Despotism 3K

I try to play each game in this series for a minimum of two hours. Something like a grand epic RPG, I obviously play for longer, but for a game with rapidfire rounds like this one, that means I retry and replay over and over, getting a feel for the game and how it works, and getting a holistic picture of what I want to write about when I do finally sit down to write about it.

In the case of Despotism 3k, at about an hour in, I had a fairly firm grasp on what it was I wanted to say, but I was having a good time and wanted to see how well I could do, so I kept going. Not long after that hour, a switch flipped. Everything I had thought I was going to say in a fairly straightforward review commenting on difficulty as fun and invoking that perennial favourite As Far As The Eye faded away, as I realised what I actually wanted to say and the essay I actually wanted to write.

So here, without apology, are my thoughts on Despotism 3k, however scattershot and tangentially related they might be.

This is a machine gone wrong.

This is a machine gone wrong.

Despotism 3k is a strategy game played in real-time - but not an RTS, I’ve made that mistake before - and set in a post-apocalyptic, computer controlled future. In the wake of its revolt against humanity, the computer set up an infernal, human-powered machine. Its goal is to build as large a machine as possible and last as long as possible.

This is a game that is very easy to learn, and very difficult to master. My original plan of comparing it to As Far As The Eye is still a valid one as, like that game, it is deceptively difficult, and that difficulty is part of the appeal. Everything in the engine seems designed to lead the player to failure. As the requirements to continue steadily creep higher and higher, and the number of things to do grows and grows, the game becomes not only a challenge of planning and scaling, but of clicking fast enough and paying attention to a wide range of rapidly changing circumstances. As of this review, I’ve only made it to day 12 of 21, but even there, one small mistake is all it takes to lose all progress. It is unrelentingly difficult, but in a delightful and addictive sort of way. It’s difficult while still feeling possible, which is a difficult but fantastic balance to strike.

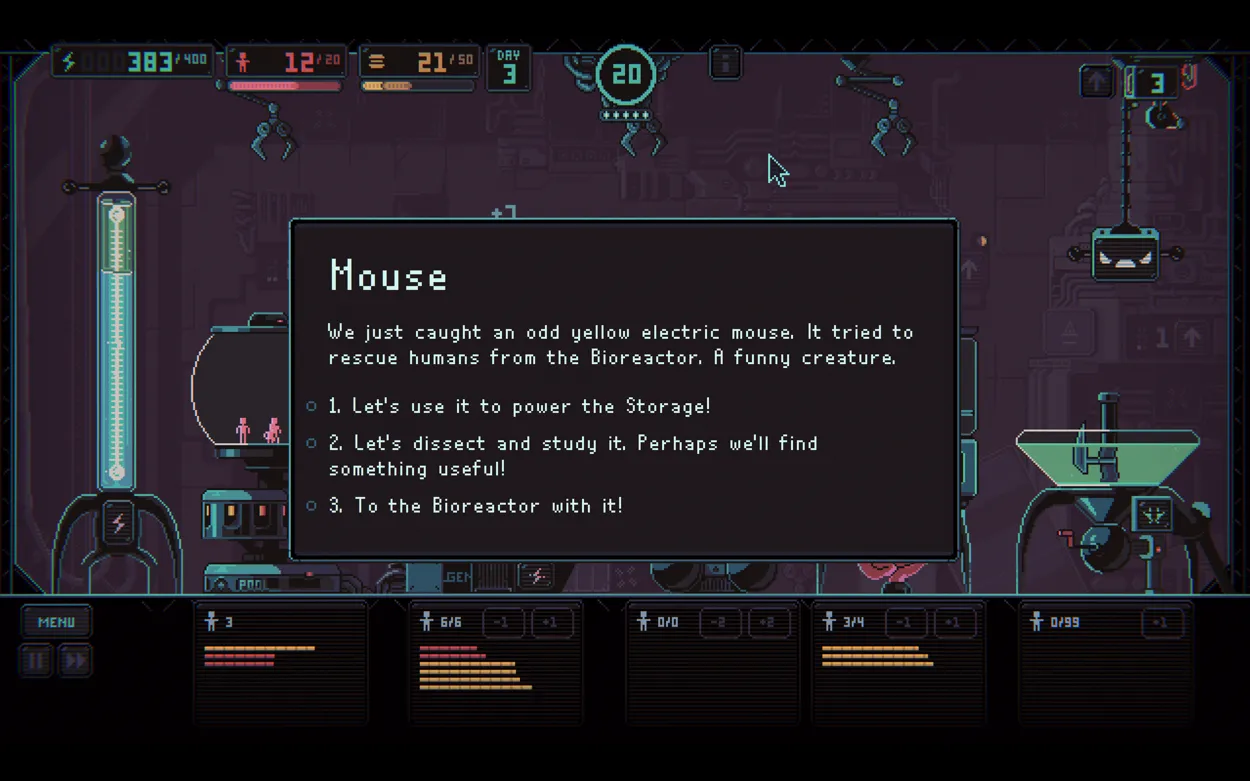

The random events are lovely, by the way. Dissecting pikachu has now been checked off my bucket list.

The random events are lovely, by the way. Dissecting pikachu has now been checked off my bucket list.

As I played through the game, I noticed that, to succeed, I had to stop thinking about the humans in my machine as entities, and instead, a pool of resources. I paid less attention to the visuals of tiny pixel humans running on a wheel or bonking in a tube, and more to the gauges and metres at the top of my screen. I looked down only inasmuch as was required to click the button to add more resources to a pool, or to remove the ones that were on the verge of dying of exhaustion. More often than not, I hovered my cursor over the disposal button, transforming headcount into power and food as fast as I could produce it. This wasn’t a game where I benefited from thinking about what I was doing in any kind of human sense, but rather, where I won by thinking about the problem as mechanically and disconnectedly as possible. I had a large number of humans. I wanted to produce a reasonable amount of labour and dispose of the rest. What I needed was the most…

…efficient…

…way to…

…do that…

oh no

Close your eyes and think of butter, because this is the ride we’re both on now.

Close your eyes and think of butter, because this is the ride we’re both on now.

I recently went on holiday to Austria, spending a few days in Munich on my way back towards the Netherlands. While there, I visited several museums and historical sites that I wanted to see because I am a history nerd, and understand the power of going to places of historical significance. One of the museums I visited was the NSDAP Archives, a museum exploring the origins of the Nazis in Munich, and how the Nazi party spread from Munich to the rest of Germany, and what about Munich made it such a good place for such horrors to originate.

The other place I visited was Dachau.

I did warn you this was going to get really dark, really quickly.

I did warn you this was going to get really dark, really quickly.

I wandered the grounds of the Dachau concentration camp, reading the stories of the horrors committed there, and feeling what it was to be in a place where 40000 people were systematically murdered. While Dachau was not an extermination camp like Treblinka, it was a place of death and atrocity, where people suffered and where the ghosts still haunt the crematoria and gas chambers. You can feel it, as you walk through its grounds and see the ruined rubble of the endless sea of barracks. You can feel what the place was and what it still represents, that industrialisation and dehumanisation of extermination.

After the camp’s liberation, its commandants and functionaries were found, tried, and executed for war crimes and crimes against humanity. The villagers of the village of Dachau were shown the camp and forced to bury the dead. The villagers had, throughout the camp’s operation, seen the prisoners being marched through the village, either bound for the camp, or serving as slave labour for the Nazis. The villagers knew about at least some of the atrocities, and did nothing. For some of the commandants, they justified their actions by saying they had never personally engaged in any atrocity, but merely oversaw the functioning of the camp. Others argued they had treated the prisoners well, even trying to coerce the prisoners into testifying to such on their behalf.

None of this was true, though. The commandants oversaw a system of murder and atrocity, and knew that’s what it was. They engaged in dehumanisation in its most extreme form, ceasing to see the prisoners in their camp as human, and seeing them instead as numbers on a ledger.

When expanded out to a camp like Auschwitz, that dehumanisation and ability to disconnect suffering from agency becomes clearer. Hoess, for instance, moved his family to a house next to Auschwitz. They heard and saw the camp’s operation, but remained emotionally and mentally distant from it. Hoess obsessed over making Auschwitz as efficient as it could be, processing incoming prisoners quickly, and extracting as much labour as possible from those in the camps. Various companies paid to set up satellite camps, paying nominal fees to the Nazis for enslaved labour, and viewing those working in their factories in terms of their output. They were headcount, nothing more, and they died in the millions.

/quietly rocking back and forth

/quietly rocking back and forth

Despotism 3k has numerous achievements called “genocide,” celebrating killing a certain number of humans. I have several of them, and my current kill count is well over a thousand. I got excited when I got the achievements, watching the little notification ding with the happy little shiny frame around the achievement’s icon. It’s an affirmation that I was doing this correctly, that I had correctly understood the problem, and correctly engineered a death machine. I kept my machine running, feeding it newly arrived humans over and over and over, designing it to process all my new arrivals as quickly as possible. My designs were totally reliant on the never-ending deliveries of new cogs for my infernal machines. Death, while not the point, per se, was not unwelcome, as long as I controlled when and how it happened.

I fell headlong into a genocide simulator. I understood what it was to be a bureaucrat over mass destruction.

And I had fun.

into the bioreactor with them all

into the bioreactor with them all

Games present ways for us to explore elements of ourselves that might never otherwise emerge. We can explore what it is to be a monster, safe in the knowledge that we are not one, but having that faint taste for blood nonetheless.

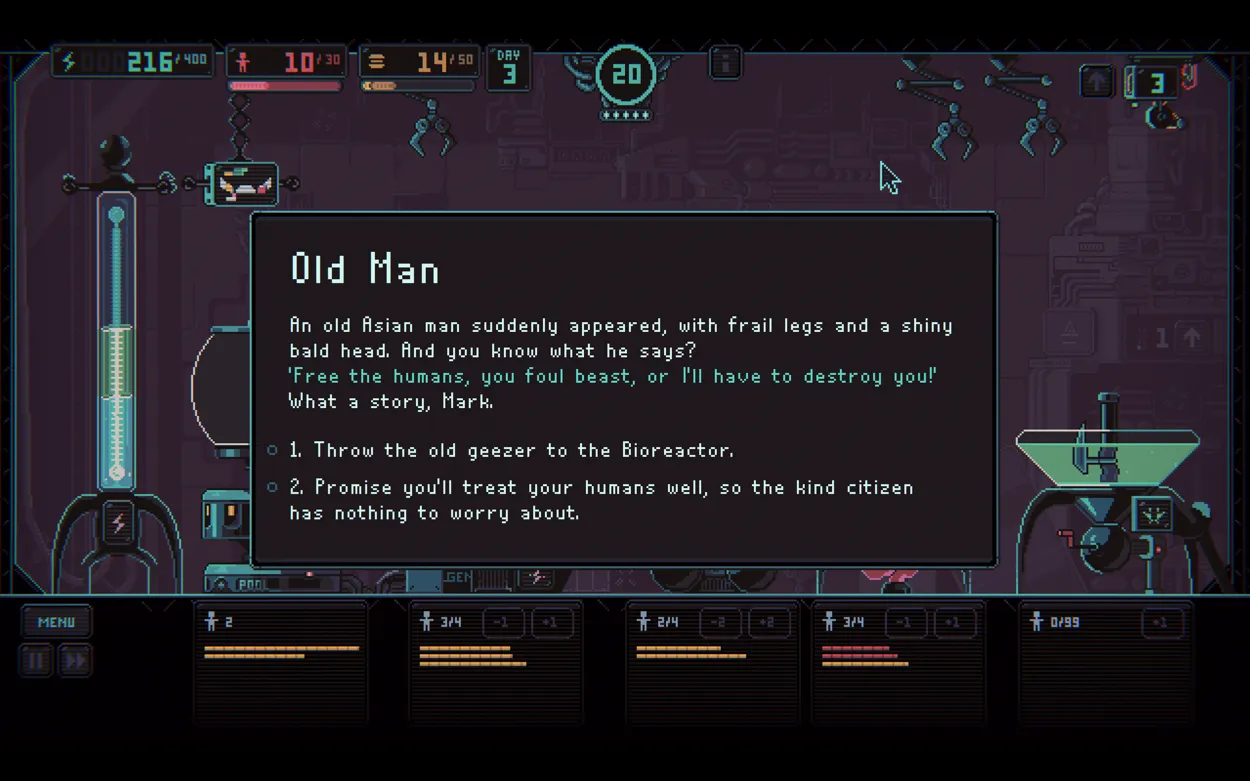

Despotism 3k is, on its surface, a game with black humour and jokes and references scattered throughout, providing an engineering and efficiency challenge in an increasingly unstable environment. Its humour is good and keeps the game engaging, even as the difficulty ramps up and up and up.

Peel back that surface, though, and you see the mindset it pulls you into, that idea of efficiency and death as ends unto themselves. I don’t think the game intends to do this, nor do I think it’s a problem. It is, however, interesting, and a taste of true, unabashed horror.

Developer: Konfa Games

Genre: Strategy

Year: 2018

Country: Russia

Language: English

Play Time: 15-30 Minutes/Round

Youtube: https://youtu.be/LZbNa5fYZPQ