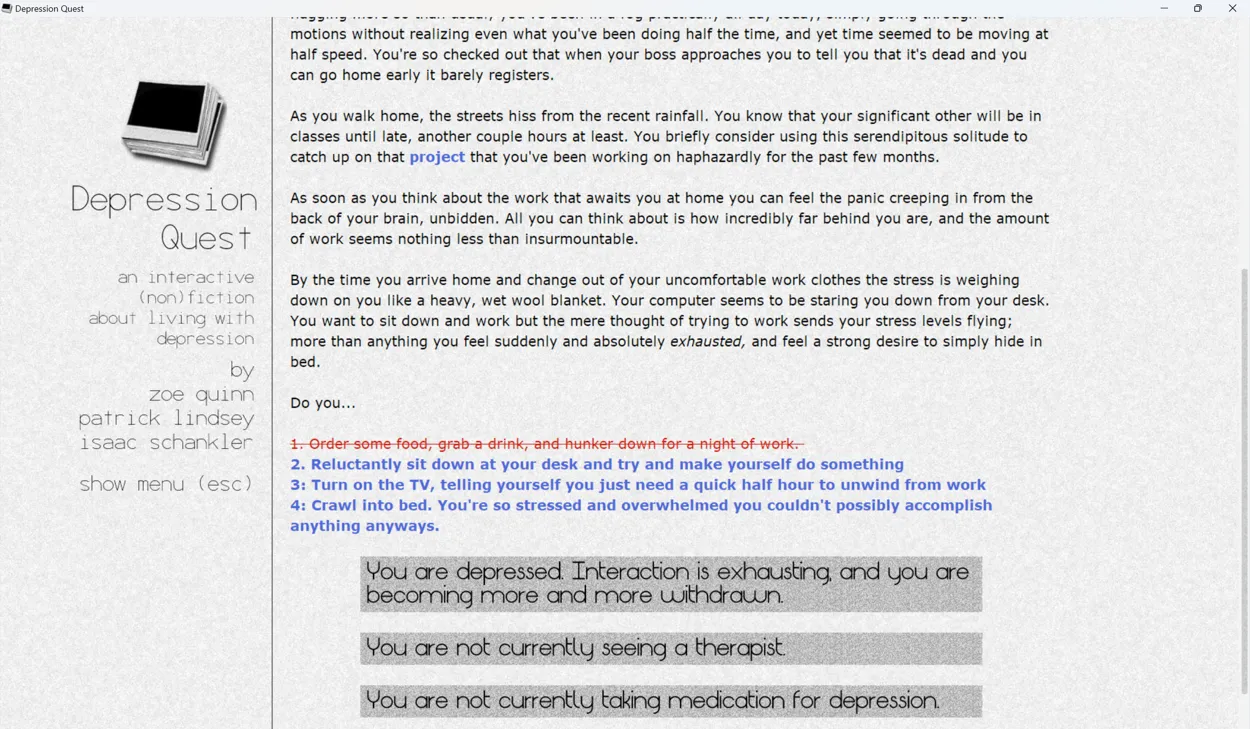

What makes Depression Quest centre a bit more on depression and a bit less on describing the human condition is its presentation of options. Each narrative comes with a list of choices the character could make, with each choice moving them somewhere along the depression scale. As depression progresses, more and more choices get blotted out, reflecting the increasing difficulty of basic functionality.

It is, of course, the player and their omniscient perspective who make the choice. We, the player, already know the correct choice, and there is no real incentive not to pick it. We know that the correct answer is to go to therapy, to talk to someone, to pet the cat. We know what we’re told to do to get out of the vicious spiral, and so we enact it here, with no real incentive not to do so. Picking all the correct answers leads to a happy ending, with the player being accepted and okay, as if the game is less a tour of depression, and more a primer on how to address it.

It’s that there’s a happy ending, a correct answer, a good outcome that sticks with me. I can’t let go of it. I know what the correct answers are because I’ve had this conversation so many times, and that there is a correct answer at all is endlessly infuriating.

Depression or ordinary introvert? Who can say!

Depression or ordinary introvert? Who can say!

In 1851, Samuel Cartwright coined the term ” drapetomania ” to describe what he saw as a psychological illness among enslaved persons attempting to escape slavery. In his view, slavery was the natural way the world worked. Attempting to rebel against the social order through escape was the sign of a fundamentally sick mind, and so, these enslaved persons must have had some sort of psychiatric disorder. While some - correctly - mocked Cartwright for the absurdity of thinking that wanting freedom from slavery was the sign of mental illness, drapetomania stayed in usage as a way to classify people who preferred roaming and living unsettled lives into the early 20th century.

Similarly, women’s bodies and emotions have been subjected to pathologising for centuries. Women not wanting children or behaving in “unwomanly” ways has been pathologised as the uterus “wandering” the body, demonic possession, or hysteria. A medical diagnosis and “medical” treatment was ascribed for what was ultimately a societal issue. If a woman did not want to or could not conform to what was expected of her, she must have been in some way sick, and therefore in need of treatment.

Medicine and what we see as illness is not purely objective. There is a sociological component, particularly with mental illness and what is and is not considered abnormal. That I have autism, and that it’s labelled as a disorder, for instance, is a decision based on societal norms and expectations. Why is it that I am the one with a disorder, and not a neurotypical person? Why is my brain and its functioning pathologised, and not yours?

This is absolutely not to say that depression is a purely societal disorder. There absolutely are physiological elements to depression that make it difficult for people with depression to function within society, and which can be treated with therapy and medication. Depression is absolutely real and absolutely a sickness that, if left untreated, can spiral, just like a physical one can. However, when a game like Depression Quest purports to provide a tour of depression, and also presents a set set of behaviours and activities that are normal and that a healthy person would be able to do, it creates a vision of depression that falls uncomfortably close to the examples of drapetomania and hysteria. What characterises Depression Quest’s vision of depression is not the experience of the sufferer, but their ability to function in a society that has chronically pathologised deviations from the norm.

A screenshot from Depression Quest

A screenshot from Depression Quest

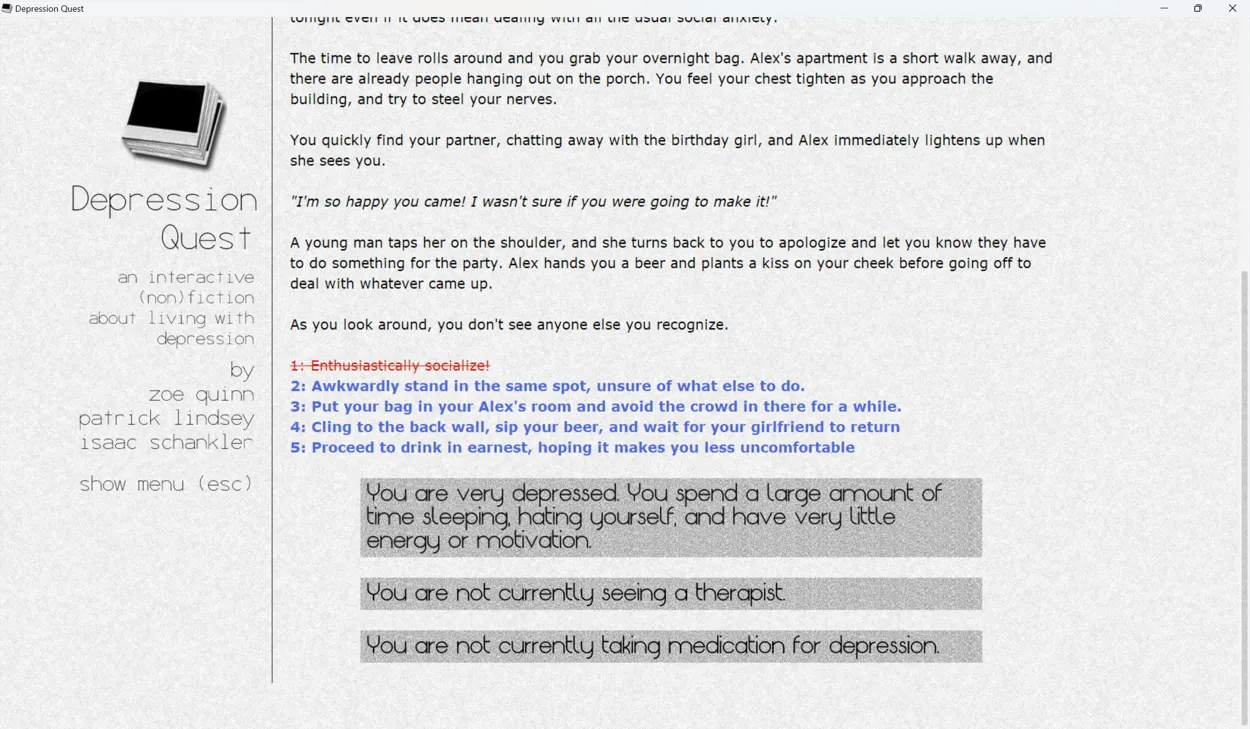

I am very, very far from being a paragon of mental health, but still, I don’t think that should limit me from being able to comment on this game’s presentation of healthy behaviour. Throughout the game, the player is presented with the option of talking to their family or partner about what’s going on, of going out to parties or nights out with friends, of opening up to acquaintances about their issues. The game presents talking to people and engaging with the world as the correct choice, with the decision to spend time alone, or to recuperate from the day as the incorrect choice.

That there are correct and incorrect choices reflects a particular way of seeing the world. When playing, I picked the correct answers because I knew what they were, and because I have spent my entire life having it drilled into me that the correct answer is always to go out and engage with people, attend the party, and choose to talk. I know what it is I’m supposed to do without consideration for what I’d prefer to do. When the game crosses out the “enthusiastically socialise” option at a party, it attributes to depression rather than to an active choice a person would make. The version of depression presented in Depression Quest is not the physiological illness that can be treated. It is the pathologising of introversion. It’s the treating of depression for the sake of engaging in what we’re supposed to do, not for its own sake.

This is where the game loses me.

A screenshot from Depression Quest

A screenshot from Depression Quest

I’m not going to pretend how I engage with the world is healthy. Equally, though, I’m not going to accept that the choices I make to not go out to bars or to have the majority of my social circle be online are signs that I am unwell and need treatment. Being exhausted after a day of drudgery is not illness - it’s a normal stress response. Feeling too tired after a day of work to do more work is not a sign of something wrong - it’s a reasonable physical response to productivity. My social life is not a sign of illness, but a sign of who I am and how I prefer to engage with the world. That that engagement is through text doesn’t make it less real or less meaningful to anyone involved. To claim that this preference is a sign of illness - as Depression Quest does - is to engage in exactly that pathologising that drapetomania and hysteria did. It’s to take a socially unacceptable behaviour and medicalise it, not for the sake of health, but for the sake of conformity.

The clearest possible example of this pathologising of normal behaviour is the COVID pandemic and people’s responses to the lockdowns. For millions of people, the prospect of being in the house, having to interact with the world digitally was a form of hell. It damaged a great many people, perhaps irrevocably, through isolation and the deprivation of that physical human connection.

I thrived.

For those brief few years, I got to live in a world that existed in the terms I needed. The ambiguities of face-to-face interactions vanished, replaced by the calculable, plannable medium of text. No one dropped by unexpectedly. No one expected me to go out. Everything became structured. My space remained perpetually my own. I knew what my days would look like, and what variations to expect.

A neurotypical world transformed into one built for autistic minds like mine. For once in my life, the world was built for me.

And I thrived. I became who I always could have been, and I did what I always could have done, had I had the space to do so.

Then the pandemic ended. And now I’m here, trapped in a world that I know can be built to accommodate someone like me, and which actively chooses to regard that accommodation with disdain.

When I’m stuck in a world that actively tosses away everything that made the world accessible for me, when I know the world can work for me, when the choice is made to rebuild having learned nothing, why would I not disengage? Why would I not retreat? The world has made it very clear that it can welcome me and chooses not to, so why should I go back?

A screenshot from Depression Quest

A screenshot from Depression Quest

When I ask the question about what we pathologise and why, it’s this disconnect between the possible and the real that I’m thinking of. I go back to that idea that the world is built in a certain way, to the exclusion of some, and then expects those some to medicate in order to conform. It’s this reality that Depression Quest captures and offers a guide to, not the actual reality that is depression.

Depression Quest is not a game for those with depression, despite it expressing it being based on the creator’s own experiences. It is the Hillbilly Elegy of depression games, presenting a palatable, sanitised view of mental illness that is digestible for the casual tourist, hoping to understand. It offers easy and safe explanations through correct answers that lead to the socially acceptable conclusion. Depression can be overcome, and its former sufferer be remade into a productive member of society, through the liberal application of therapy and drugs. There is no questioning of the underlying structures that might lead someone to this point, no thought to what it’s actually like to exist inside this mind. There’s just the correct path, and whether the sufferer chooses to take it.

Like Hillbilly Elegy, it has a near disdain for those who choose to deviate from the path, branding them as incorrigibly ill, regardless of who they actually are. It creates a universal from the narrative of a single person, and expects others to follow, discarding those who don’t.

There are ways to capture depression effectively, and to make the player truly understand what it is to exist within mental illness. The Beginner’s Guide is perhaps one of the best examples of this as it forces the player into the game creator’s mindset, having them see through his eyes and experience his thoughts. This type of storytelling effectively captures the confinement and anxiety the protagonist feels without moralising or making judgements about what is or is not the correct answer at any given moment. Instead, it allows the player to explore and understand for themselves. It’s show, as opposed to Depression Quest’s tell. It trusts the player, and so lands effectively.

Depression Quest doesn’t land. It progresses, and expects the player to follow, but the destination isn’t one worth reaching. Its portrayal of what a healthy life without depression looks like isn’t the paradise it believes it’s presenting. It is a hell of a different making, and I’m not interested in a manual of how to get there.

Developer: The Quinnspiracy

Genre: Interactive Fiction

Year: 2013

Country: United States

Language: English

Play Time: 30 Minutes

Youtube: https://youtu.be/PEC64FAu1KE